11 - 13 April

Feature

VOTE NOW: Most Influential Person in F1 History – the Final 4 face-off

Share

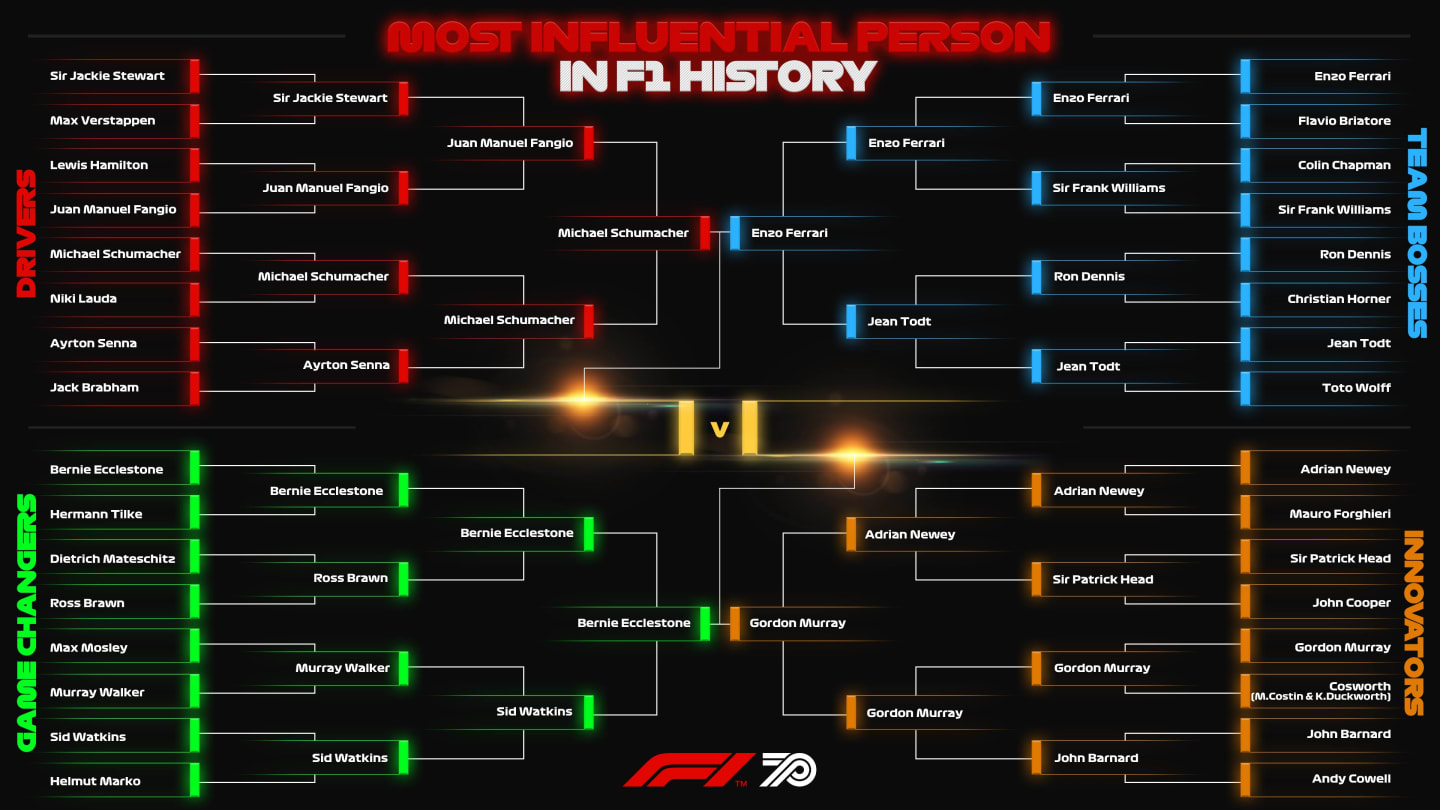

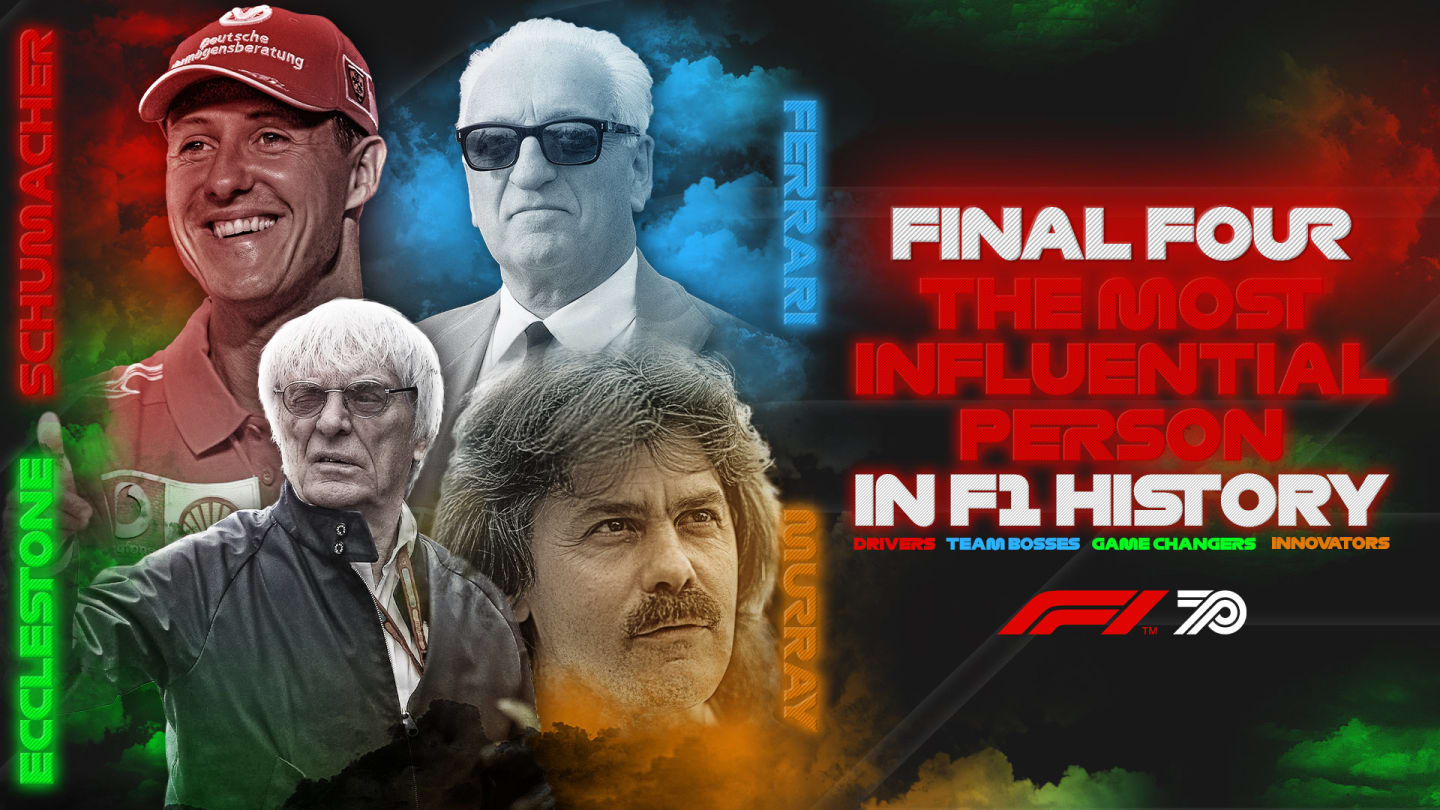

And then there were four. Yes, thanks to your votes we have already seen 28 names fall by the wayside as we continue our search for the most influential figure in Formula 1 history.

Yesterday you cast your ballots to decide on the most influential driver, team boss, innovator and game changer across the sport's 70 years. And here's how the contest looks after the latest round:

Now we have our final four, we thought we'd change things up a little. For this round we have asked four well known F1 writers to try to convince you why their candidate is worthy of your vote.

So read what they have to say, then cast your vote. We'll count them all up tomorrow when we will reveal who has made it to the final.

So let's get going...

