Technical

TECH TUESDAY: How Ferrari and Hamilton pushed Mercedes to create the masterful W11

Share

The basic concept of last year’s Mercedes may have been good enough to win the title in 2020 with a few key updates, but the Silver Arrows took it one step further with the W11. Mark Hughes, with technical illustrations from Giorgio Piola, explains why the W11 has been such a dominant machine, and how its success was catalysed by 2019 contenders Ferrari and seven-time champion Lewis Hamilton.

Mercedes returned to 2014 levels of domination this year. Their average qualifying advantage over the best of the rest was almost 0.7s, a huge improvement on last year (when it was 0.13s). Partly this was down to the difficulties experienced this year by Ferrari and Red Bull, but it was also very much a reflection of the masterpiece W11 design.

READ MORE: Why the 2021 aero tweaks combined with new tyres could shake up the order next year

Despite being conceived as a car for what was going to be the final year of this formula (a formula which has since been extended by a year), it was a radical reworking of the existing concept. Even a mild update of last year’s car would likely have been good enough to win this year’s title, but the team is not wired liked that and continued to push the boundaries. This applied to both the power unit and the chassis.

The basic architecture of the power unit remained as before but very significant gains had been made in the combustion process, which, in this hybrid formula, accumulate. The Mercedes unit was the only one which significantly increased in power despite the stricter technical directives of 2020. The impetus for this intense development came, ironically, from Ferrari’s power advantage of last year. Ferrari’s significant loss of power into this season only amplified the effect of the Mercedes gains.

READ MORE: F1's 'Party mode' ban – What are the changes to engine modes and why do they matter?

