Technical

TECH TUESDAY: Was Hamilton's Sao Paulo stampede all down to that new Mercedes engine?

Share

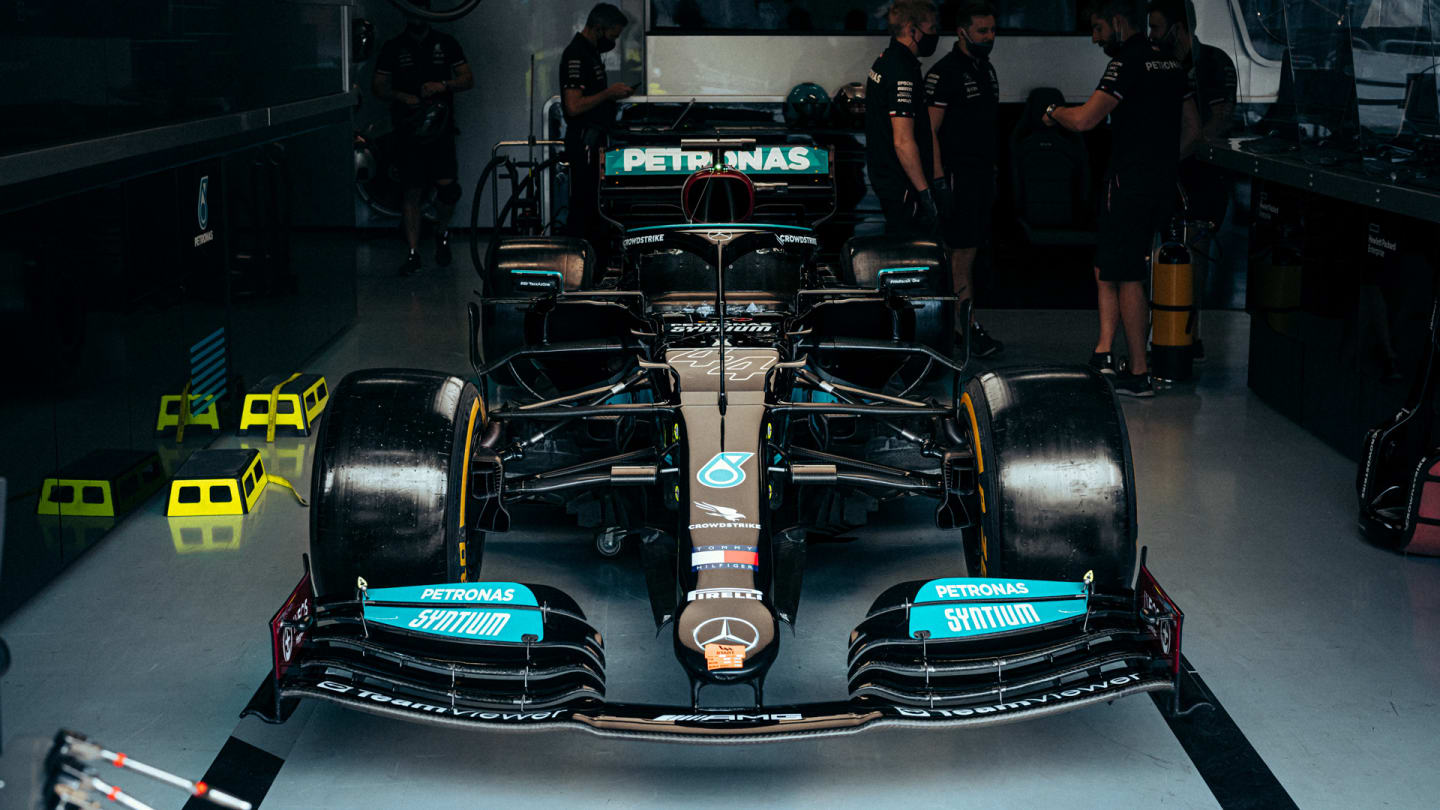

Lewis Hamilton topped qualifying in Brazil before being disqualified, then made up 15 places in the Sprint, took another grid penalty for an engine change, then made up another 10 places to win the Sao Paulo Grand Prix. So how did he do it? Mark Hughes looks at the factors that helped the Mercedes driver – with technical illustrations from Giorgio Piola.