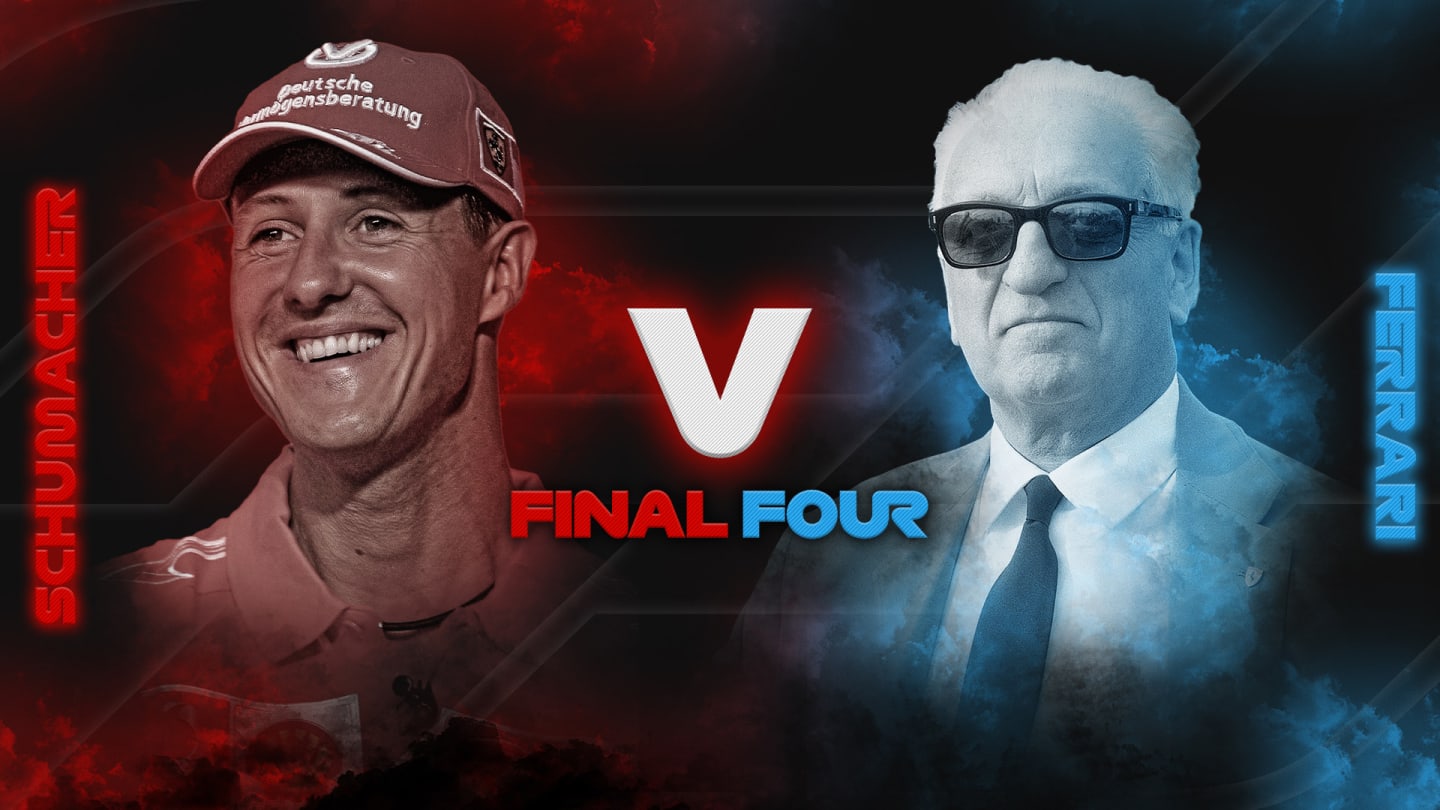

MATCH 1 – Michael Schumacher (2) Vs Enzo Ferrari (1)

F1.com's Senior Writer Lawrence Barretto makes the case for Michael Schumacher

I realise this bracket is not about success or greatness, but it is Michael Schumacher’s utter domination of a sport – with seven world titles and 91 wins – and legend that comes with it that makes him the most influential.

His ability to shatter records with alarming ruthlessness and then drag them – at the time – well out of reach gave the next generation something to aim for. He inspired them to work harder, to believe the impossible was possible. All those who have followed him into the sport are only as good because they have Schumacher’s myth to chase.

His return with Mercedes was disappointing in terms of results, sure, but he was still pushing boundaries. At over 40, to have the pace to take pole position in Monaco in a car that simply wasn’t capable of doing so, is agenda-setting. He shaped what was possible in the future, that drivers could extend their careers.

His fitness regime was pioneering, the German always looking for an edge over his rivals. At testing, he would jump out of the car between 20-25 lap runs to take a blood test for analysis. Then when he hit the gym, he would try to match those constituents in the blood. It was revolutionary, an unrivalled attention to detail.