Mercedes' 2019 and 2020 cars compared

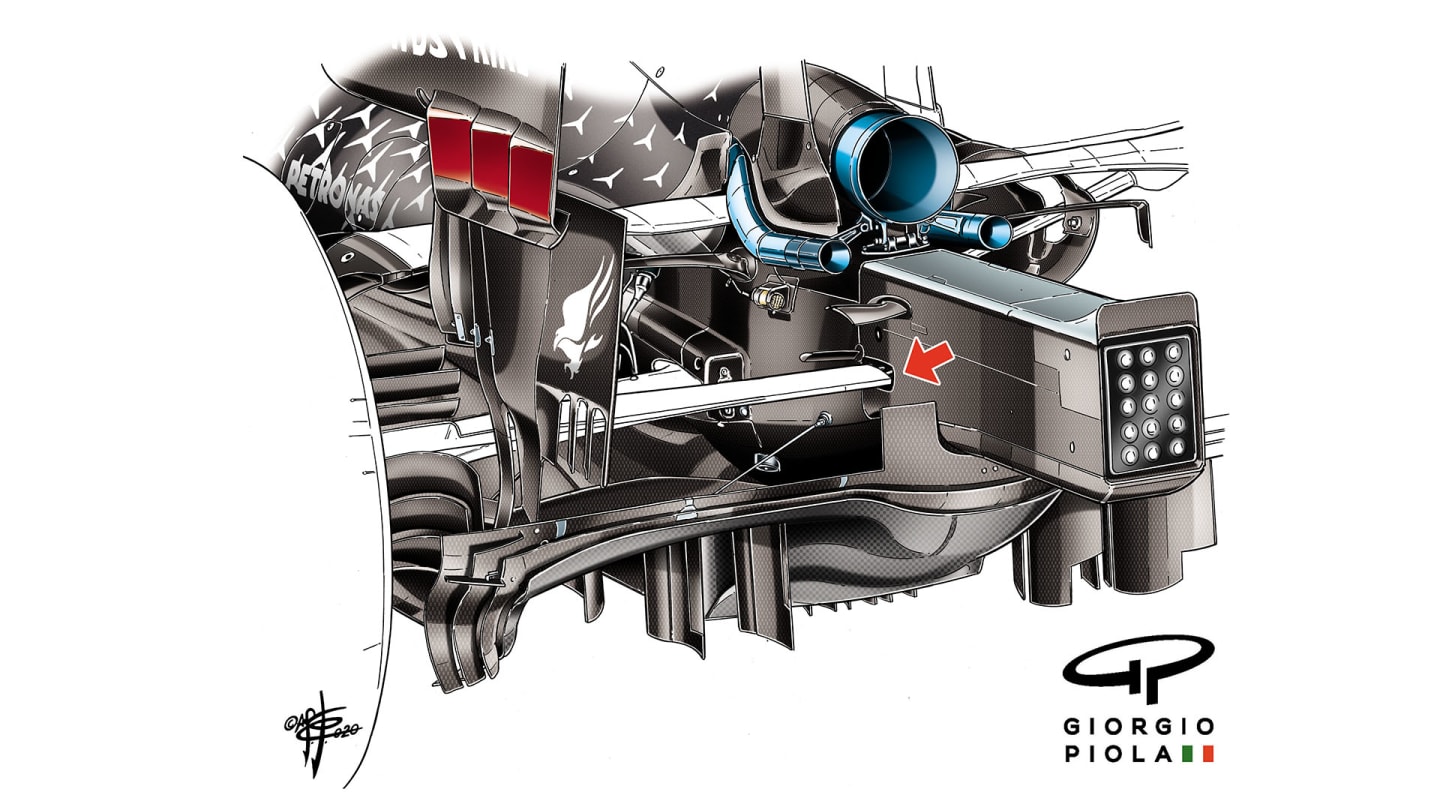

Far more visible than the magic inside the combustion chambers, however, was the chassis. It retained the same long wheelbase as every Mercedes since 2017 – but pretty much everything within it was different. By far the most significant new feature was its rear suspension, which through being swept back to an extreme degree, created a big area of extra volume between the tyre and diffuser to enhance downforce creation.

The way this was achieved was by mounting the inboard part of the lower wishbone not into the conventional place of the gearbox but into the crash structure behind.

This was extremely ambitious from a structural point of view in that the crash structure still has to pass the same stringent rear impact test (deforming by a defined amount and with defined peak loads after being impacted by a 780kg weight at around 25mph). In the test, the structure had to absorb the load before reaching the suspension mounting point, which would otherwise have sent the loadings beyond the permitted peak.

READ MORE: How much have Red Bull, Racing Point and Ferrari closed the gap to Mercedes in 2020?

This was all part of changing the dynamics of the car in the way that Lewis Hamilton had been pushing for.

The rear suspension on the Mercedes W11, with a red arrow showing how the rear leg of the lower wishbone feeds into the crash structure – underlining how tight the rear suspension layout on the W11 is

He related earlier in the season that last year’s car did not rotate quickly enough for him into slow corners – i.e. the initial transition from straight ahead to pointing at the apex was not sharp enough. “Because we’ve have had long cars we’ve had great downforce but been quite poor in low-speed corners,” he explained.

“The car would not rotate as well as we’d like. There’s a limitation with these tyres. The front has a limitation, the rear has a limitation, grip wise. There’s saturation, there’s thermal deg and there’s only a certain amount you can do with the mechanical balance before it affects the other end. It’s like a see-saw. The front was a lot more understeery last year; you struggled a lot more when you went over the tyre and no matter how much you changed the mechanical balance it didn’t really fix it.”

READ MORE: A look at the W11 upgrades that show how hard Mercedes are pushing to stay ahead

What Hamilton was chasing was the sharp direction change of a shorter car. But getting a longer car to change direction more quickly imposes greater loads on the rear tyres than would be the case with a shorter one.

The rear needed more grip to be able to withstand the sudden increase in load from a more aggressive direction change. That’s what the new rear suspension layout facilitated through greater downforce. In this way, with the W11 Hamilton was getting to have his cake and eat it.

The floor has been tweaked ahead of the rear tyre, with an array of three vanes to deflect air around the tyre on what is an aerodynamically sensitive area

The engine was moved slightly further forward in the chassis to rebalance its weight distribution – and this necessitated a slightly longer input shaft into the gearbox. It was the greater vibrations from this longer shaft which created the problems with the gearbox sensor at the first race in Austria. The front suspension was changed where it fed into the wheel rims which involved re-engineering the uprights. This was also for aerodynamic gain.

