Feature

Remembering Ronnie Peterson - F1 Super Swede

Share

There were many reasons fans adored Ronnie Peterson, but two of the most significant were the way he drove and his personality. Forty years after his death at Monza, David Tremayne tells the story of Super Swede.

The photographs belong to the same classic genre as that wonderful Michael Tee shot of Juan Manuel Fangio in a four-wheel drift at Rouen.

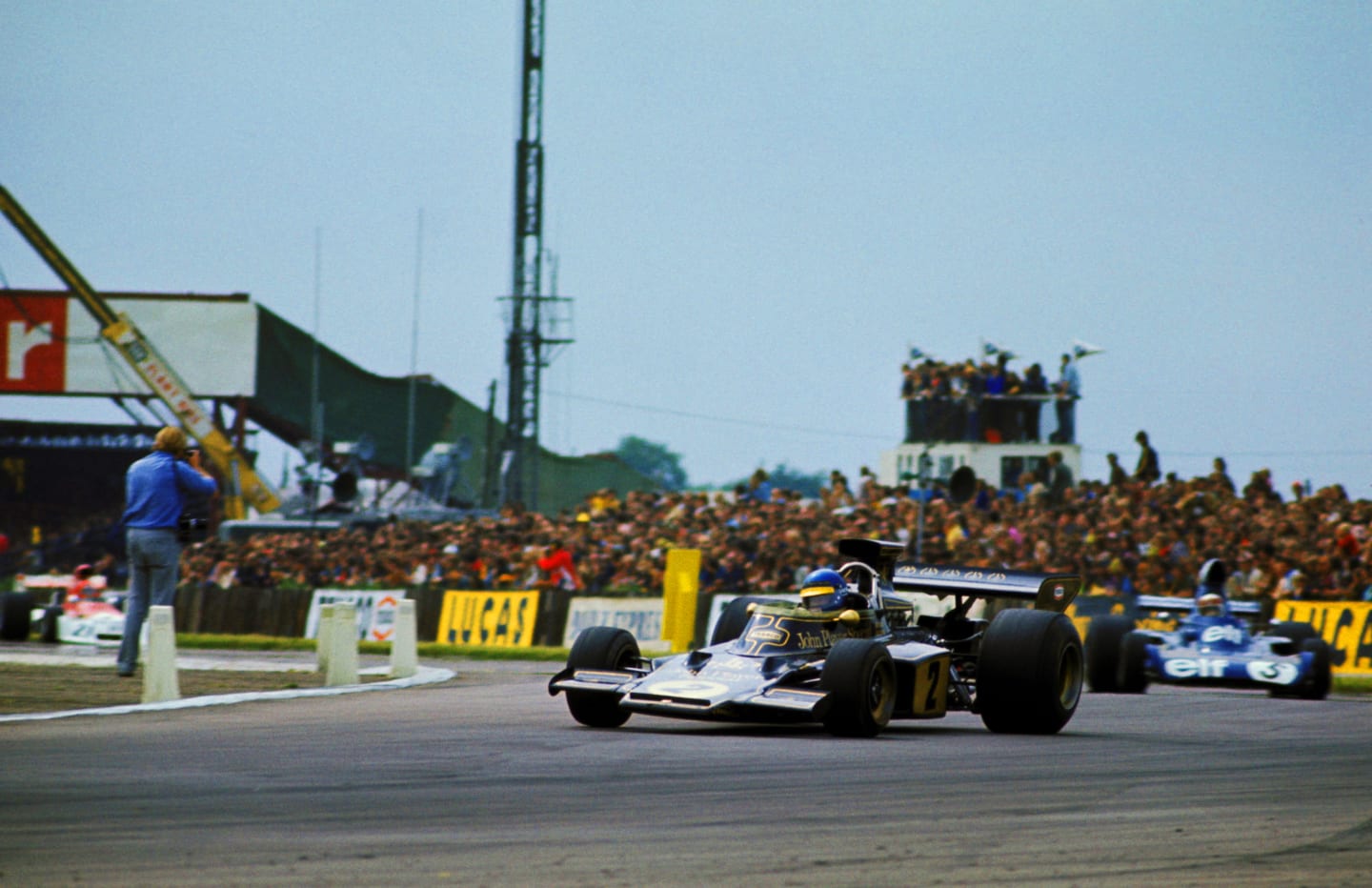

A black and gold Lotus 72 dances on the edge of adhesion at 150 mph through Silverstone’s chicane-less ‘old’ Woodcote corner, back in the days when the high-wire artistes of the era were still able to demonstrate their other-worldly talent without a safety net. Ronnie did not just make the Lotus slide – he made it dance, its continued forward progress dependent upon its driver’s extraordinary talent and will rather than the laws of physics.

Peterson leads Jackie Stewart through Woodcote in 1973

The handsome blonde Swede made his F1 debut in Colin Crabbe’s yellow and brown Antique Automobiles March 701 in 1970, the season in which Jochen Rindt posthumously won the World Championship in the innovative Lotus 72. And in so many ways, Ronnie was the Austrian’s natural successor. He took over not just his mantle as the king of Formula 2, but as the most spectacular man in the big league. And, like Jochen, it would be many years before he finally had machinery that did him justice.

