)

Feature

‘He obliterated the opposition’ – remembering Senna’s first F1 win

Share

)

On a cold and wet Portuguese day in April 1985, Ayrton Senna scored the first of his 41 Grand Prix victories. With the unique insight of Steve Hallam, the man who engineered the Brazilian’s jet-black Lotus 97T at Estoril, we remember a drive of epic proportions…

“That race,” Renault driver Patrick Tambay said of the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix, “was a nightmare. It was p*ssing with rain from start to finish, very, very flooded everywhere, the cloud ceiling very low and the light very poor. It was survival of the fittest.”

And on that tempestuous April afternoon at Estoril, there was absolutely no doubting who the fittest member of the 26-strong F1 pack was...

While other drivers - including the likes of Alain Prost and Keke Rosberg - struggled simply to keep their cars pointing in the right direction, Ayrton Senna, driving in his second race for Lotus and only his 17th Grand Prix, put on a masterclass in wet-weather driving.

Portugal 1985 - Ayrton Senna's first F1 win

When the chequered flag came down after more than two hours of racing, the fresh-faced Brazilian had not only won the race by over a minute, led every lap and claimed fastest lap (to add to the maiden pole position he’d earned in dry conditions), he’d also made good on the extraordinary promise he’d shown a season earlier when as a rookie he finished a brilliant second for Toleman in similarly abysmal weather at Monaco.

“To win in those conditions takes an exceptional talent,” recalls Senna’s race engineer Steve Hallam today. “There were 20-odd exceptional talents out there that you could say failed miserably on that day - and he didn’t. He brought it home convincingly.”

The rain arrived in Estoril just ahead of the start, heaping pressure on the pole position debutant. If he made a good getaway Senna knew he’d have a clear road ahead; conversely a bad start would leave him engulfed in spray. As it happened the Brazilian did a superb job off the line, limiting his wheelspin to lead team mate Elio de Angelis (whom he’d out-qualified by a full second) into the first corner.

From then on Senna was very much in a race of his own.

“He did what all good racing drivers do - he looked for the grip,” says Hallam. “The grip in wet conditions isn’t always found on the dry line, so to speak. The tyres behave slightly differently. He was very good at adjusting his line, feeling the car and finding the grip. That, on a day when the rain was so heavy, coupled with the finesse that he had and was later to prove as a driver really obliterated everybody else.”

As the weather worsened, so Senna continued to extend his advantage up front, and with 30 laps gone and more than 30 seconds in hand it wasn’t long before Lotus designer Gerard Ducarouge suggested asking him to ease off.

“At the time you are always nervous, thinking ‘do we need to intervene in what he is doing’,” remembers Hallam. “But as we got to know him he explained that he used to get into a rhythm, and to actually ask him to slow down or adjust his pace in his view put him more at risk than letting him stay in that rhythm.

“He reminded me of that conversation after Monaco in ’88 [when Senna crashed out having been leading by more than 50s] where McLaren had asked him to ease and he had obeyed them and it just took him out of that rhythm or that zone that he had been in. He said to me later: ‘See - remember what I was telling you?’”

Niki Lauda would later say that conditions were ludicrously dangerous, and that the race should have been stopped much earlier

By lap 31 conditions had deteriorated to the point where Alain Prost, running third behind the other Lotus of De Angelis, lost his McLaren midway down the pit straight after aquaplaning through standing water. Senna too had issues, despite his obvious mastery of the conditions.

“After the race he said ‘I didn’t drive perfectly and there were one or two occasions when I thought I was going off’,” Hallam says. “On the back side of the circuit there was a fourth- or fifth-gear kink behind the pits and he said that he’d been completely sideways and thought he was going to throw it all away going through there on one or two occasions. But that was principally because of the volume of water on the track.”

Indeed McLaren’s Niki Lauda would later say that conditions were ludicrously dangerous, and that the race should have been stopped much earlier. Senna, too, had called for an early end to proceedings.

“I do remember him gesticulating to try to have the race stopped and I remember the cynics afterwards saying ‘remember last year? If they hadn’t stopped it early in Monaco he would have won’,” says Hallam. “But it is what it is and he won the race. He would be the first person to just let that pass.

“I think the conditions we raced in 30 years ago, without Safety Cars and what have you… there would probably have been lots of traipsing around behind the Safety Car at that event had it have been run nowadays, which in many respects highlights his capability even more.”

