11 - 13 April

Technical

TECH TUESDAY: Red Bull and Ferrari's wildly different solutions to the challenge of Jeddah

Share

Red Bull and Ferrari traded laps at the top in Saudi Arabia, but the two teams took different journeys towards their towering pace. Mark Hughes examines their respective approaches to set-up while Giorgio Piola provides technical illustrations.

Last weekend in Jeddah there was a lot of experimentation with wing levels from almost all of the teams. The Saudi Arabian circuit features an extremely high proportion of the lap running at full throttle, and is second only to Monza in its lap time sensitivity to aerodynamic drag.

F1 NATION: Verstappen, Newey, Horner, Steiner and Norris review the Saudi Arabian GP

But each design of car will vary in where exactly the perfect trade-off between downforce and drag is. Furthermore, because this was just the second race for the new aerodynamic regulations, teams were still finding out about how their cars responded to various settings in the real world as opposed to simulation.

There is the further complication of the porpoising phenomenon. The bouncing suffered by some cars as the underfloor airflow stalls when the floor gets too close to the ground means that what was the ideal level of wing in simulation is no longer so in reality. Mercedes, for example, are one team which are surrendering a lot of the downforce that simulation suggested was available, just in order to keep the porpoising under control.

Show and tell: Mercedes updates in Saudi Arabia

Those teams struggling with porpoising would tend therefore to run with the lowest of the rear wings. Those teams less afflicted may have found it advantageous to run slightly more downforce because although straight line speed is very important here, a similar lap time can often still be achieved with a medium downforce level of wing. Because such a wing would give more grip under braking and through the seven turns on the ciruit that are not flat-out, the straight line speed disadvantage is sometimes not that great.

It is not the speed attained at the end of the straight which is important; rather it is how long it takes to get from the beginning of the straight to the end – and if you are entering it faster because you’re quicker through the corner leading onto it, it can be that you lose very little time on the straight despite going much slower at the end of it. Plus, greater downforce tends to protect the tyres better, allowing faster race stints.