Mercedes bounced back in spectacular fashion during the Sao Paulo Grand Prix weekend, having been outpaced by Red Bull in the previous two races. In Friday’s qualifying for the Sprint, Lewis Hamilton was fastest by a stunning 0.438s margin around a short lap over Max Verstappen’s Red Bull.

Despite then being thrown to the back of the grid in the Sprint for a DRS infringement, Hamilton was able to rise to fifth in just 24 laps. Further penalised five places on Sunday’s grid for an internal combustion engine (ICE) change, his 10th-place grid slot proved no barrier to an epic victory in the main event.

How can a turnaround in car performance be so dramatic in the seven days between the Mexico City Grand Prix and this one?

READ MORE: How some deep analysis at Mercedes HQ set Hamilton up for his brilliant Interlagos win

2021 São Paulo Grand Prix: Hamilton snatches lead from Verstappen in Brazil

New ICE

Hamilton took his fifth internal combustion engine of the season at Interlagos. As is well known, Mercedes have been carrying a reliability issue with its power units during the second half of the season, believed to centre around a materials batch issue, with cracks developing around components in the bottom end of the engine.

With Hamilton’s PU4 (introduced in Istanbul) and PU5, Mercedes believe they have largely solved that issue. But without the introduction of the fifth engine, PU4 would have been required to do all seven races since its introduction.

But another issue has arisen in that for reasons not yet fully understood the power drop-off of the new engines as they acquire mileage is much higher than expected. “We have degradation on the engine,” Toto Wolff confirmed in Sao Paulo, “and that is going to continue until the end of the season. It will continue to decrease in power… we are just seeing it creep down.”

As such the fresh engine used by Hamilton in Brazil will have given a significant step-up in power anyway, but with two power units now in Hamilton’s pool for four races it’s also quite feasible that in Brazil Mercedes chose to run PU5 with a higher mode than they would normally, so as to offset the five-place grid penalty.

Since Monza last year, whatever mode is chosen going into qualifying must then be used for the rest of the weekend. Higher modes take more from the engine life than lower ones, but the balancing point of that trade-off can be more aggressive with a new engine in the pool and not many races left.

Wolff has raised concerns about Mercedes' power drop-off while Horner has praised Honda's reliability

“One of the great things about the Honda PU,” said Red Bull’s Christian Horner, “is there is virtually no drop-off in power through its life. The difference between a new one and end-of mileage is only around 0.1s. It looks to be more than that on [the Mercedes].”

After the race Max Verstappen was talking of Hamilton’s power advantage, saying, “Taking the new engine clearly gains them a bit of performance initially – but that will slowly come back to normal. So, yeah, maybe it looks a little bit more dramatic now but I’m confident that slowly that will be a bit more normal.”

Power struggle: How Honda caught up with Mercedes – and how the Silver Arrows fought back

Hamilton was running the same big rear wing as team mate Valtteri Bottas and in their best qualifying laps in Q3 on Friday they each ran on their own in clean air, without a tow, giving a useful basis for comparison between Hamilton’s new power unit and that of Bottas, which had completed the Mexican Grand Prix weekend and which was probably running a more conservative mode.

Across the start/finish line Hamilton is sixth fastest at 323.8km/h, with Bottas 11th fastest at 320.3km/h (Verstappen is last at 316.1km/h). By the time they have reached the speed trap just before braking for Turn 1, Hamilton has found an extra 3.7km/h whereas Bottas gains only an extra 1.7km/h (Verstappen gains 2.6km/h). Ordinarily it would be expected that the car starting from a higher speed would gain less because the drag resistance squares with speed (as with the Bottas-Verstappen comparison). To gain more speed when starting from a higher speed, as Hamilton did, suggests a considerable power advantage.

