Feature

FERRARI’S DIVINE DELIVERANCE: Remembering an emotional Monza 1-2 for the Scuderia

Share

The death of Enzo Ferrari brought an end to an extraordinary era, and could scarcely have come at a worse moment for his great team. But then an extraordinary sequence of events saw the Gods smile at Monza - and I was there to see it all unravel…

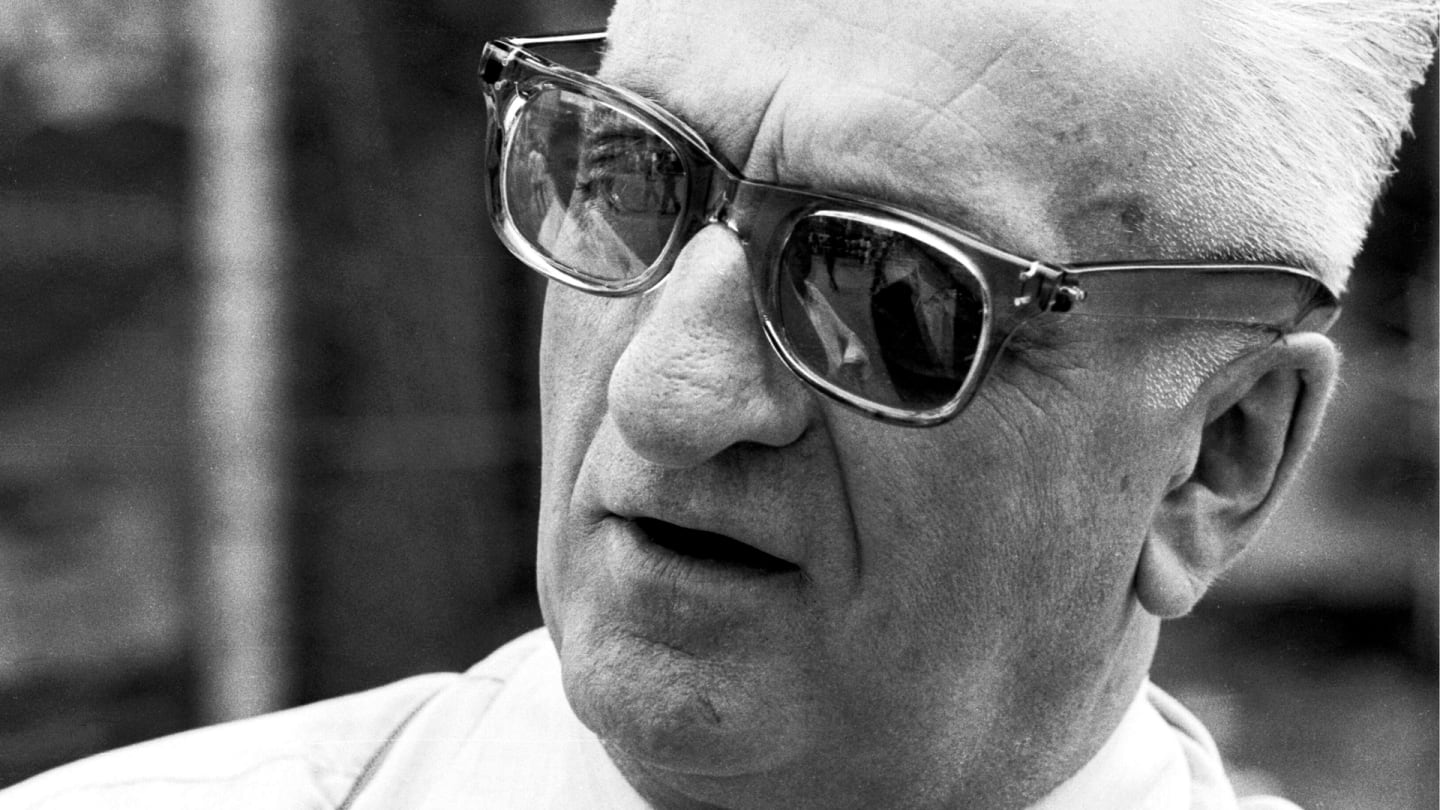

Enzo Ferrari - Il Commendatore, Il Drake - always seemed such an indestructible figure. With his flowing white hair and the inscrutability and air of mystery he deliberately cultivated with his trademark dark-lensed spectacles, he sat astride his empire, an imposing and intimidating autocrat. He never went to races, but would appear every so often on a practice day at Monza, to check up on what his lieutenants were doing.

When the end came on Sunday, August 14th, 1988, the founding father of Italy’s greatest racing team - many said the world’s - was a grand 90, and his passing represented an historic milestone and left a void that would never be filled.

