Feature

‘One of the most outspoken, colourful and intellectual men in motorsport’ – Max Mosley remembered

Share

Max Mosley, who has died at the age of 81, was one of the most outspoken, colourful and intellectual men in motorsport.

At times urbane and a highly amusing lunch or dinner companion, he knew how to fight when the gloves came off, and those who opposed him quickly found that they under-estimated him at their peril.

Born on April 13th, 1940, he ought to have been a politician, and indeed for a while he continued to harbour that ambition. But his father Sir Oswald had founded the British Union of Fascists, and the stigma of that parental history militated against pursuit of that dream.

He qualified instead as a barrister, but drifted into motor racing in the mid-Sixties. With characteristic boldness, after a season of Clubman’s racing he jumped straight into Formula 2, and vividly remembered competing at Hockenheim in the dank race in which the legendary Jim Clark was killed.

READ MORE: Former FIA President and F1 safety pioneer Max Mosley passes away, aged 81

Max Mosley with March co-founder Robin Herd in Austria

“It all came as something of a shock,” he once confessed. “I remember sitting on the grid for the first heat; I wasn't right at the back. And there was Graham Hill only a row before me, and Jim Clark not that much farther up. I was thinking ‘What the hell am I doing here? There are all these world stars and I'm really just a Clubmans driver. And it's raining. I’ve never driven in the wet before. I must be mad!’

“You can imagine if you were a club driver today, and you were there sitting on a grid with Senna and Schumacher...”

In 1969 he joined with university friend and designer Robin Herd, racer-cum-team manager Alan Rees, and businessman Graham Coaker, to form March, whose name was based on their initials.

Their first product was a Formula 3 car for Ronnie Peterson, but as only he could, Mosley formed a grand vision to compete in F1. And he committed the nascent organisation to create a Grand Prix car, too. He had created an unprecedented race against time.