Monza had traditionally been benign to Ronnie. In 1971, he just missed his first Grand Prix win by 0.1s. In that five-car blanket finish of those pre-chicane days, his March 711 crossed the line neck-and-neck with Peter Gethin’s BRM P160. The two were visually inseparable. “Just to make sure, I threw my hand up,” Gethin, a jockey’s son, said. “I figured that if it did ever come to a photo finish they would go for the guy who did that…”

Two years later, Ronnie won there for Lotus, as team mate Emerson Fittipaldi vainly waited for team boss Colin Chapman to signal the Swede to move over and let him pick up the breaking threads of his own diminishing World Championship chances. Ronnie repeated the victory in the same car in 1974, and in a March 761 in 1976. But in 1978, his entire weekend was a nightmare.

His relationship with Chapman, never great, had soured by 1975. He’d had enough of struggling with the ageing 72, the new-for-1974 Lotus 76 had been a flop, and at the beginning of 1976, the all-new 77 seemed no better. The previous year, there had been talk of swapping him with Tom Pryce at Shadow. Now he went back to his spiritual home, March, before a disastrous year with the six-wheeled Tyrrell in 1977.

The Swede's preferred way of getting through Monza's Parabolica...

When he returned to Lotus, there was even less warmth with Chapman, and his contract stipulated that he had to play second fiddle to Mario Andretti, who had played a crucial role in the development of the Lotus 78 and the 79.

It said everything about Ronnie’s character that he not only acquiesced, but honoured the deal. More than that, he never embarrassed Mario on the occasions when he was demonstrably quicker.

“Look at the history books,” he would tell friends. “Never ever has there been a driver winning all the Grands Prix. I will have a chance to win races and the title.”

He won in South Africa and again in the rain in Austria, where he drove with all of his legendary elan as Mario crashed on the opening lap, and though he was frequently the pole winner, he duly backed the American in one-two finishes in Belgium, Spain, France and Holland. In the latter, many felt he could have overtaken Mario at any time, but he held station again and said he’d had fading brakes.

Relations were frosty between Peterson and Lotus boss Colin Chapman

Andretti hadn’t initially wanted him in the team. “Tell me where it’s written we need two stars,” he'd said. He had always liked Ronnie – there was nothing to dislike – but seriously doubted that the arrangement proposed by Chapman could work.

“When I signed my Lotus contract for 1978, it was as number one. I mean, that was unequivocal,” he explained. “I felt it was my due. And Ronnie signed as number two…”

At Monza, the engine in Ronnie’s Lotus 79 broke early in Friday practice, obliging him to switch into the 78, which he professed not to like and which had a significant straightline speed disadvantage compared to the later car. On Saturday, overheating brakes and a baulky gearbox further hampered the 79. And, for much of the time, he was accompanied by a small lizard that had somehow found its way into the cockpit!

Andretti quickly became a close friend

In the circumstances, qualifying fifth was impressive. But then the rear brakes, the 79’s Achilles’ Heel, failed in the race morning warm-up and his race car was badly damaged. He would have to use the 78. Besides that straightline speed problem, it also lacked the 79’s strength in the footbox area…

Team personnel would later report that Chapman would, in darker moments, unfairly blame his overworked mechanics for not putting sufficient effort into preparing another 79, which would have been the spare car in Italy.

Mario’s initial wariness had given way to an enduring admiration and friendship. Going into the Italian Grand Prix, he and Ronnie were separated by only 12 points, with three races left. The battle was not over.

Peterson practises around Monza on that fateful weekend

Journalist Freddy af Petersens was the witness to a remarkable scene between them in the Lotus motorhome after qualifying.

“Mario came to regard Ronnie as a true friend and said to him, ‘Let’s drive this race according to the contract, but the last two races you and I will race for the title and the hell with the contract. Because I don’t want to win it with the whole world believing that you were not allowed to pass me.’ It’s why Mario was even more devastated when I was the one who broke the news about Ronnie to him...”

The late and much-missed writer Alan Henry was also a close friend of Ronnie’s. “I can take you absolutely to the point in the Monza paddock where I bumped into Ronnie on race morning, and he said: ‘Morning Albatross’. We’d educated him and Niki to the existence of Monty Python, and that’s what he called me. He was wearing dark glasses and those very distinctive yellow overalls, and we shot the breeze. It was after the morning warm-up, after he’d crashed the 79. Then he said, ‘See you later’ and that was it. I remember it like it was yesterday.”

The aftermath of the crash. Peterson can be seen lying in the middle of the track in his yellow overalls

Henry witnessed the 10-car accident in the first chicane. James Hunt would later blame Riccardo Patrese and conduct a witchhunt against him, but Arrows boss Jackie Oliver said: “Dutch TV film shot from the front and side shows Riccardo go across in front of James with feet to spare. He did not touch James at all.”