It also added more pain to what had been a hugely trying season. Gerhard Berger had won the last two races of 1987 in the revised F187, but in the last season of the 1.5-litre turbo formula, when significant rule changes limited both horsepower and fuel allowance, Ferrari lost ground again. From 4-bar boost and 195 litres of fuel, the turbocharged cars were now limited to 2.5 bar and 150 litres.

Ferrari, like many others, merely warmed over their previous year’s design, as the F187 became the F187/F188. In some ways this made sense as John Barnard’s elegant 3.5-litre, normally-aspirated V12-powered 639 machine for 1989 took priority behind the scenes.

McLaren and Honda, however, had not warmed anything up. Steve Nichols’ lowline MP4/4 was an all-new design, allied to a heavily revised RA168E Honda V6, which had specifically been created to exploit the new rules to the maximum.

As political argument raged as a prelude to the season, and then as an ongoing backdrop - much of the politicking concerning Ferrari themselves even when the Old Man was alive - tensions in Maranello mounted and were then ramped up when it became clear that virtually nothing could stop the red and white McLaren steamroller.

Alain Prost won the opening round in Brazil; and then Ayrton Senna, freshly signed from Lotus, won the San Marino GP before crashing out spectacularly in Monaco while romping away from Prost, who was the beneficiary of his team mate’s momentary lapse at Portier.

Prost won again in Mexico before Senna hit back with a North American back-to-back in Montreal and Detroit. Prost won at home in France, then gave up with a serious misfire in the rain at Silverstone, where for the first time Ferrari had shaken McLaren in qualifying. As they struggled with new bodywork, Berger took pole. He led the race, too, before Senna, in an MP4/4 fitted with old bodywork, caught and passed him easily.

Senna won in Germany, Hungary and Belgium, too, so by the time of the Italian Grand Prix on September 11th, McLaren had won all 11 races.

Monza, however, did not go to the script. Of course, on such a fast track where horsepower was everything, the McLaren Hondas wrapped up the front row, with Senna ahead of Prost – 1m 25.974s to 1m 26.277s. The Honda RA168E produced around 650 bhp (well down on the 4-bar turbos of 1987), but Ferrari started the year with perhaps 620 and claimed around 640-650 by their home race. But Berger’s third place on the grid was won with a lap of 1m 26.654s, and team mate Michele Alboreto, in fourth, lapped in only 1m 26.988s.

Nevertheless, that left them well clear of the Megatron Arrows of Eddie Cheever (1m 27.660s) and Derek Warwick (1m 27.815s), Nelson Piquet’s hopeless Lotus-Honda on 1m 28.044s, and three fastest atmo cars, the Benetton Fords of Thierry Boutsen and Alessandro Nannini and Riccardo Patrese’s Williams Judd, with 1m 28.870s, 1m 28.958s and 1m 29.435s apiece.

Senna’s pole gave him a new record of 10 in one season, having previously shared nine with Niki Lauda, Ronnie Peterson and Nelson Piquet. But it was Prost who got the drop as they left the startline. But by the time they braked for the first chicane Senna muscled through and simply blasted into the distance, leaving astounded observers to ask, “Just how does he do that?”

The answer was easy. He was always brilliant on full tanks and tyres that weren’t fully warmed up. But there was another reason that day. Alain’s engine had started to misfire even as he upshifted to third, in a harbinger of what lay ahead.

In final qualifying all of the Honda runners had used experimental high-revving XE-3 variants of the RA168E, and as others reverted to the EX-2s for the race there were suspicions that Prost and Piquet’s team mate Satoru Nakajima had stayed with the later versions.

After 22 laps the McLarens were running 4.61s apart, easily outpacing Berger and Alboreto. By lap 28 Prost, who kept pushing despite his misfire, had reduced that to 2.54s, and rumours would later circulate that, realising that he was unlikely to finish the race, he was deliberately trying to push his unloved team mate into either doing likewise, or else running short of fuel. Even the Hondas were close to the edge on consumption at Monza that year.

Prost had duly lost a lot of ground when he finally had to quit on the 34th lap, and had been passed by Berger before his engine actually failed. It was suspected that running a lean fuel mixture for too long had been his downfall.

Now things didn’t look so rosy for McLaren. Indeed, they faced not just a dilemma but a potential crisis. Way out in the lead, Senna could afford to back off and richen his mixture at the expense of using more fuel. Except that he couldn’t ease back too much to try and conserve it, because Berger, who had been doing that once he realised he couldn’t keep pace with Prost, was suddenly pushing hard again and actually making inroads by the 40th of the 51 laps. Ferrari, meanwhile, were begging their drivers to back off.

Was Senna sandbagging? Did he have pace in hand? The answers were no and yes, but what he didn’t have was fuel in hand. Indeed, there had been rumours all season that the McLaren Hondas had often run a lot closer to the edge of their consumption than Ron Dennis and his men ever let on, such was the pace of their battling drivers. So now Ayrton was having to push as hard as he dared in the corners to eke out his fuel.

Going into lap 49, his lead had been cut from 30 to just four seconds.