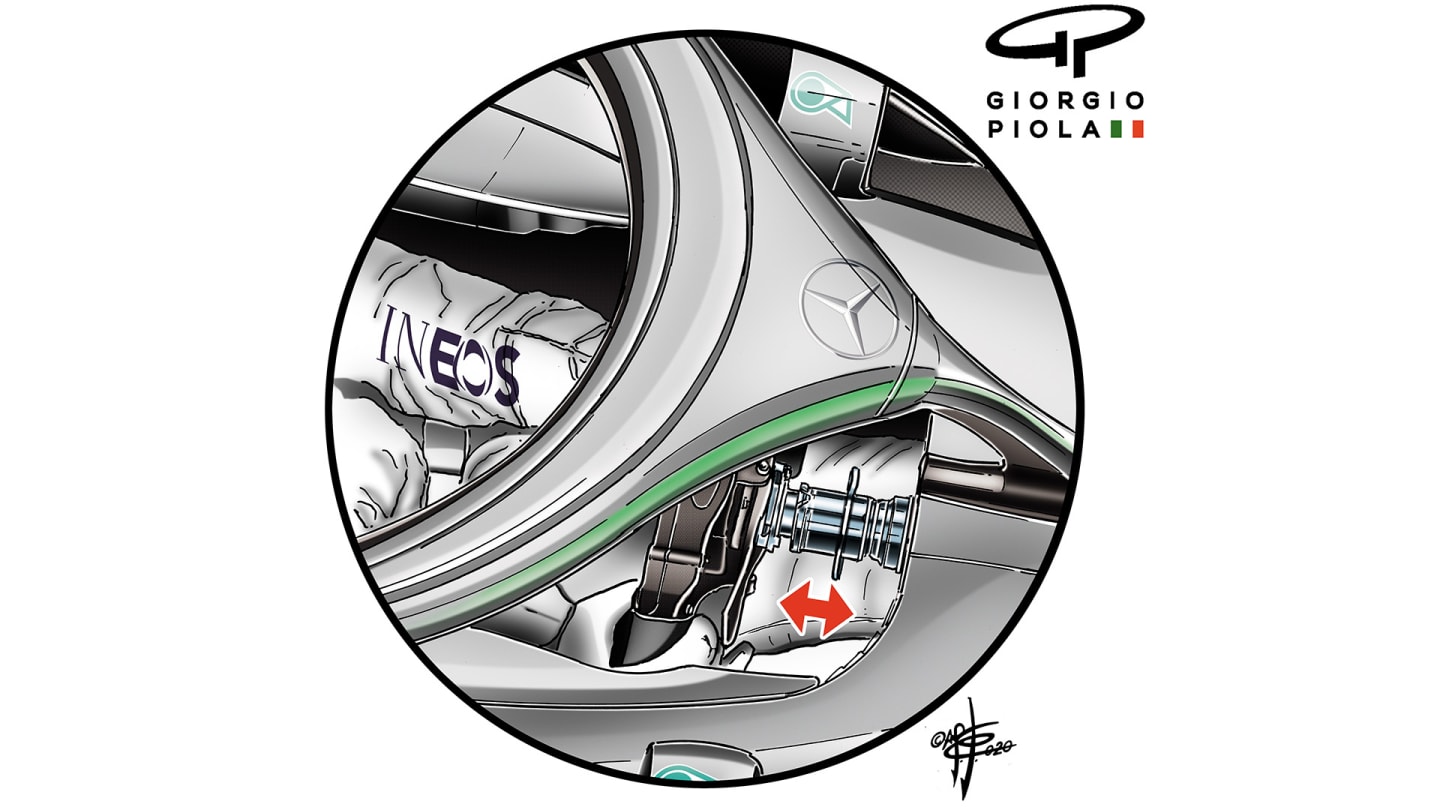

READ MORE: Why DAS is only the second most impressive innovation on the Mercedes W11

Then there was the infamous DAS (dual axis steering) system whereby the steering column could be moved between two positions which altered the toe angle of the front wheels, thereby helping the drivers get more heat into the tyres prior to a qualifying lap or on a safety car restart. This feature has been banned from 2021 so as to close down an area of expensive development.

It is a landmark design car in its cleverness and cohesiveness and this has been reflected by its overwhelming margin of superiority.

A technical drawing of the cockpit tweak that is used to control Mercedes' ingenious DAS system

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News 'Reasonable' – Horner gives his verdict on Tsunoda's points-scoring Bahrain GP as he explains cause of Red Bull pit stop issues

News United States Grand Prix headliners confirmed as 36 hours of entertainment returns to COTA

News McLaren bosses hail ‘perfect weekend’ from Bahrain winner Piastri – but warn that it’s ‘a matter of time’ before ‘epic battle’ with Norris

TechnicalF1 Unlocked TECH WEEKLY: Was Ferrari’s Bahrain floor upgrade a success – and will it help them at the twisting Jeddah Corniche Circuit?