Technical

TECH TUESDAY: Under the bodywork of 1986’s best F1 car, the Williams FW11

Share

This Wednesday we’re introducing an extra mid-week race stream for your delectation – and we’re starting off with an absolute belter: the drama-filled 1986 title decider in Australia. The race was a three-way title fight between McLaren’s Alain Prost (the outsider) and the staunch favourites – Williams team mates Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell. The latter duo were driving what was undoubtedly that year’s stand-out car, and in a special retro-themed Tech Tuesday column, Mark Hughes gets under the bodywork.

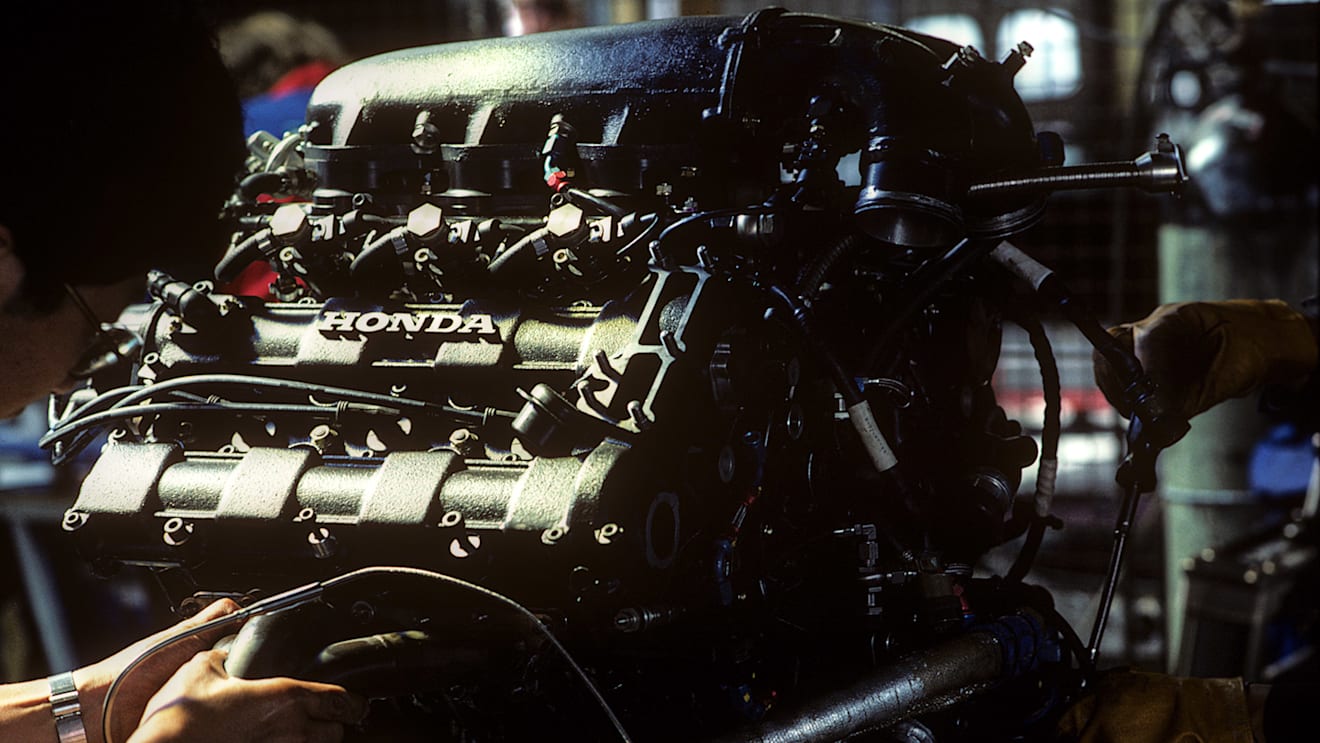

The state of the art F1 car of 1986 was without a shadow of a doubt the Williams-Honda FW11. A hugely powerful Honda engine allowed the Williams the luxury of being able to run more wing than its rivals. This, combined with a well-engineered (but quite conventional), carbon-fibre chassis with a good aerodynamic balance made for a formidable tool that Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet exploited to dramatic effect.