Will Michael Schumacher be getting your vote?

He’d even take his own mobile gym to tracks so he could train between track sessions. There was no one fitter in F1, potentially even in global sport. He forced his rivals to take fitness seriously, improving not only the next generation physically but also mentally, which paid dividends in the quality of action on track.

F1 is not just about being the best driver. You need the best package. Schumacher understood that. At Benetton, he inspired a brilliant team to push harder, to be better. He then went to Ferrari, a sleeping behemoth, and did the same. He could get the best out of people. He pushed the limits. He rewrote the manual on what it takes to win in Formula 1.

In setting new standards, he ended years of pain for Ferrari’s loyal fanbase and single-handedly put F1 on the map not only in Germany but around the world. For millions – regardless of whether you have an interest in the sport – he is Formula 1.

If that is not influential, I don’t know what is.

Schumacher celebrates another win - but will he take victory in our contest?

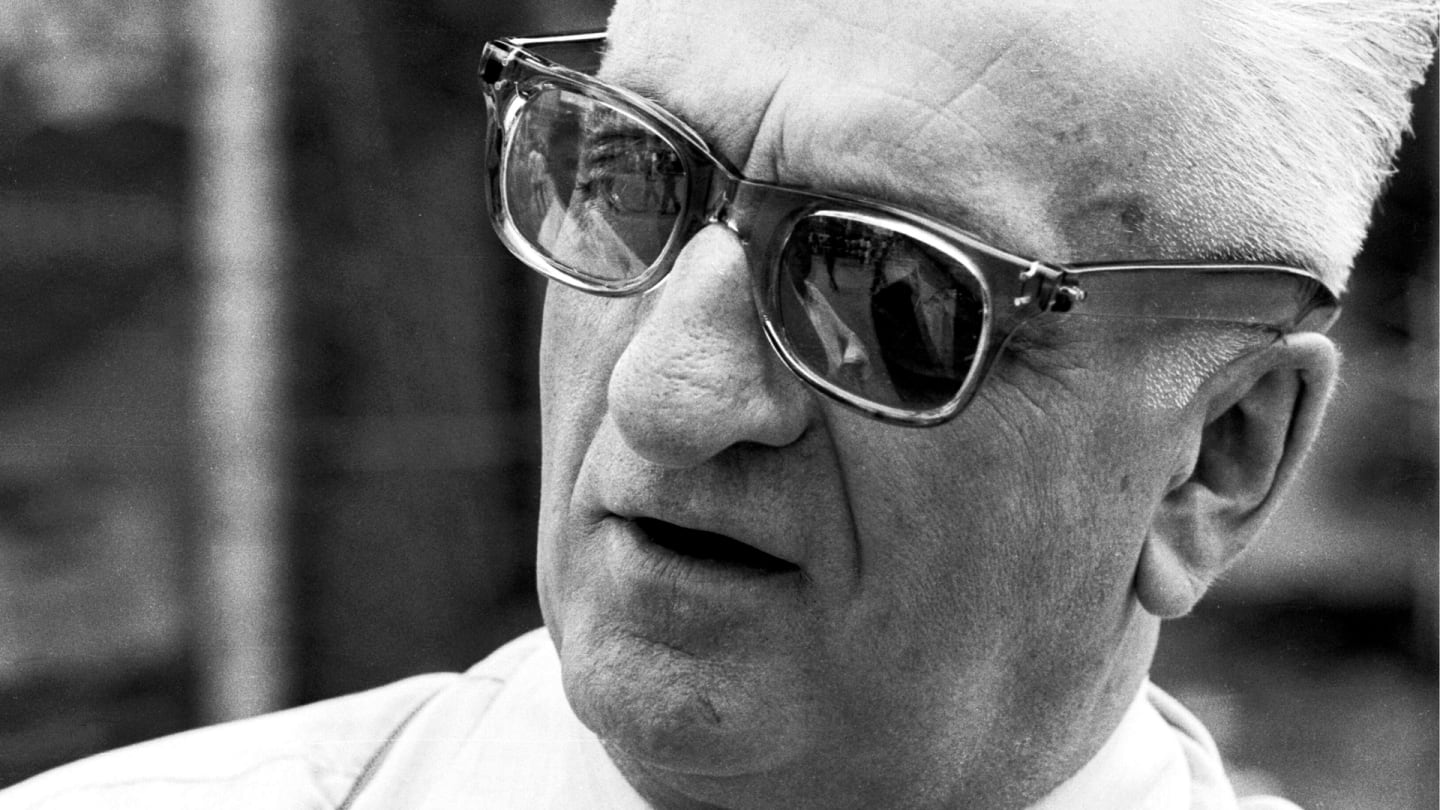

F1's Digital Presenter Will Buxton makes the case for Enzo Ferrari

Enzo Ferrari created the only team to have contested every year of the world championship. In the history of Formula 1 his team and drivers have been responsible for over 1/5 the total races won, pole positions taken and fastest laps set. His name has adorned the car which has taken a driver to the podium in more than half the races ever run.

