)

Feature

1950 vs 2020: Cars, drivers, safety and pit stops – how F1 has changed in 70 years

Share

)

Who could have conceived on May 13, 1950, what Formula 1 would have evolved into 70 years later? From cloth-helmeted drivers hammering around a disused airbase to the most technologically-advanced sport in the world today, we look at what’s changed – and what’s stayed the same – as Formula 1 celebrates its 70th birthday.

The cars

Let's start by looking at the car that carried Dr Giuseppe 'Nino' Farina to F1's first ever win, the Alfa Romeo 158, and comparing it to its very distant cousin, the 2020-spec Alfa Romeo C39.

1950 Alfa Romeo 158 Front-engined, rear-wheel-drive, 1.5-litre supercharged in-line eight cylinder, 709kg, 350bhp

2020 Alfa Romeo C39 Rear-engined, rear-wheel-drive, 1.6-litre V6 turbo hybrid, 746kg, 1,000+bhp

The Alfa Romeo 158 was already 13 years old by the time it lined up on the grid for the 1950 British Grand Prix, having been designed for racing in 1937 only to be mothballed during World War II.

And while the aluminium bodied, steel tubular chassis-framed 158’s power figures of around 350bhp must have looked impressive in 1950, the carbon fibre-bodied Alfa Romeo C39 that Kimi Raikkonen and Antonio Giovinazzi will compete in during the 2020 season has roughly triple the power – despite using an internal combustion engine just 0.1-litres bigger.

The Alfa Romeo 158 was already 13 years old by 1950

The hybridised 2020 car is also capable of speeds north of 220mph and able to accelerate from 0-60mph in around two seconds, compared to the 158’s time of around four seconds, and the older car’s estimated top speed of around 180mph – while compared to the 158’s aluminium drum brakes, the modern car’s carbon discs can generate a full 5g of stopping force while withstanding temperatures of up to 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Elsewhere, the eight gears on the 2020 cars are selected clutch-lessly using sequential paddle shifters on the steering wheel, while the 158 used a four-speed H-pattern box, with three pedals arranged with the accelerator in the middle (!!), clutch on the left, brake on the right.

The teams

Competitors at the 1950 British Grand Prix ranged from the two works teams of Alfa Romeo and Talbot, to the semi-pro outfits of the likes of Ecurie Belge, Officine Alfieri Maserati and Scuderia Ambrosiana, to the privateer, single-car entries of drivers like Bob Gerard, Cuth Harrison and Joe Kelly.

A mixed bag then – and it’s not like even the works teams were fielding an army of people, with footage from that first F1 race showing just a dozen or so Alfa Romeo mechanics buzzing around the four factory cars of the three ‘Fas’ – Nino Farina, Luigi Fagioli and Juan Manuel Fangio – and the solitary ‘Pa’ – Reg Parnell – while the privateers would likely have had one or maybe two mechanics spannering their cars.

Throw forward to today, and Formula 1 teams have grown into multi-million dollar-generating businesses, with staffing levels in the hundreds and, in some cases, thousands. At any one race, most teams will have over 100 staff working both at the track and remotely back at base to support the team.

The biggest F1 teams now employ thousands of people

The gear

Safety gear was a bit of a ‘whatever you fancy’ back in 1950.

Two years before the mandated use of cork helmets, Dr Farina arrived at Silverstone with his trusty cloth skull cap, two pairs of goggles (he wore the spare pair around his neck during the race), cotton overalls, leather boots and leather gloves. Some of his fellow competitors preferred the freedom of short-sleeve shirts, meanwhile…

Today, the drivers wear full-face carbon fibre helmets incorporating a Hand and Neck Support (HANS) device, flame resistant overalls, underwear, driving boots and gloves – while since 2019, those gloves have been fitted with biometric technology relaying real-time information about the drivers’ pulse and blood oxygen levels back to race control.

1 / 2

The track – Silverstone

Having been opened as an airbase in 1943 during hostilities, the layout of Silverstone as used for the 1950 British Grand Prix was essentially a lap of the perimeter road of the aerodrome (it’s called ‘Hangar Straight’ for a reason) with the race beginning on the now-disused Farm Straight, before the drivers tackled the first right-hand corner at Woodcote and set off around the rest of the sweeping, fast 2.987-mile lap.

The competitors tackled Woodcote first in 1950

Facilities-wise, creature comforts were in short supply, with mechanics having to work on the cars parked on the grass behind the pits, or in the pit lane itself – where the only thing to protect them from a car passing by at 150mph was a painted white line…

While the five key points of the 1950 track remain today – Woodcote, Copse, Becketts, Stowe and Club – the circuit has swollen to 3.660 miles since its 2010 reconfiguration, while in 2011, it gained its distinctive Wing building, housing state-of-the-art facilities and sitting on top of the new pits, with Abbey – a lap-ending left-hander in 1950 – a lap-starting right-hander now.