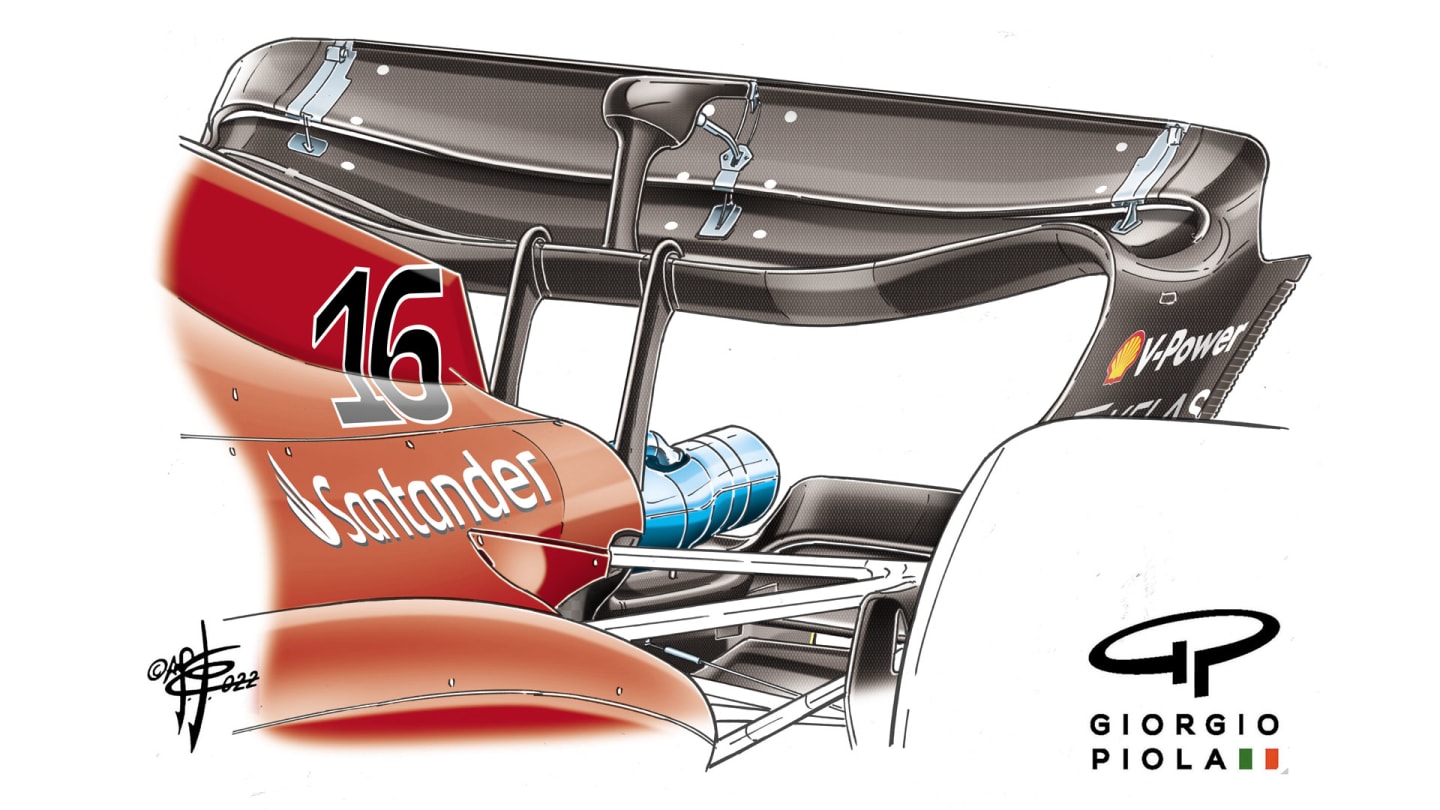

This is the direction which Ferrari followed. As can be seen below, there was very little difference between their Bahrain and Jeddah wings, despite the Bahrain track being considered a medium-high downforce circuit.

Ferrari's Saudi Arabia wing set-up (top) and their similar Bahrain wing (bottom)

Ferrari favour a spoon-shaped mainplane (the lower of the two parts of the assembly) with a quite deeply-dished central section and very slim at the outboard ends. It is the mainplane rather than the flap (the upper part of the assembly) behind, which creates most of the drag.

We can see that Ferrari’s Jeddah wing, while much the same in general profile as that used in Bahrain, is less deeply dished in the middle. It’s a low-downforce wing but not that low-downforce.

An in-depth illustration of Ferrari's Saudi Arabia-spec rear wing, with a shallower-dished mainplane

