)

Feature

TREMAYNE: Blessed with film star looks and Grand Prix-winning speed, Patrick Tambay was above all a gentleman

Share

)

I’ve met many racing drivers who were decent guys, and a few who weren’t, but the one outstanding gentleman was always Patrick Tambay, who has died in Paris at the age of 73.

Patrick had it all: he was blessed with film star good looks and F1-standard driving ability, but on top of all that he was a thoroughly likeable man with impeccable manners, humour and honour.

READ MORE: Two-time Grand Prix winner Patrick Tambay passes away, aged 73

Only recently in his yet-to-be-published autobiography, Derek Warwick, who teamed with him at Renault in 1984 and 1985, said of him: “But if you’re talking about a great, pure person, it’s Patrick Tambay. He is a gentleman and like I’ve said, he taught me a lot about how to behave within motorsport and outside it.

“Because with him there could be times where I could honestly say that I let the shield down all the way. I always remember saying to somebody that there was only one team-mate I really trusted, so that if he said he’d just done two clicks on the dampers, I would believe him, and that was Patrick.”

Tambay raced alongside Derek Warwick at Renault

Born on June 25th, 1949, in Paris, by 1974 Patrick was a regular member of the Elf squad of drivers bound for F1 stardom, cutting his teeth in Formula 2. That season with Ecurie Elf he finished seventh, but 1975 with March Engineering saw him elevated to second overall, and he was third with Automobiles Martini in 1976.

1977 brought him the first of two CanAm championships with Carl Haas, then the disappointment of failing to qualify for his first Grand Prix with Team Surtees on home soil at Dijon. But when Teddy Yip swept him up into his Theodore Ensign N177, he responded with sixth in Germany and fifths in Holland (where he had been on target for third until he ran out of fuel with less than a lap to go) and Canada.

Ferrari had already been chasing him in Austria, but he had also impressed McLaren’s Teddy Mayer, and where Teddy was arguably wrong signing him in preference to Gilles Villeneuve – with whom Patrick was very friendly and had already raced against in Formula Atlantic – it transpired that Patrick was wrong to choose McLaren over Ferrari.

Up against a well-embedded James Hunt as team-mate, and in an outdated non-ground effect M26 in what was a generally poor year for the Woking team, his best result was fourth in Sweden. 1979 was worse, alongside John Watson, after a disillusioned Hunt had departed for Wolf.

Tambay spent two years with McLaren in 1978 and 1979

Thus he was out of F1 by 1980 as quickly as he had got into it, but he went on to win his second CanAm title and was back in the Big League in 1981, first with Theodore for whom he took sixth in the US GP West, and later Equipe Talbot Gitanes – the latter was a frustrating story, with eight retirements in eight races.

Once again it seemed his F1 career was over. He had agreed to race for Arrows in 1982 but left in disgust after the way he saw teams treating drivers during the celebrated strike at Kyalami. As a man of principle, that was not something Patrick would tolerate.

But the tragedy that took his friend Gilles at Zolder in May created a vacancy at Ferrari. He was eighth on his debut in Holland, but then third in Britain and fourth in France. And in Germany, against the backdrop of further angst for Ferrari with team-mate Didier Pironi’s career-ending shunt in practice at Hockenheim, Patrick saved the day by delivering his first F1 victory.

The following year a string of solid placings left him fourth overall, the best of them a highly charged win at Imola.

Tambay on his way to victory at Imola

He and Gilles were extremely close; when the French-Canadian had brought his family from Quebec to Europe as Ferrari beckoned in 1977, it was Patrick who had welcomed him warmly to the south of France. And Patrick once told me the story of how emotional he had been sitting on the grid in a red car bearing his departed friend’s famous number 27, and how he truly believed that Gilles drove that race for him.

“In Germany in 1982 I had felt very keenly the responsibility that rested on my shoulders,” he said, “but Imola was much, much more. By coincidence I lined up third, in the same position that Gilles had started the previous year’s race when Didier Pironi had won. Poor Gilles, he never, ever got over that. He felt so cheated!