Before his untimely death in 1982, Lotus founder Colin Chapman was famed for celebrating his team’s victories by leaping onto the track and throwing his trademark cap into the air, so it seemed rather appropriate that when the chequered flag was brought out after 67 of the 69 scheduled laps, the Lotus mechanics, barely able to contain their joy, spilled over the pit wall and onto the track to celebrate with their new hero.

Mirroring their exuberance, Senna - who’d finished more than a minute ahead of Michele Alboreto’s second placed Ferrari having lapped the rest of the field - flung off his seat belts and all but climbed out of the cockpit as he raced down the pit straight, arms aloft.

When he returned to a soggy parc ferme several minutes later the elation hadn’t subsided a bit.

An emotional podium ceremony would follow – but despite the enormity of the occasion, there would be no partying into the night.

“One of the things that keeps the race high in my mind were the iconic pictures that were taken in parc ferme as he drove in,” says Hallam. “Most of the team were there and you can see the expressions of joy on people’s faces. There’s a great picture of [Lotus mechanic] Kenny Szymanski who actually looks like he’s pogoing because his feet are together but they’re 12 inches off the ground as Ayrton drives in.

“Ayrton has his arms out of the car and he’s waving to us, and then he gets out and hugs everybody. It was special.”

An emotional podium ceremony would follow, but despite the enormity of the occasion - not only was it Senna’s first victory, it was also just the second win Lotus had scored in six seasons - there would be no partying into the night.

“We were on a flight out that night," recalls Hallam. “It was one of those events where you wished you could stay and absorb what was going on, but it was bloody wet. The pack-up wasn’t fun - you just wanted everything put away into the truck and hope it was as dry as possible.

“We had arrived in Estoril from Brazil - the cars hadn’t been home. So it sounds a bit of an anti-climax, but that’s what it is when you go home the night of a race after you’ve won. We were just thinking about getting to the airport and getting home.”

Looking back now, Hallam, who worked with Senna for three seasons at Lotus before linking up with the Brazilian again at McLaren, recognises the importance of that first victory.

“It felt like the start of something, there’s no doubt about it,” he says. “I think Imola was the next race and he put the car on pole there. We were thinking ‘wow’.

“It wasn’t long before we were thinking ‘we’re the ones who are going to let him down - if we keep the car underneath him, he’ll keep bringing it home.’”

And for the next decade, come rain or shine, that’s exactly what Ayrton Senna did.

Estoril ‘85 in Senna’s own words

“It was a hard tactical race, corner by corner, lap by lap because conditions were changing all the time.

“The main thing was to keep concentration and get used to the wet track that we [hadn't had] for the whole weekend. So we were going through the race with a very slippery track. The car was sliding everywhere - it was very hard to keep the car under control. You often saw cars sliding about all over the place purely through lack of grip and too much power.

“Even if I had a good comfortable lead it was difficult to keep the concentration, to keep the car under control right to the end.”

“Once I nearly spun in front of the pits, like Prost, and I was lucky to stay on the road. People think I made no mistakes, but that’s not true - I’ve no idea how many times I went off! Once I had all four wheels on the grass, totally out of control, but the car came back on the circuit. Everyone said: ‘fantastic car control.’ It was just luck.

“People later said that my win in the wet at Donington in ’93 was my greatest performance - no way! I had traction control! Okay, I didn’t make any real mistakes, but the car was so much easier to drive. It was a good win, sure, but, compared with Estoril ‘85, it was nothing, really.

“The champagne for sure had a special taste that day.”

This article is adapted from a piece originally published on Formula1.com in 2015

Share

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

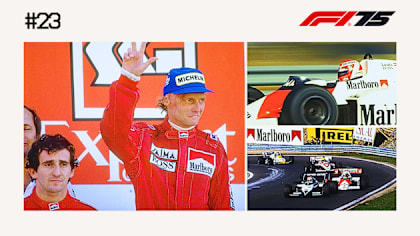

FeatureF1 Unlocked GREATEST RACES #23: An F1 title decided by just half a point – 1984 Portuguese Grand Prix

Feature NEED TO KNOW: The most important facts, stats and trivia ahead of the 2025 Spanish Grand Prix

News ‘It was great to witness’ – Alonso reflects on how Newey’s presence in Monaco impacted ‘level’ of Aston Martin team

Podcast BEYOND THE GRID: Meet Simone Resta, the F1 designer who swapped Ferrari for Mercedes