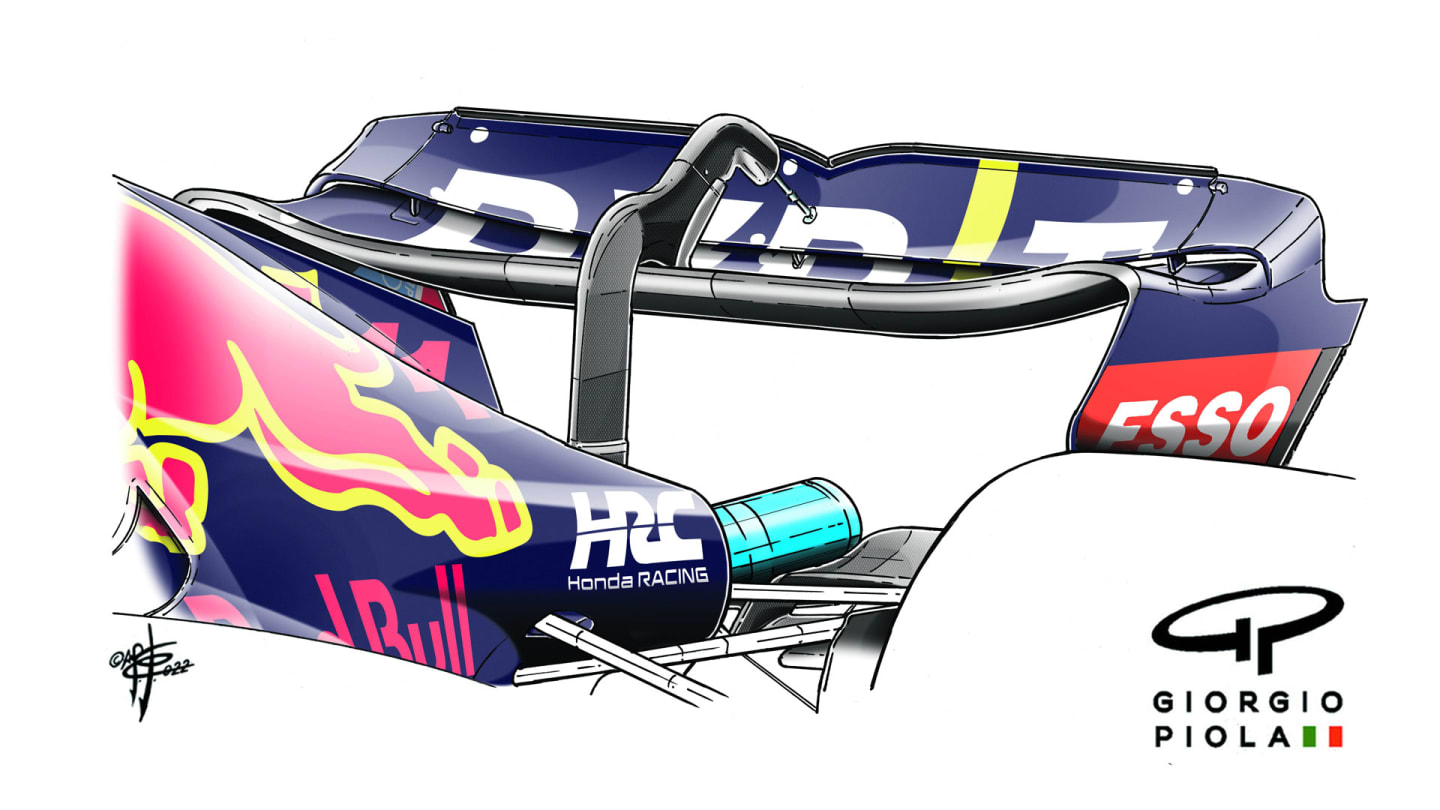

Red Bull tried their Bahrain wing during Friday practice in Jeddah but eventually settled on a lower downforce setting – and their low-downforce wing is evidently lower in downforce than that of the Ferrari. Although their Bahrain mainplane is spoon-shaped, their low-downforce wing used in qualifying and the race in Saudi Arabia has a very straight-edged mainplane with only a tiny tapering away at the outboard ends.

The big central area of the Bahrain wings will create a lot of drag and downforce and the outboard ends are trimmed away because that part of the wing creates less downforce than the central section anyway (because of the interference of the endplates). So because it is contributing less downforce there, it is advantageous to cut it away there in order to reduce the drag.

READ MORE: How Verstappen solved the tyre puzzle to win in Saudi Arabia

But the straight-edged mainplane used in Jeddah has a small section right across its width and so there is hardly any mainplane area available to cut away. Such a small mainplane area will induce very little drag – and relatively little downforce.

So we saw in Jeddah that the Ferrari was quicker through the corners and under braking; the Red Bull faster at the end of the straights.

Red Bull's Saudi Arabia wing (above) was markedly different to their Bahrain wing (below)

But we also saw a similar pattern in Bahrain between the two cars, when they were running higher downforce. Although there were certain corners in Bahrain where the Red Bull was faster than the Ferrari, generally the Red Bull was faster at the end of the straights, but the Ferrari’s better acceleration was combatting the lap time effects of that.

So it seems that in both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, two circuits with quite different downforce demands, Ferrari preferred more rear wing than Red Bull. There could be many reasons for this. If the Red Bull has an underfloor which is generating more downforce than the Ferrari’s, it won’t need as much rear wing for the same total downforce.

MUST-SEE: Verstappen and Leclerc’s frantic duel for victory in Jeddah

But it may not be that simple. The rear wing and beam wing combination have an effect on the performance of the underfloor. The more the air is being worked over the underside of the rear wing, the greater pull it has on the beam wing below, which, in turn, pulls harder on the airflow coming through the underfloor.

So the bigger the rear wing, the harder the underfloor will tend to be worked. That sounds great in principle, as it implies you can just keep adding rear wing and the car will be faster! But of course there will come a point of diminishing returns where the drag penalty overcomes the downforce reward. But as a generality, a ground effect concept of car does encourage more rear wing than the previous generation.

The bigger the rear wing, the more the underfloor is working – but the drag penalty can start to outweigh the benefits

Now, if we put into this mix the porpoising phenomenon, it tends to impose an artificial limit on the downforce the floor is capable of generating. Because teams were generally unprepared for the porpoising when they were designing the cars, they probably have floors which, in their design, create more downforce than can be used.

One way of keeping them from inducing the porpoising is simply to increase the rear ride height, but that’s a very inefficient way of doing it. A better way of keeping the car away from the porpoising threshold can be to run less rear wing. In that way you at least gain the benefit of lower drag. Increasing the ride height simply dumps downforce for very little benefit in drag reduction.

The smaller rear wing used by Red Bull in Jeddah

So it may be that the Red Bull’s natural balancing point of rear wing downforce and drag is more efficient than the Ferrari’s and, hence, they can simply get away with less rear wing for similar downforce and that they doesn’t have a porpoising issue. OR, that actually they have to run less rear wing, because too much will tend to pull the floor into porpoising territory earlier than the Ferrari’s.