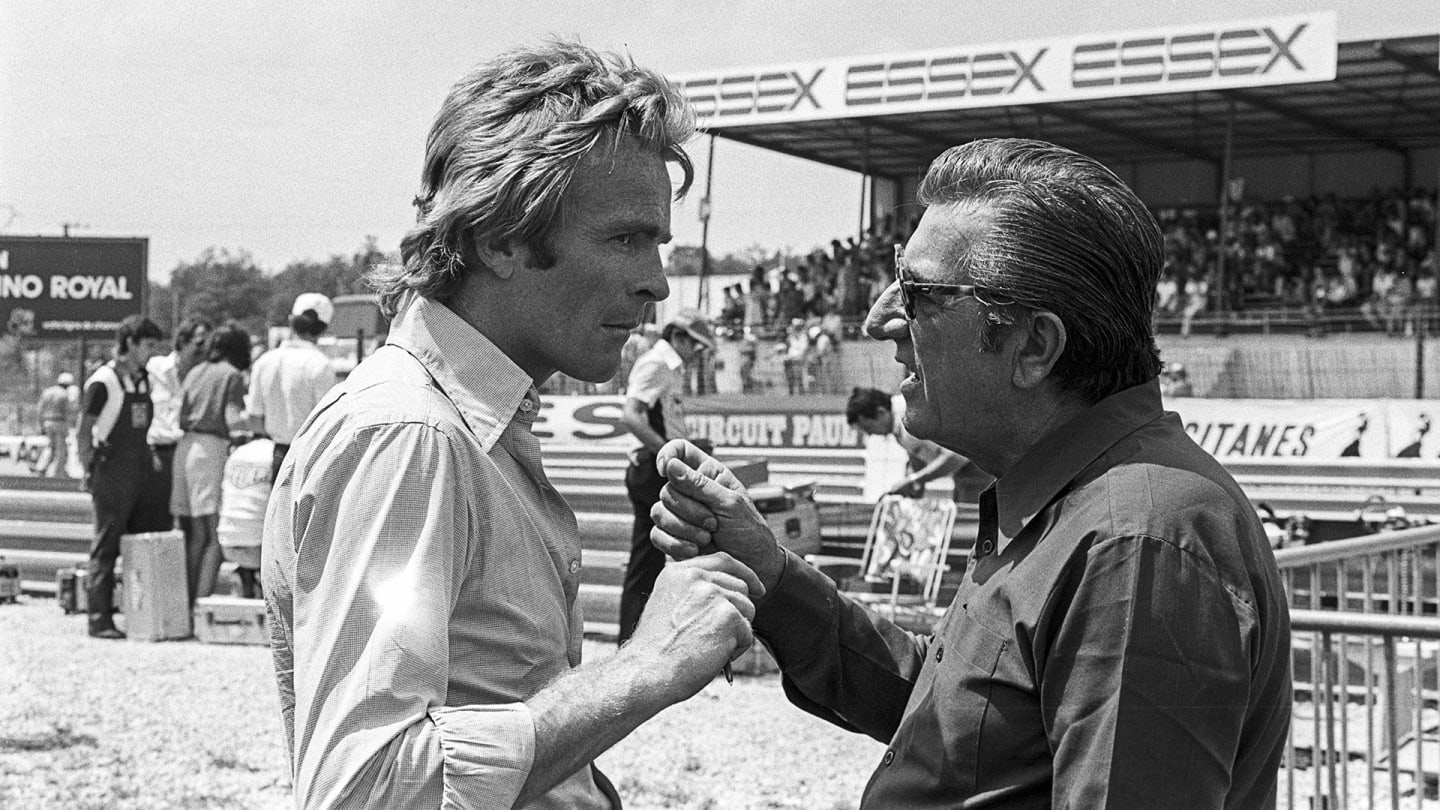

Max Mosley with Jean-Marie Balestre, who he succeeded as President of the FIA in 1991

Herd recalled, “I was told by Max 10 weeks before the launch event for March Engineering’s F1 effort: ‘We are going to run the car at Silverstone in front of the world’s press. One for the Ferrari number one driver and one for the World Champion. ‘No problem, Max! No problem! It’ll be all right.’ That was the birth of the March 701, so of necessity it was thrown together from a bunch of bits.”

They not only won that race against time, but in the opening Grand Prix of 1970, in South Africa, March 701s driven by reigning champion Jackie Stewart and highly rated New Zealander Chris Amon took the first two places on the grid.

Sensationally, Mosley had spotted the need for proprietary F1 cars and forced his colleagues at March to satisfy the demand. But even that leap into the limelight was not enough to satisfy him. Cynics might have deemed March a ‘Much Advertised Racing Car Hoax’, but it wasn’t. Besides F1, that year March manufactured Formula 2, 3 and Ford cars, and a CanAm sportscar. Later they built Indycars, too.

Much of it was hype, but Mosley needed that as he juggled the finance to keep the venture afloat. March went on to win three Grands Prix between 1970 and 1976, as well as countless F2, F3 and Indycar races. When its star finally faded, Mosley dipped into motorsport politics.

Mosely and Ecclestone formed a formidable duo during their time together in the sport

He and Bernie Ecclestone formed a fearsome alliance that proved all but unbreakable, and Mosley played a crucial role when Ecclestone won the fight for the commercial rights to F1 with unpredictable FIA president Jean-Marie Balestre. In time, that victory made many F1 team owners very wealthy men as F1 grew exponentially.

By 1991 Ecclestone and Mosley were ready to pounce, and Mosley sensationally deposed Balestre to take control of running the sport.

In 1994, in the wake of the fatal accidents of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna at Imola, Mosley was quick to realise that action was needed to head off increasing global criticism of motorsport, for these had been very public deaths on live television.

The changes he decreed were unpopular, but when the Benetton boss Flavio Briatore returned to the paddock after a teams’ meeting in Spain soon afterwards, to declare “Mosley is finished!” he could not have been wider of the mark. Mosley was a survivor, and he fought tenaciously and without mercy to ram the changes through.

Max Mosley with Lewis Hamilton and French Rally World Champion Sebastien Loeb at the 2008 prize giving gala in Monte Carlo