WATCH: Take a lap of the modern Silverstone with Lewis Hamilton

The drivers now tackle Abbey first

The drivers

Look at footage of the 1950 British Grand Prix and you can’t help but notice one thing: the drivers are pretty old! The average age of the racers that day was 39, while Luigi Fagioli, Louis Chiron and Philippe Etancelin were in their 50s. At 29, Geoffrey Crossley was the spring chicken of the bunch – and he was older than 13 of the 20 drivers on the current grid.

They were a pretty rag-tag lot as well, a mixture of rich aristocrats like Prince Bira and Swiss racer Baron de Graffenried, a doctor of political science in Farina and even a Belgian jazz band leader, in Johnny Claes.

READ MORE: 10 fascinating facts about the very first F1 race

Racers included Thailand's Prince Bira

There isn’t really room for such charming part-time-ism in F1 these days. Instead, all of today’s drivers began competing in karting at a young age (Williams’ Nicholas Latifi is considered a late starter, having begun racing at 13), while all have followed conventional routes to get the top of the motorsports ladder via various junior formulas. The average age of the current grid stands at 26, with Raikkonen as the oldest driver at 40 – and Lando Norris the youngest at just 20.

At 20, Lando Norris is the youngest driver on the current grid

The competition

The amateurish nature of that first race, plus the varying quality of the machinery, understandably gave rise to some wildly diverging performances.

Farina’s pole position was set at 1m 50.8s (94.4mph) – while Johnny Claes qualified last, precisely 18 seconds (that's right, 18 seconds) off the Italian’s pace. The race, which lasted 2 hours and 13 minutes, then saw 10 of the 21 starters retire, while eight of the 11 finishers had been lapped by the race end – three of them finishing six laps down on winner Farina.