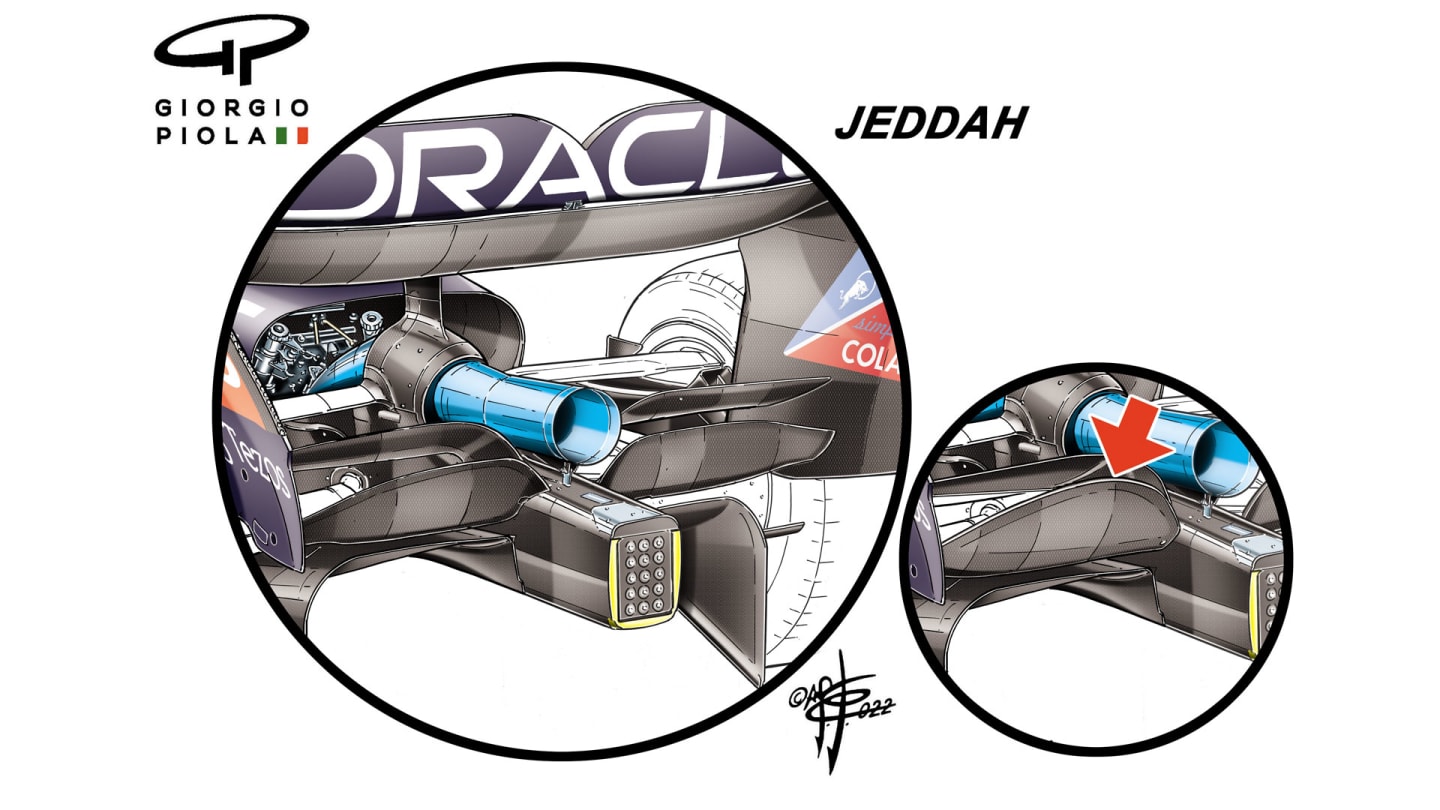

It was notable that Red Bull ran a less-aggressive beam wing in Saudi than in Bahrain. These too generate drag and the smaller flaps (above) used in Jeddah are part of the smaller rear wing package. But as well as generating less drag, this beam wing will also be exerting less pull on the underfloor airflow.

TECH TUESDAY: The power unit gains behind Ferrari's Bahrain Grand Prix 1-2

A smaller beam wing flap used in Jeddah (left) than in Bahrain (inset, right)

Whatever the reasons, it would appear that the Ferrari’s ‘happy place’ is with a higher rear wing level than the Red Bull’s. Another contributing factor to this could be the strength of the Ferrari’s power unit. GPS analysis suggests that it is extremely strong under acceleration. This might be what is allowing them to run more rear wing, for if it could be enabling the car get down the straight in the same amount of time despite being slower at the end of it.

As we get more data from a greater array of circuits, a clearer picture will doubtless emerge. But for now, F1’s two fastest cars are delivering their lap times in quite different ways.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News 'He's very exceptional' – Ex-Ferrari test driver Marc Gene lauds new recruit Hamilton but warns ‘there's a lot of pressure’ at the Scuderia

Live Blog AS IT HAPPENED: Follow all the build-up ahead of the Bahrain Grand Prix weekend

Feature BAHRAIN GRAND PRIX – Read the all-new digital race programme here

News The six rookie drivers set to take part in FP1 at the Bahrain Grand Prix