READ MORE: We’re streaming the 1986 Australian Grand Prix – here’s why you should watch

Although they both infamously lost out on the drivers’ championship (largely through taking points from each other) to McLaren’s Alain Prost, the car gave Williams their second world constructors’ championship, this being the first such title that Honda had been part of.

The FW11 was nowhere near as aerodynamically effective as a modern F1 car, but it was hugely powerful.

This represented the third year of the partnership between the British team and Japanese manufacturer, which had taken time to flower as both sides learned all about the intricacies and technical nuances of the incredibly highly-stressed 1.5-litre turbocharged engines of the time.

The governing body had already decided that the turbos were becoming too fast and had announced a glide path down to their planned ban from 1989. Since '84 there had been a maximum fuel limit of 220 litres – and for '86 this was reduced to 195 litres, ahead of boost limits in the following two seasons.

WATCH: Piquet’s amazing overtake on Senna in Hungary, 1986

Yet so fast was the technology advancing that Honda’s 1986 engine – the RA166-E – was more powerful than its predecessor despite the 11% reduction in the fuel limit. In qualifying trim, Mansell and Piquet were enjoying in excess of 1,100bhp (around 300bhp less than the Renault in Ayrton Senna’s Lotus), with significantly more than 900bhp (about 80bhp more than the less fuel-efficient Renault) in the races.

1 / 2

Formula 1 cars of today have similar power to the Williams-Honda but are 40% heavier (740kg compared to 1986’s 540kg) – so the machines of 1986 had a vastly greater power-to-weight ratio. On the other hand, they were nowhere near as aerodynamically effective and would be an estimated 10s per lap slower around Suzuka than a current car.

In this part of F1’s turbo era, the emphasis was much less on detailed aerodynamic progress than today – and more about engine developments. This is where the spectacular gains were to be found as the technology was still progressing rapidly thanks to advances in electronics. Automotive manufacturers such as Honda were spending colossal budgets on making these gains whereas Williams, as one of the bigger teams of the time, numbered only around 100 people. Hence, by far the most efficient way of gaining lap time was simply engineering the car around the constantly evolving engines.

READ MORE: Exploring the technological wizardry behind Williams' legendary FW15C

Williams’ technical director of the time Patrick Head recalled: “We would have an engineering meeting with Honda after each race and we’d talk through any problems we might have had and how we were going to progress.

“Then at the end of it, they would say, ‘OK, for the next race we’ll give you another 50 horsepower!’ and they were usually as good as their word.”

Patrick Head (R) seen here with Nelson Piquet, had overall responsibility for the FW11 as Williams technical director

This was a demanding time for Head, for he was effectively Team Principal and Technical Director, following the pre-season road accident that put team boss Frank Williams in a wheelchair. It would be late-season before he was able to turn up at a race.

Head and chief designer Frank Dernie had conceived the FW11 around the smaller fuel tank required for the '86 regs, giving it a lower-profile outline than the preceding FW10 (which had won the last three races of '85) and allowing the driver to be further reclined.

READ MORE: Exploring the suspension layouts that could give Mercedes and Red Bull the edge in 2020

Honda had facilitated lowering the car by giving their 80-degree V6 flatter inlet plenums – although Head continued to be irritated by Honda’s insistence on placing the oil filter below the engine, preventing him from lowering the rear deck of the car which would have given better airflow to the rear wing.

The car was constructed in carbon fibre, Williams late to the technology the previous year, four years after McLaren had introduced it. The chassis was formed as an inverted ‘U’ – with carbon fibre bulkheads, rather than aluminium as previously used – and then bonded to a carbon fibre floor. This was all done in-house at Williams’ Didcot factory.

The six-speed Hewland gearbox was mounted behind the rear axle line that put weight over the driven wheels to aid traction.

This was the first Williams to be designed using the team’s then-new CAD-CAM (computer-aided design – computer-aided manufacture) system rather than by the traditional pencil and paper and engineering drawings. This allowed for much tighter tolerances of the bodywork, which in turn made possible the slimmer proportions thanks to super-thin clearances for components.