“Right ahead of me was a Canadian Maple Leaf that the tifosi had painted on the track where Gilles had lined his car up. I felt very, very emotional thinking about him. I was sitting in my car on the grid with 20 minutes to go, and I just broke down, you know?

“I was just sitting there, crying my eyes out. I was completely broken up. My mechanics, my friends who came to the car to wish me luck, just walked away. They were embarrassed for me, and didn’t know what to do or what to say. There was nothing any of them could have done or said.”

Celebrating his second victory for Ferrari, at Imola

Eventually, the Gods smiled upon him, and after a misfire had hampered him the fortunes turned as Riccardo Patrese crashed out of the lead with six laps to run.

“I drove that race in a dream,” Patrick continued. “I don’t know if you believe in metaphysics or whatever, but I swear that wasn’t me driving that car that day. It felt as if Gilles was there with me, as if he was doing the work. All round the track there were banners saying things like ‘Gilles and Patrick – two hearts, one number!’ but I knew they were for him, not me.

“I was just driving his car, and after what happened the previous year, I desperately wanted to win this one.

“The car was beautiful that day, apart from a problem through Tamburello. In the closing stages, after Patrese crashed, it kept cutting out as I went through there, and my heart was in my mouth. I was so relieved that it kept going, but then it stopped altogether, out of fuel, on the slowing-down lap…”

HIs car ran out of fuel just after he crossed the line to take the win

It said much about his character than he was godfather to Gilles’ son Jacques, the 1997 world champion, while he was an enthusiastic supporter of his own son Adrien’s racing career.

He was overshadowed by Rene Arnoux in 1983, however, and replaced by Michele Aboreto for 1984, when he switched to Renault. That year he was quick, but often unlucky, and by 1985 Renault were a mess and both he and Warwick sank.

He decamped to Team Haas USA with little success in the Beatrice Lola THL1 and 2, with Hart and Ford power respectively, as his F1 career petered out in 1986. His 114 starts yielded those two wins, five pole positions, 11 podiums and two fastest laps.

He set up his own sports promotion company in Switzerland in 1987 before returning to racing with Silk Cut Jaguar in the World Sportscar Championship in 1989. He then dabbled in desert raids, with two top three finishes on the prestigious Paris-Dakar, and also did some ice racing and the Tour de Corse jet ski race.

Final preparations on the grid at Monaco

He had a brief dalliance with friend Gerard Larrousse’s F1 team in 1994, via another friend, businessman Michael Golay, and the Fast Group SA company they had set-up together. He made a great F1 commentator for French television, and later became deputy mayor of Le Cannet, a suburb of Cannes.

But in his later years he battled Parkinson’s disease. As ever, he did so with great valour and composure. I remember complementing him the last time we spoke, several years ago in Monaco, on just how good he was looking. “You wouldn’t have said that if you had seen me three hours ago,” he said, with a slow smile.

Always one to put on a brave face, Patrick never was a man to complain about the cards that life dealt him.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News Brown hails ‘secret weapon’ Stella as the best Team Principal in F1 amid McLaren success

News Leclerc admits double disqualification ‘hurt’ Ferrari as Hamilton left ‘100% confident’ team can fix any problems

News Tsunoda shares Red Bull’s expectations of him ahead of debut as he assesses chances of home podium

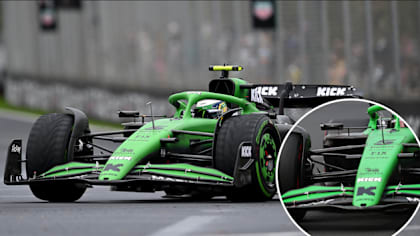

TechnicalF1 Unlocked TECH WEEKLY: Why Kick Sauber are performing much better than their pre-season testing form suggested