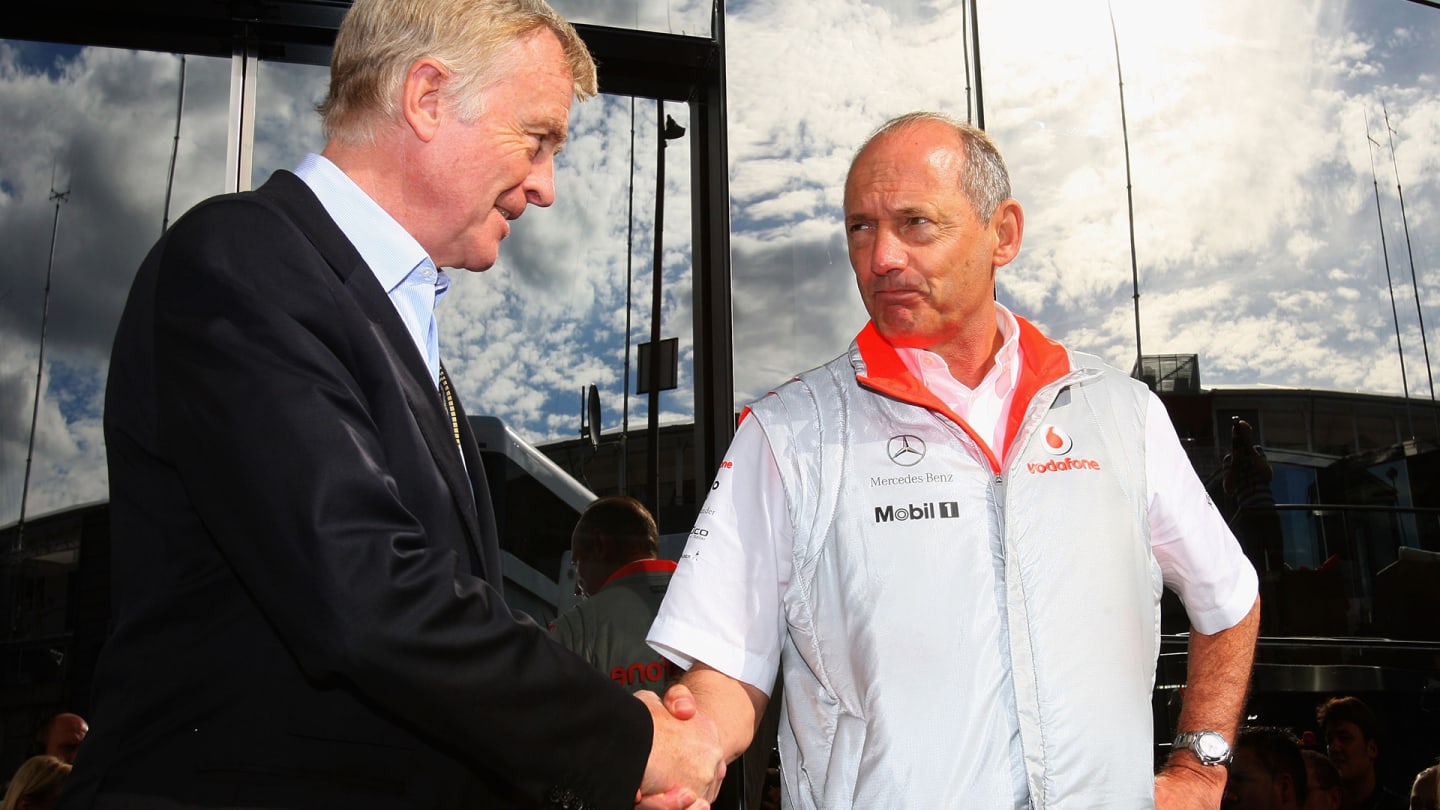

In 2007 his war against McLaren chief Ron Dennis was widely regarded as a personal vendetta, as he publicly accused the team chief of cheating amid the so-called ‘Spygate’ saga. Mosley delighted in embarrassing Dennis when he forced him into a public handshake at the Belgian GP.

“I think the world of Max,” Herd once said. “Like all of us, he has his faults. But he was the best colleague I had to work with in my life. He was sensational. Totally loyal, and we never had a falling out.

“But Max is black and white. I remember once in the early days of March, in 1973, we went to a restaurant in King’s Road, and James Hunt had just got his March. Another driver was there too, but all round the table there wasn’t space for one more. Max put that guy on another table and said: ‘You can see who isn’t the March driver, can’t you!’ That stuck in my mind… He can be so cruel, and he loathes Ron. But why? He just makes up his mind, and that’s it…”

Max Mosely and then McLaren Mercedes Team Principal Ron Dennis shake hands at Spa after the 'Spygate' saga

Behind the scenes, however, he made a significant difference. One of his greatest achievements was to see the introduction of mandatory crash tests for F1 cars, which undoubtedly saved lives, and that remains part of his legacy, as does the similar EuroNCAP rating system for road cars, after he brought F1 engineering methodology to bear.

Hundreds of thousands of drivers across the globe benefited from the latter.

Many predicted his downfall in March 2008 when he was embroiled in a scandal over his personal life which was revealed in a sting by the News of the World newspaper. But Mosley brazened it out. He was completely unperturbed and made it clear that he had absolutely no intention of standing down from his role as FIA president, insisting that what he did in his private life was just that.

He faced down his critics, and retired from the FIA when he was ready, as Jean Todt succeeded him in 2009.

Max Mosley retired from the FIA in 2009

"I don't mind flak.” Mosley, who had fought a pitch battle on the streets of East London in 1962 during one of his father’s controversial rallies, once said. “I come from a family where we have had flak all our lives, but I realise some people do. I love reading the blogs when they are being furious about me, it's very entertaining."

His bravura performance eventually saw the demise of that Sunday newspaper, and in more recent years he devoted himself to passionate advocacy for new rules against media intrusion.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Feature EXCLUSIVE: ‘I’m here for the grind’ – Nico Hulkenberg on his Sauber return, Audi’s impending arrival and targeting F1’s top step

News ‘We have a duty of care to protect and develop Liam’ – Horner opens up on decision to replace Lawson at Red Bull

Video LIVESTREAM: Watch the action from Qualifying for Round 10 of the 2025 F1 Sim Racing World Championship

News Alonso thankful to avoid ‘massive crash’ after ‘super scary’ brake failure that ended his race in China