It was the Englishman’s McLaren that made contact with Peterson’s Lotus and pushed it into the barrier at 100 mph. As the impact tore off the front end of the 78, Ronnie sustained severe leg injuries. As a marshal played an extinguisher on the blazing wreckage, an anguished Hunt and Clay Regazzoni dragged Ronnie clear. Together with an injured Vittorio Brambilla, who’d sustained a head wound crashing his Surtees, he was taken to the Niguarda Hospital in Monza.

“I was sitting in the press grandstand on the outside of the main straight, and there was this blinding flash of flame, the impact as he hit the barrier,” Henry said. “I remember reports saying he’d be fine. But I heard myself say, ‘I don’t think we’ll see Ronnie again.’ I still have no idea why I said that.”

The prognosis seemed good. Ronnie’s legs were badly broken and there was talk of a toe having to be amputated, but he would recover in time to take up the contract he had signed in Holland to drive for McLaren in 1979.

"Mario was devastated when I broke the news about Ronnie to him" - Freddy af Petersens

“I went back to England that night on the plane, got to Motoring News’ printers at Chelmsford and had a conversation with Hilary Weatherley, the ad manager,” Henry recalled. “He told me at nine o’clock on Monday morning: ‘Ronnie’s dead.’ He got quite angry when I accused him of joking, but I just couldn’t take it in. I had no idea what had taken place in the intervening hours.”

The accident had taken the edge off Andretti’s triumph in the World Championship, as sixth place (after he had been penalised a minute for jumping the start) gave him a score that could not now be beaten. Emerson Fittipaldi called him the following morning. The news about Ronnie was not good. There were complications. Mario and his wife Dee Ann drove fast to the Niguardo, and arrived in time to meet the Fittipaldis and Freddy Petersens, who told them that their mutual friend had succumbed to a pulmonary embolism.

“I drove down the road a little way and then stopped,” Andretti said. “What was there to say?” Journalists besieged him, but for once he had little for them. “Unhappily,” he said, “racing is also this.”

“You know, I wouldn’t say Ronnie was Einstein, but he was a typical Swede,” Petersens remembered, “which meant that he was shy. He would talk to you, but to get the good answers, he had to trust you. He had quite a few fights with the Swedish press because of that. If he said there were some technical things wrong with the car, they would write that he wasn’t a good driver. They did not understand motorsport, and its ups and downs. That’s why he was very selective. But once he trusted you, he would give you his shirt if you needed it. To me, he was a goldmine.

“There were few young racing drivers popping up in Sweden, so when they did, Ronnie started to help them through the jungle. Eje Elgh [now associated with Marcus Ericsson at Sauber], would have been racing in F1 thanks to Ronnie, had he not injured his arm in a testing accident. I wouldn’t say Ronnie was a father figure, but he was a role model, someone they looked up to. He would gladly help young drivers. He started as an elevator repair man, but racing was his life, from the day he sat in that homebuilt car until Monza. He couldn’t have done anything else. Lousy test driver, a really bad test driver. But an absolutely wonderful racer.”

Peterson relaxing with his wife Barbro

Henry also remembered his friend with great fondness. “When I first started, I didn’t understand the subtleties between one driver and the other. The first impression came when I was standing on the inside bank at Gerard’s at Mallory Park in practice for the Formula 2 race in 1971. When Ronnie was on a quick lap in that yellow SMOG March you could see the whole suspension flexing as it sat down on its left front with a slight bit of oversteer. He was just in a different class. I remember thinking: ‘For crying out loud, so that’s how you drive these things.’

“He was like a slightly bewildered Hakkinen. Mika was very philosophical towards misfortune. Ronnie was too. He had enough, Heaven knows. It was always as if he was floating slightly on a mental cloud, just drifting through life. He was a gentle bloke, but he had a very shrewd underlying feeling; he knew where he sat in the order of things. He wasn’t a softie. He knew he was right at the very top. He was very shy, but he always had quite good people negotiating for him – Count Googie Zanon, and his manager Stefan Svenby, who was quite astute. There was a steel core just below the surface of his rather cuddly personality.”

Henry paused, and ultimately failed to finish his final sentence. “It was,” he began very quietly, “the first time in a long time I can recall having that prickly feeling in my eyes…”

"It was the first time in a long time I can recall having that prickly feeling in my eyes" - Alan Henry

When his career was in the doldrums between 1973 and 1978, Ronnie never lost hope that the good days would come back, that he would win again. Life was a race to him. And that was why so many people loved him. That, and his spectacular car control that made every corner a visual adventure he shared with the fans.

Ronnie Peterson was that rarest of all racers: a superstar without an enemy in the paddock.

WATCH: Ronnie Peterson in tribute

Ronnie Peterson: The Super Swede

Share

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Report Piastri storms to controlled victory in Bahrain Grand Prix ahead of Russell and Norris

Report Piastri beats Russell and Leclerc to pole position during Bahrain Grand Prix Qualifying

Feature FACTS AND STATS: Piastri the first repeat polesitter of 2025 as he takes second Grand Prix pole in Bahrain

FeatureF1 Unlocked STRATEGY GUIDE: What are the tactical options for the Bahrain Grand Prix?