Heading to the first chicane, he came up behind his friend and countryman Mauricio Gugelmin’s Leyton House March 881, and sportscar star Jean-Louis Schlesser’s Williams. The Frenchman, the nephew of Jo Schlesser - who had died in the 1968 French GP - was standing in for Nigel Mansell, who was sick.

Schlesser was fighting Gugelmin despite being lapped by him when he got out of shape, locked up and ran wide as Senna dived down the inside of him, believing that the Williams was in any case about to go off. But Schlesser somehow got the FW12 turned in. Senna was in the right-hand section of the chicane when Schlesser, two wheels still in the dirt, whacked the MP4/4’s right-hand sidepod with his left front wheel. Suddenly, Senna was spinning backwards over the kerb.

Nigel Roebuck and I had been watching from the media grandstand opposite the pits as the drama unfolded, and decided we had better leave on lap 49 to get back through the tunnel before the cops locked the paddock gates to keep the tifosi at bay after the race. As we were in the tunnel we heard a tremendous roar from the crowd, and as we emerged, there on the big screen was Ayrton, helplessly beached at the first chicane. McLaren’s supersonic challenge had augured into the desert.

Berger was leading! And Alboreto, struggling with his car jumping out of fourth, was second! The tifosi screamed themselves hoarse and invaded the track after the Austrian led the Italian home by 0.502s.

It was the first Italian Grand Prix to be held since Enzo Ferrari’s passing, three days short of a month previously. And the last Ferrari 1-2 at the autodromo had been achieved by Jody Scheckter and Gilles Villeneuve back in 1979, when all Gilles had to do was pass his team mate to keep his own title hopes alive, yet had been obliged, by team orders and his own code of honour, to ride shotgun instead.

There was a spiritual symmetry to it all. But it wasn’t quite the end of the story. Down at McLaren, Senna sat in the motorhome looking much calmer than one might have expected.

“Jean-Louis Schlesser is outside. He wants to talk,” somebody told him.

Senna looked up as the shamefaced 44 year-old F1 rookie shuffled in. Jean-Louis is a tough and very colourful fellow, and he’d been certain initially that he hadn’t been the responsible party. But now he wasn’t so sure, and was expecting some fireworks and wrath.

“I’m sorry, I’m so, so sorry,” he repeated over and again as Senna sat, emotionless as a sphinx and saying nothing until Jean-Louis stopped speaking. Then he accepted the apology with glacial equanimity.

Meanwhile, there was drama going on outside. The protocol back then was to measure the fuel cells of the top three cars after a race. I was there watching as Berger’s was refilled several times after the first attempt - and saw the Ferrari accept 151.5 litres when its maximum should have been 150.

Panic!

I remember that Bernie Ecclestone was there too, presumably because somebody was getting nervous. It took four goes before the reading said 149.650 litres, and there the matter rested.

Relief!

But even if it had not, and Berger had been disqualified for having too much fuel, Michele was there in second place to maintain the fairy tale ending. And for him that last great run was a slap in the face for Frank Williams and Patrick Head, who only days earlier had decided that they didn’t want him after all for 1989 despite shaking hands on the deal in Hungary. Second place and fastest lap proved a point for the man who would go to Tyrrell the next season and cause a stir in their dramatic new car.

Monza, of course, was a false dawn for Ferrari, and thereafter for McLaren it was business as usual. Prost struck back with back-to-back wins in Portugal and Spain, before Senna won the Japanese GP in difficult conditions to cement the first of his world championships.

Prost had actually scored 105 points to his 94, but under the arcane rules of the day drivers could only count a certain number of scores, which left them with 87 and 90 points respectively. Berger trailed with 41. And in the constructors’ stakes the gap was even greater. With 15 wins out of a possible 16, McLaren had 199 points to Ferrari’s 65…

Monza, motorsport’s cathedral of speed, is numinous. A place where you can so often sense the ghosts of its departed heroes. If McLaren had to stumble in their domination of the 1988 season, if some divine intervention had to interrupt their incredible flow, no venue could have been more apposite than Ferrari’s home ground.

It was quiet there that evening, as the delighted tifosi had left and the tumult and shouting had died, and the only movement in parts of the paddock seemed to be the litter that a light breeze blew long the ground, or the rustle of the trees.

But if you listened very hard, every now and then, you could believe that other sound you caught intermittently was that of an Old Man, laughing softly to himself.

WATCH: Senna tangle gifts Ferrari emotional one-two

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked Max vs McLaren (again) and Hamilton in the hunt – What To Watch For in the Spanish GP

News Verstappen admits Russell contact ‘shouldn’t have happened’ in Spanish GP as Dutch driver nears race ban threshold

Video WATCH: See how Piastri beat McLaren team mate Norris to pole with our ‘Ghost Car’ feature

Video WATCH: Verstappen collides with Russell in astounding moment during Spanish GP