This was long before the days of CFD and the aerodynamic surfaces of the car look incredibly simple by the standards of today, with flat, un-sculpted wing profiles, no bargeboards and no sidepod undercuts, although there was a token ‘coke bottle’ profile as the pods tapered in at the rear, an aerodynamic innovation led by McLaren a few years earlier.

READ MORE: The Lotus 79, F1's ground effect marvel

Despite the reduction in fuel tank size, the wheelbase was slightly longer than the FW10’s at just under 2800mm, fairly typical for the time. For perspective, this was almost a metre shorter than the wheelbase of a current Mercedes. The six-speed aluminium gearbox was built by Hewland to Williams’ own specifications. It was mounted behind the rear axle line, rather than in front, which is the convention today.

Turbo cars of the time tended to struggle for traction and siting the gearbox behind the axle line, where it had always been, put more weight over the driven wheels as well as making ratio changes easier. In later years, bringing the gearbox forward – a Ferrari innovation – centralised the car’s mass, gave a weight distribution better matched to the cars’ aerodynamic balance and better allowed for the extra reduction gear needed as engine speeds went stratospheric in the 1990s.

CAD-CAM software made the bodywork much slimmer, but the nose still looks wide and flat by modern standards.

There was a pushrod suspension system at the front, pullrod at the rear. The brake discs were fashioned in iron, with around 16 cooling holes drilled into their width. The tyres were Goodyear radials, as fitted to most (but not all) of the field. There was a tyre war, with Pirelli supplying the rival Benetton team.

Sliding-skirt aerodynamics had long-since been banned and underbody downforce was induced by the diffuser at the rear of the floor, the dimensions of which were not restricted at the time. No-one had yet tried the raised nose to aid the underfloor airflow and the nose of the car was quite flat and high, giving the front a look that’s bulky to modern F1 eyes.

READ MORE: Honda close to matching Mercedes on power – Verstappen

The ‘barn door’ rear wing was a visual confirmation of the vast power of the Honda 1.5-litre, twin-turbo V6. The boost of the engine could be controlled in the cockpit at the turn of a four-way knob. Setting 1 was the economy mode, 2 and 3 the usual race modes – with 4 a high-boost ‘qualifying’ setting that commanded up to 1,100bhp at 12,000rpm.

That was about as fast as engines of this size could be made to run at the time, given the limitation of mechanical valve springs, the oscillations of which would prevent them closing the valves quickly enough and cause engine failure as the piston hit the still-open valve.

READ MORE: The ground-breaking Brabham BT52

It was Renault’s innovation of pneumatic valve springs at around this time that would later pave the way for vastly increased engine speeds, peaking at 20,000rpm+ by 2006. This was years before the limits put on the number of engines used and typically the two cars would use between 50-60 engines per year, including testing.

There was a rudimentary telemetry system fitted to the car, downloading information to the garage at the end of each lap. The driver could be guided in his fuel usage by read-outs giving both consumption and remaining fuel levels.

Fuel stops were not permitted, having been banned from 1984. There was a radio link from driver to pitwall, a technology that Williams had pioneered a few years earlier.

The rear-wing is an indicator of the V6 engine's sheer power, while the massive diffuser - dimensions unrestricted at the time - produced a hefty amount of underbody downforce.

Honda had managed to increase the power of their engine despite the tighter fuel allowance with the help of fuel supplier Mobil. The F1 fuels of the time had far fewer restrictions put on them than today and were extremely chemically dense, with a high proportion of toluene which is a powerful anti-detonation agent, allowing a more aggressive ignition timing and hence greater power.