Alex Brundle dissects Hamilton's extraordinary Brazil win in F1 TV's Post-Race Show

Diffuser stall

Mercedes appear to gain a lot of straight-line speed from being able to sink the rear of their car down past a certain speed threshold, as was revealed by the rearward-facing camera in Istanbul. All cars do this, but the effect is more extreme on the Mercedes.

With the loads increasing on the car as speed builds, once a certain pre-set load is reached on the straight, the car sinks down on its rear suspension, stalling the diffuser. This dumps downforce and its associated drag, increasing the straight-line speed, with the car rising back up once the speed comes back down. The speed/load threshold at which it sinks can be set through the ride height and suspension settings. This point should be set at a significantly faster speed than the fastest corner on the circuit for obvious reasons.

READ MORE: How Mercedes are trying to claw back lost downforce as the battle with Red Bull hots up

Without any truly high-speed corners and a long drag up from Juncao to the Senna Esses, Interlagos probably allows the system to work very effectively.

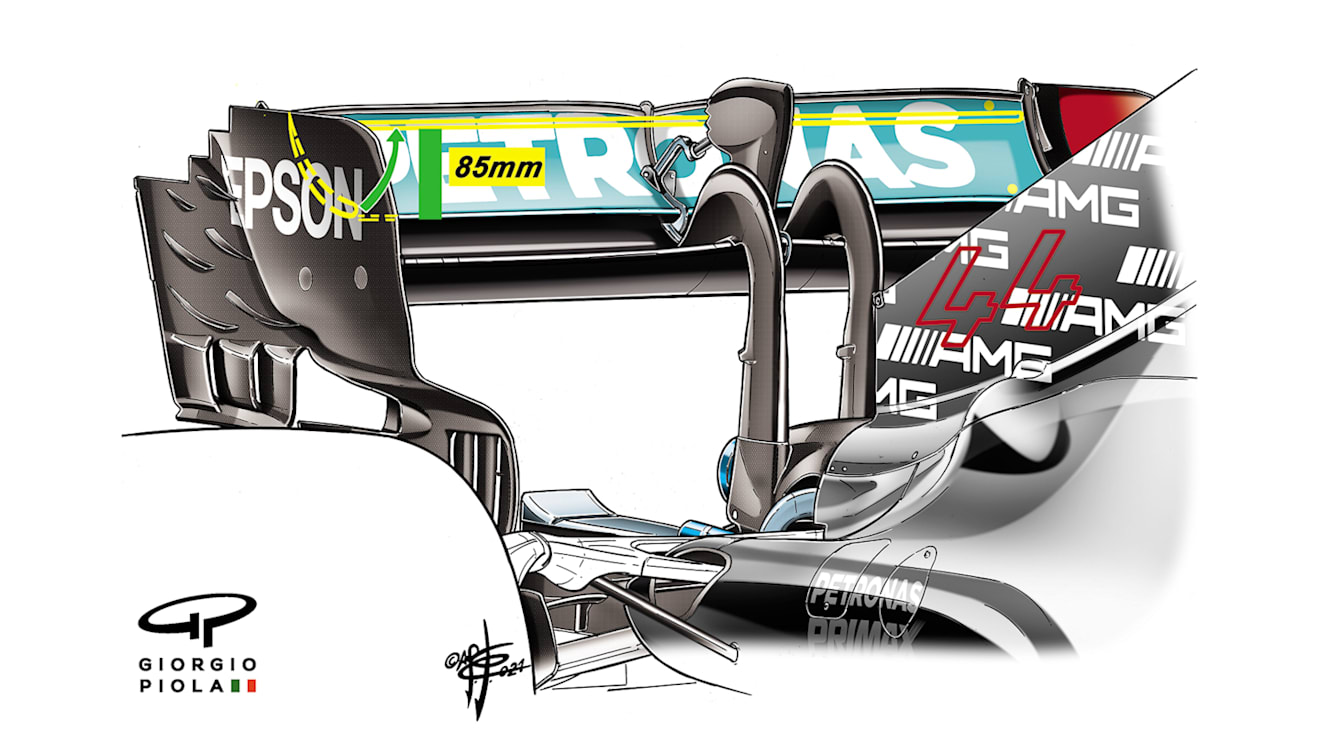

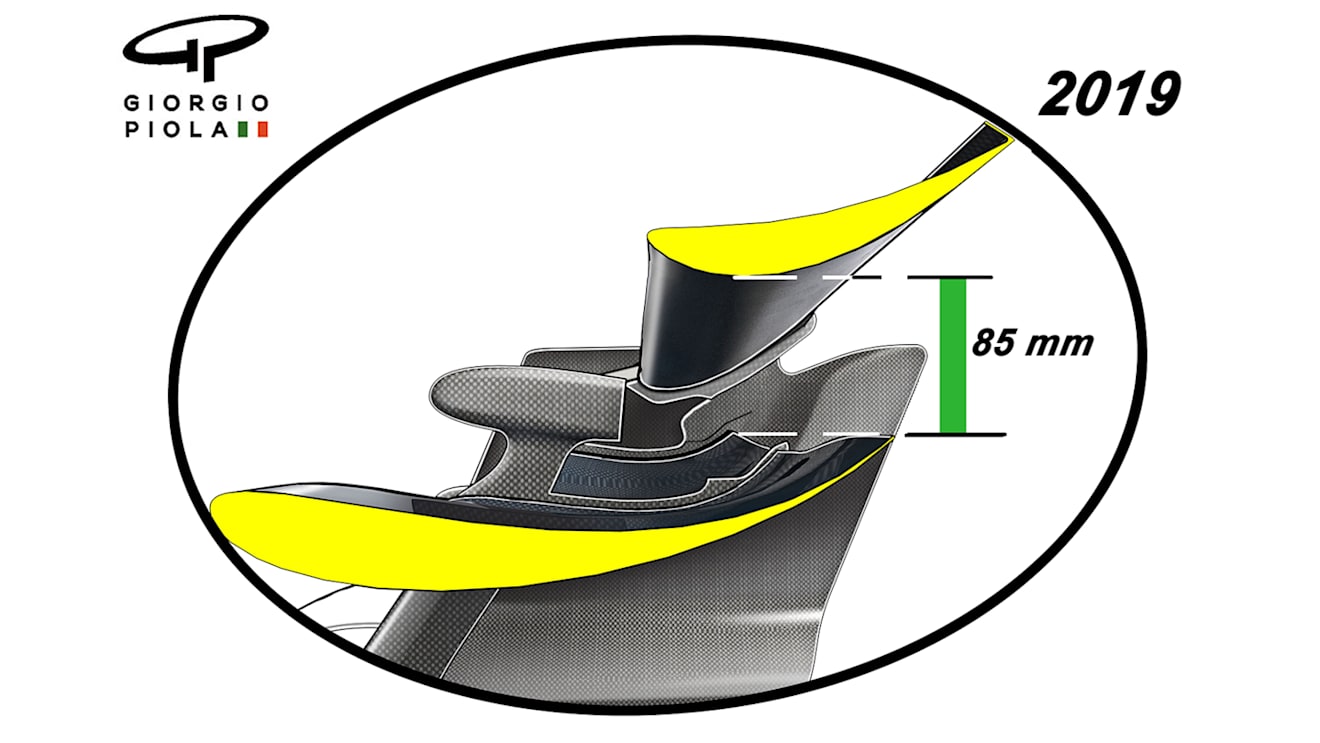

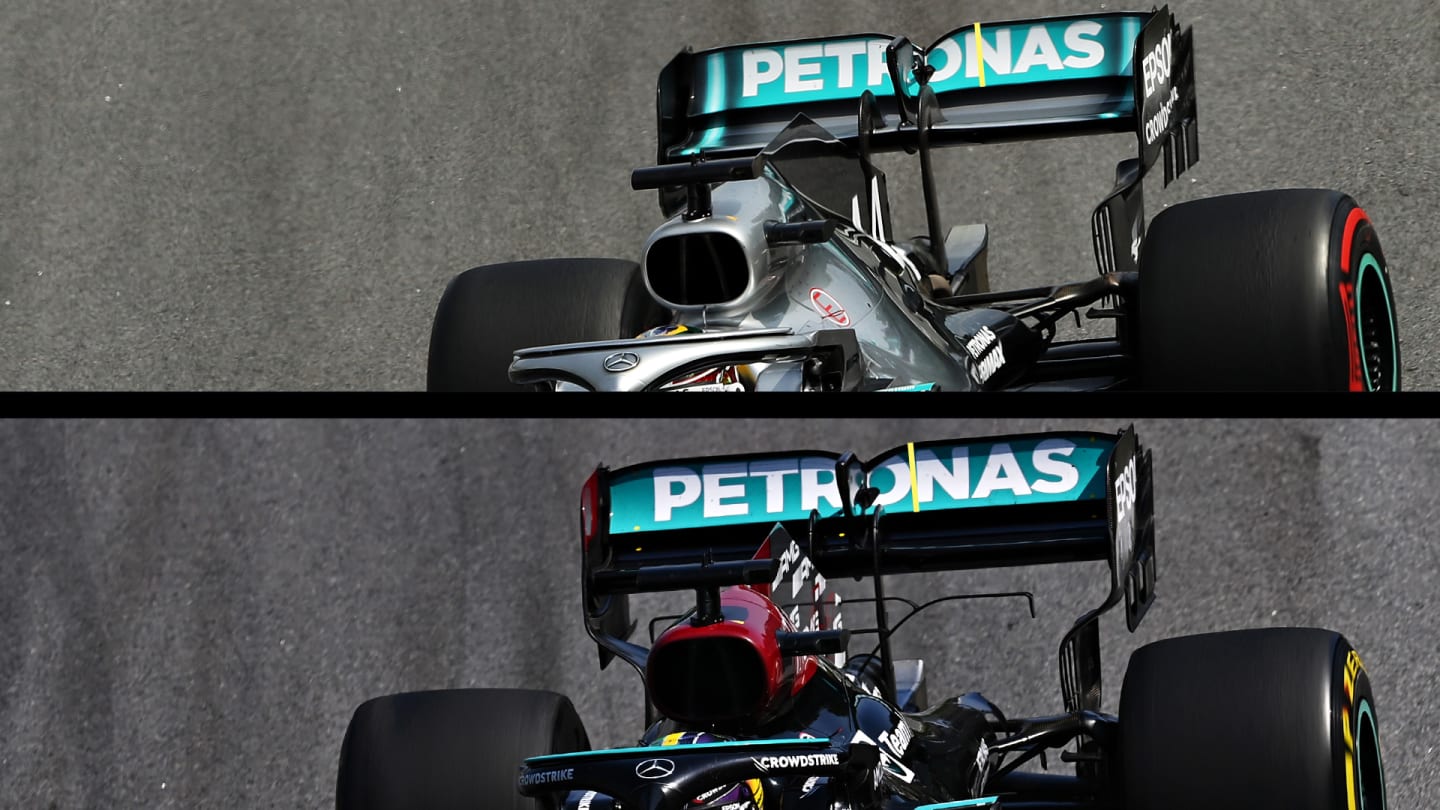

With this system helping minimise the straight-line penalty of a lot of downforce, it will enable the team to run a bigger rear wing than would otherwise be optimal. Mercedes traditionally go with a high-downforce wing at Interlagos anyway, but this year ran their high-downforce wing with its absolute maximum flap area, greater even than last time they were here, in 2019.