But his influence over Formula 1 is so much more than simple statistics.

The spectre of his empire and the passion associated with its support has created a fervour inside the greatest car manufacturers on earth to enter Formula 1 in the hope they might beat him and his name.

Almost 170 have tried, and while some have succeeded, they have all tasted what it is to be bested by the name they came to beat.

The greatest innovations in the sport have come either from the fabled corridors and workshops of Maranello, or from those attempting to defeat the scarlet cars. The greatest drivers the sport has known have all either raced for or with fiery determination to try and beat the prancing horse. No other team, no other name carries such weight nor such devotion. To race for Ferrari is to be anointed by the hand of the racing Gods.

Enzo Ferrari - the man who started the team they all want to drive for

Only Bernie Ecclestone could be considered to have had anywhere near as great an impact on Formula 1 as Il Commendatore, yet even he recognised and remains adamant that Formula 1 without Ferrari would lose all meaning.

Enzo once said that if you ask a child to draw a car, they will colour it red. It was as true during his lifetime as it remains three decades after his death.

Enzo Ferrari isn’t just the most influential person in the history of Formula 1. He. His name. His team. His heart and his soul ARE Formula 1.

It is almost impossible to adequately surmise in words what Enzo Ferrari created and what his team means. It is something you feel. It is the pure emotion of racing.

Ferrari is the reason that racers race.

No matter how great their achievement, nor how meaningful their involvement over the path or direction of this sport, I cannot think of any one person in the history of Formula 1 whose spectre should merit so greatly the honour that this vote simply must bestow on Enzo Ferrari.

MATCH 2 – Bernie Ecclestone (1) Vs Gordon Murray (2)

F1 journalist Mark Hughes makes the case for Bernie Ecclestone

It’s got to be Bernie Ecclestone, the single most influential shaper of F1, the man who dragged the sport kicking and screaming onto the global commercial stage. For good or ill makes no difference; it was him.

Because he’s such a brilliant businessman it’s easy to forget that Bernie came from the sport. The sport produced him, first as an aspiring racer in the ‘50s, later as a driver manager (Stuart Lewis Evans in the ‘50s, Jochen Rindt later on) and a team owner (Brabham 1971-87).

He was involved at a granular level of the sport, understood its intricacies deeply, and combined all those experiences with his astounding negotiating skills as he became the boss of F1 and set about changing the face of the sport.

He almost single-handedly transformed it from a minority interest activity to the biggest sport on the planet, negotiating the TV deals that commercially electrified it in the ‘70s and ‘80s (while representing the teams as head of FOCA, running in parallel to his title-winning exploits with Brabham and Nelson Piquet). He banded the teams together as a single unit in negotiations with the circuits and governing body, completely overturning the balance of power.

The Ringmaster: Bernie Ecclestone has got to be a favourite to get through to the final, but will you vote for him?

In association with his one-time legal advisor Max Mosley, he went from outlaw to the establishment by way of a taste for the big stakes gamble, infiltration and the ability to bewilder his opponent in any negotiation.

He transformed the presentation and professionalism of the whole sport. He exponentially ramped up the price of being associated with F1 as it became commercially irresistible and in the process the teams leveraged their expansion upon that of the sport itself. It was Ecclestone’s overseeing the growth of the sport that made entities like McLaren, Williams and Red Bull the giants they became.

What’s often overlooked is the crucial part he played in the transformation of the sport’s safety. It is by definition a dangerous activity but he was determined that it should be rid of its gladiatorial excesses.

It was Bernie who enlisted the services of Prof Sid Watkins in the late ‘70s, Bernie who dictated to race circuits how its medical facilities were going to be exactly how Sid wanted them, who told them he would call off the race if his friend Sid wasn’t entirely happy.

He’s a disrupter, he’s mischievous, he can be very naughty. But Bernie is the biggest game changer the sport has ever seen.