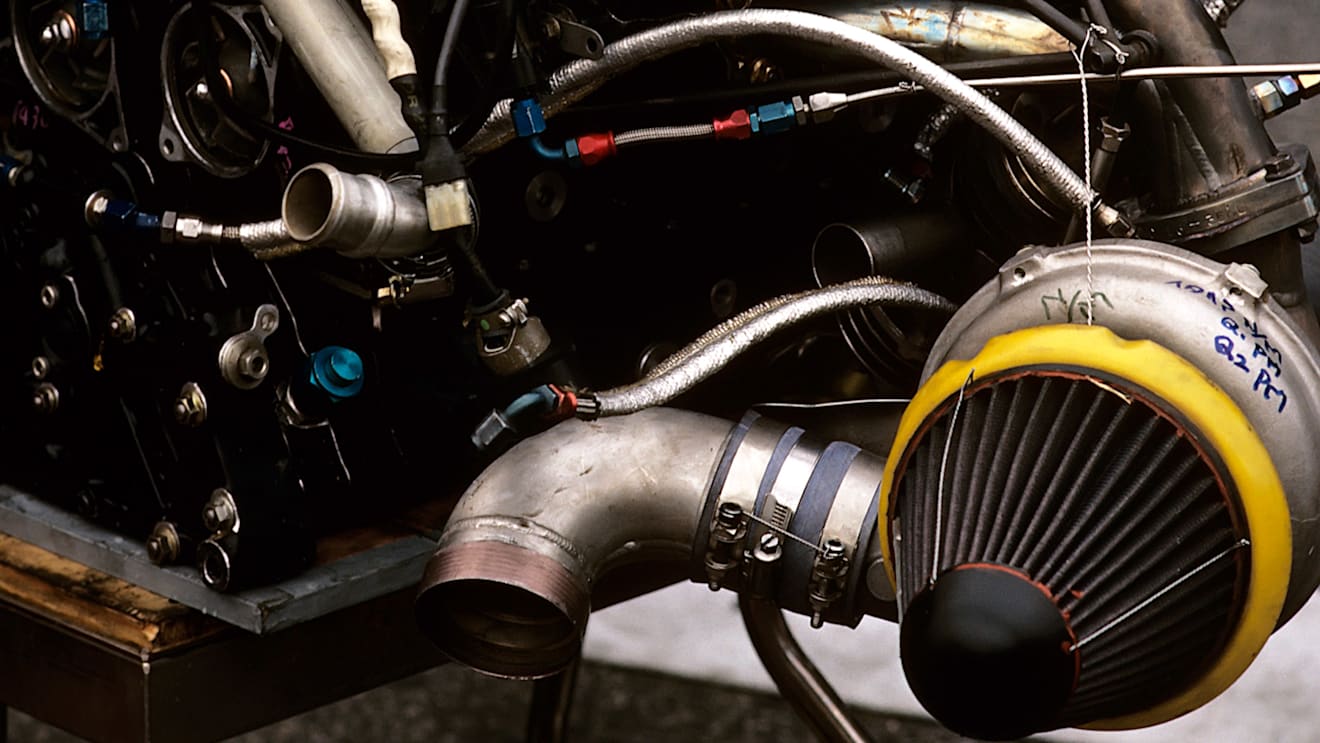

The IHI turbos featured variable geometry (banned today on the grounds of simplification and cost) so as to give different boost characteristics at different parts of the engine’s power curve.

WATCH: Top 10 – F1's cheekiest technical innovations

The fuel was fed into the cylinders at immensely high pressure to maximise its atomisation, making it more combustible. Honda had gradually reduced the cylinder bore of its engines since it entered the turbo formula in 1983, since the high boost pressures necessitated greater heat dissipation for the piston.

The engine was mounted as a structural member, in much the same way as the previous era Cosworth DFVs had been, maintaining good rigidity in the chassis while still allowing the engine to expand and contract according to temperature. This connection was as strong as that between Williams and Honda themselves in 1986, when the two were in an exclusive partnership.

From the following year, Williams no longer had exclusive access to F1’s best engine but would nonetheless carry Piquet to the world championship in a development of this iconic car.

To see this mighty car in action, don't forget to tune in on Wednesday evening to our re-run of the 1986 Australian Grand Prix - that classic title decider that saw Piquet and Mansell wrestling it around the streets of Adelaide.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked PALMER: How Oscar Piastri turned his weaknesses into strengths and became the championship favourite

News Bottas admits Cadillac ‘a very interesting project’

News Whispering Angel announced as Official Rosé of Formula 1

News Gasly ‘relieved’ as late Safety Car in Spain leads to points as Colapinto identifies key area to improve