The marginally deeper flap used by Mercedes this year (bottom) compared to that of 2019 (top). Although essentially the same design of wing, the extra height of the flap can be seen.

This will have helped them to be so quick in the downforce-demanding sector 2 of Interlagos, where Red Bull’s high-downforce, high-rake car would normally be expected to be faster. That advantage was exaggerated in qualifying by the Red Bull overheating its front tyres through that sector and suffering understeer as a consequence.

But what the diffuser stall also facilitates is running the low-rake car with more rake and thereby gaining some of the downforce benefits of the opposing aero philosophy. The biggest performance hit the Mercedes low-rake design took with the 2021 regulation changes wasn’t the floor trim, but the the regulation limiting the length of vanes on the diffuser and the rear brake ducts. Ideally the airflow links up between those devices to make the downforce creation around the rear of the car much more effective.

READ MORE: Is Mercedes’ improved straight-line speed down to some clever ride-height engineering?

On a high-rake car, the diffuser is physically closer to the brake ducts and that airflow link-up can still be made. It is much more difficult to do that on a low-rake car.

With the diffuser stall reducing the rake on the straights, a greater angle of rake can be used on the rest of the lap, perhaps helping with that link-up between the diffuser and brake duct. On a circuit layout as favourable to the diffuser stall as Interlagos, that could explain some of the difference between the Mercedes’ speed in the previous two races to that of Brazil.

Mercedes are offsetting a supposedly negative trait of the low-rake car with diffuser stall

Rear Wing

Red Bull believe that Mercedes must have found a clever solution to the restrictions on flexible rear wings introduced earlier this season. It’s difficult to imagine what that might be, given that the cars’ bodywork must now carry markers so that any flexing of the wing will be visible to the rearward-facing camera. But what if the underside of the wing was somehow flexing?

Max Verstappen was fined €50,000 for touching the rear wing of Hamilton’s car in Parc Ferme. Asked why he had done that, he was quite frank: “I was just looking at how much the rear wing was flexing at that point. At the beginning of the season, [we had] to all change the rear wings a bit because of the back off. But it seems like something is still backing off over there [on the Mercedes]. So, that’s why I went and had a look.”

Teams will always be searching for ways around any regulation restriction with ingenious – and legal – new solutions. This may be one.

But this theory of Red Bull’s is not directly connected to the DRS discrepancy which got Hamilton thrown to the back of the sprint grid. That was because the DRS gap was found to be 0.2mm wider than the regulation 85mm at the right-hand extremity of the gap. Any effect of this on lap time would barely be measurable so goes no way to explaining Hamilton’s huge qualifying advantage.

If the DRS is worth around 0.5s of lap time at 85mm, then at 85.2 (even if the 0.2mm was uniform across the width, which it wasn’t) it would theoretically be worth 0.5001s, i.e. an extra 0.001s over a full legal lap.

1 / 2

Balance/Tyres

Mercedes found a much better set-up for Interlagos than two years ago after a fundamental rethink back at base, one which gave the car much better balance than enjoyed in Austin and Mexico and which therefore looked after the tyres better.

Some combination of power unit, diffuser stall, rear wing and chassis balance gave Hamilton a car with which he could unleash the performance which allowed him to overtake a total of 24 cars over the Sprint and Grand Prix.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked GREATEST RACES #22: Michael Schumacher seals one of his 'greatest ever' victories in atrocious conditions – 1996 Spanish Grand Prix

Podcast F1 NATION: Piastri wins in dominant style as Verstappen gets everyone talking – it’s our Spain GP review

News ‘Aggressive’ Alonso scores first points of the season at ‘special’ home race

News Briatore sets out clear Alpine target for 2026 as he shares update on search for new team boss