Bernie, seen here with Jean-Pierre Jarier in 1976, has been in around F1 for more than half a century

Hall of Fame F1 Journalist David Tremayne makes the case for Gordon Murray

What I loved about the way Gordon Murray went about F1 design was that when it came to thinking outside the box, he didn’t care to be defined by any such prescribed structures or shapes in the first place.

Except perhaps the triangles that inspired his pyramid-section Brabham BT42 and BT44 racers of the early seventies. He was that rare creature, a genuinely open-minded free thinker who came up with ideas nobody else could.

The BT42 broke new ground with a centralised fuel tank and bluff wide nose to push air around rather than under the car, obviating lift. The BT44 and BT44B successors broke further new ground, the former with the rear suspension hung directly on the engine, the latter with a hidden vee-shaped undercar spoiler which generated a modicum of downforce. You’d never mistake any of those cars for anything else.

Gordon Murray - seen here chatting to Ayrton Senna before a race - was one of the most innovative thinkers in F1 history

Saddled with hefty Alfa Romeo engines on the BT45 from 1976, he pioneered machined aluminium bulkheads and carbon brakes, (with the latter Nelson Piquet would eventually achieve a first by winning the 1982 Brazilian GP, until he was disqualified for being underweight).

Ever keen to explore new avenues, Murray came up with surface cooling on the BT46 for 1978. Surface cooling! That was real left-field stuff! And when that didn’t quite work he and David North developed the latter’s idea for a ‘cooling’ fan to extract air from beneath the car. This resulted in the spectacularly successful and totally outrageous BT46B Fan Car, which dominated the Swedish GP.

After manufacturing Brabham’s own autoclave for a fraction of the cost of a pukka one, Murray used carbon fibre sheets in areas of the BT48, with its innovative (but unsuccessful) low-mounted rear wing, and subjected its successor, the title-winning BT49C, to the first full crash test for an F1 in 1981 after a scare at Monaco when carbon fibre splintered in a low-speed collision with a barrier.

I loved the way in which he then devised a cunning hydro-pneumatic suspension system which relied upon ground effect generated by the car’s own motion to circumvent the FIA’s ridiculous and unpoliceable rule that ground clearance had to be 6 cm at all times after sliding skirts were banned. F1 ingenuity at its best!

The Brabham BT45B 'Fan Car' was the totally outrageous brainchild of Gordon Murray

With the turbocharged BMW-engined BT50B in 1982 he pioneered in-race refuelling, which required solutions to fast wheel changing and tyre temperature control too; his answers were airguns and a tyre warming oven until tyre warmers were invented. That changed F1.

His gorgeous BT52 of 1983 boasted an arrow shape to get the best from the new flat-bottomed rules, and featured the first removable ‘race rear-end’ to speed up engine or gearbox changes.

The skateboard BT55 may have been a step too far when it re-introduced the supine driving position, but proved the inspiration for the super-successful McLaren MP4/4 which he oversaw after moving to McLaren as technical director in 1988.

The impressive thing about Gordon was that while some of his innovative ideas worked brilliantly, others were less successful, but that never stopped his stream of creativity at the forefront. And his Brabhams won 22 races and two Drivers’ World Championships for Nelson Piquet in 1981 and 1983. And the MP4/4, penned by Steve Nichols, won 15 races in 1988 and took Ayrton Senna to the first of his three crowns.

We'll reveal the winners tomorrow!

Other articles in this series

-

Introducing our knockout tournament: Who is the most influential person in F1 history?

-

Round 1 – Who is the most influential team boss in F1 history?

-

Round 1 – Who is the most influential technical innovator in F1 history?

-

Round 1 – Who is the most influential 'game changer' in F1 history?

-

Round 2 - 16 names must be reduced to 8 - but who gets your vote?

-

Quarter finals - four more names must go, but who will you vote for?

-

The final 2 are decided - who fell by the wayside at the last 4 stage?

-

Ecclestone vs Schumacher in the final of F1’s Most Influential Person contest

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News Lawson looks for positives from Racing Bulls return as race gamble 'didn’t really work'

News What is the weather forecast for the 2025 Bahrain Grand Prix?

News Vasseur admits to ‘not ideal’ start for Ferrari in 2025 and addresses ride height concerns

News ‘My Mum really cares about it’ – Antonelli on balancing F1 with schoolwork as rookie reveals his least favourite subjects