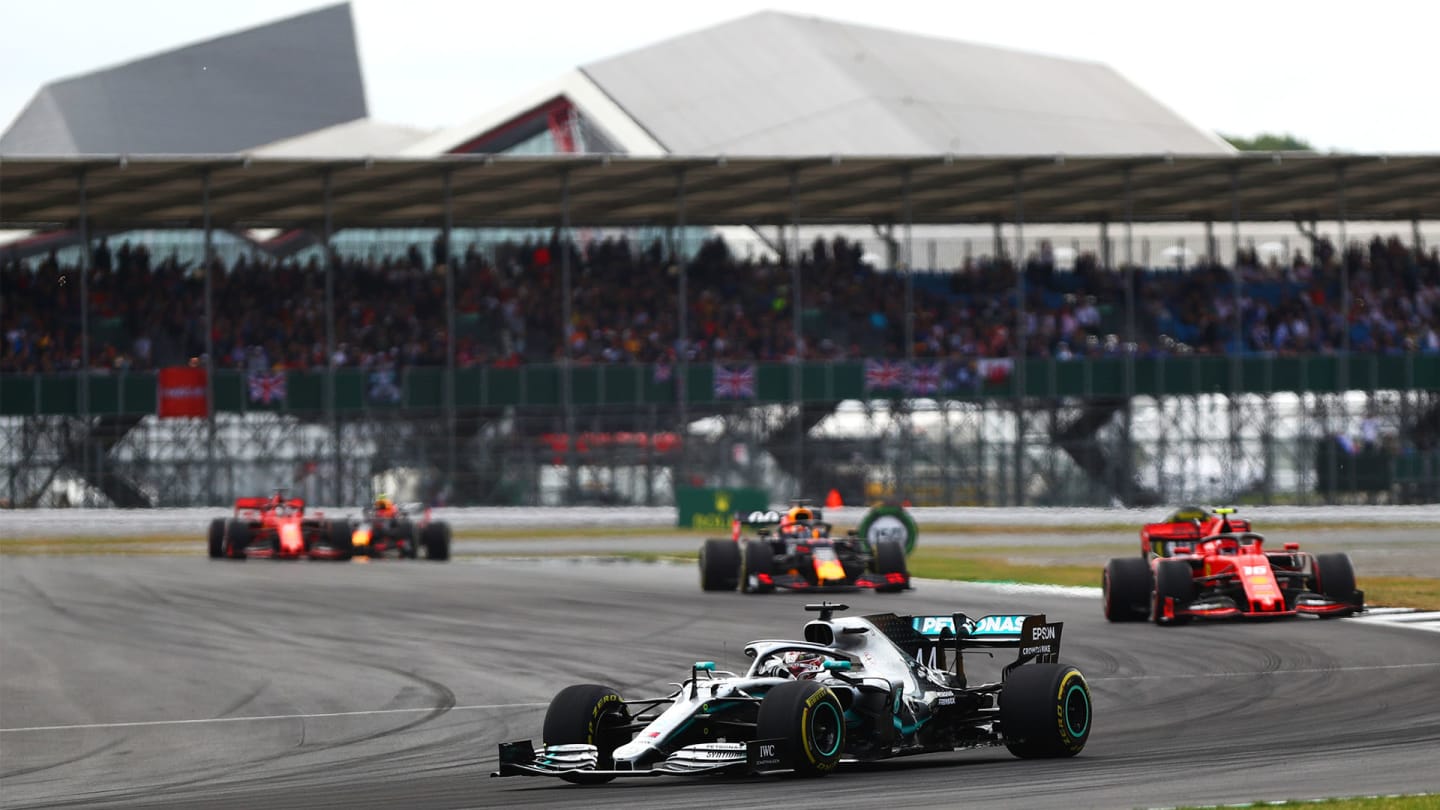

Compare that to the 2019 British Grand Prix, and the gap from Valtteri Bottas’ pole position (set on the modern circuit at an average speed of 155.7mph) to the back of the pack was just 3.164s – while in the one hour 21 minute race, there were just three retirements, with all but three classified drivers finishing on the same lap as winner Lewis Hamilton.

READ MORE: Check out the full results from the 1950 British Grand Prix

The competition is much closer nowadays

The points

For all Farina’s hard work, the Italian was handed a measly eight points for victory in the Grand Prix de Europe/British Grand Prix (the same race, confusingly), plus a point for fastest lap, with the top five scoring points on an 8-6-4-3-2 basis. A driver’s four best scores for the season counted towards the drivers’ championship, while there wouldn’t be a constructors’ championship until 1958…

Hamilton’s 2019 Silverstone win, meanwhile, bagged him 25 points, plus an extra one for fastest lap, with the top 10 currently scoring on the following system: 25-18-15-12-10-8-6-4-2-1.

READ MORE: Find out more about F1's first champion, Nino Farina, in our Hall of Fame

The pit stops

Pit stops for fuel and tyre changes were a leisurely affair in 1950. “The Alfas refuelled slickly,” Motor Sport Magazine’s report from the race ran, “Fangio’s, Fagioli’s and Farina’s taking 25 sec., Parnell’s 30 sec.”…

Today, a pit stop for a tyre change – refuelling was canned at the end of 2009 – is slow if it takes three seconds or more, with Red Bull Racing holding the current pit stop record, for changing all four tyres on Max Verstappen’s car in 1.82s at the 2019 Brazilian Grand Prix. The size of the crews has grown, too, with around 20 people working balletically to service the cars during a stop these days.

Safety

With the Silverstone circuit lined with hay bales and flower-topped oil drums in 1950, and most of the drivers racing helmet-less and seat belt-less (better to be thrown out than burnt, as Stirling Moss always chillingly reasoned) safety was clearly not top of the to-do list at F1's first race.

Sadly, it took successive deaths and career-ending crashes in Formula 1 for people to get really serious about safety. But get serious they did, with the result that today, F1 drivers race at tracks equipped with hospital-grade medical facilities, medical evacuation helicopters, circuits with sufficient run-off areas, marshals trained in driver extraction, and a dedicated medical team who travel to every race.

READ MORE: Driving the F1 Medical Car – the world’s fastest ambulance

Car-wise, today the drivers are held in by six-point racing harnesses, while in addition to both a super-strong roll and crash structure, the cars also feature halo devices (introduced in 2018) as well as a warning system that illuminates if a crash registers a 15g lateral force, or a 20g vertical one, for more than five milliseconds.

Fortunately, the chances of a driver surviving a crash like this are much higher today

And what’s stayed the same…

Despite the chasm of difference between Formula 1 as it was on May 13, 1950 and how it is today, some things about the sport will never change.

Ultimately, the competition remains about one driver trying to beat another, both in the 'putting it all on the line' banzai attack of qualifying and the more considered 'chess match' that is the race – although with the 2020 season originally slated for 22 races (compared to just seven in 1950), more money involved, a constructors’ championship to consider, plus cars that are far more robust mechanically and in terms of safety, there’s no doubt that the complexion of both a Formula 1 race and season has shifted...

Apart from the shared spirit of competition, though, some names from that 1950 season remain in F1 too, with the Alfa Romeo brand having returned to the sport in 2019, while Farina’s victory at Silverstone came on Pirelli tyres, just as Hamilton’s did last year.

Ferrari joined the F1 party later in 1950, and have been there ever since

F1’s most famous name, Ferrari, would join the 1950 grid at the season’s following race in Monaco, while then, as today, both they and Alfa Romeo would use Shell oil – while Castrol, who today supply lubricants for Renault, were supplying them for Ecurie Belge on race day at Silverstone in 1950.

So, Formula 1 at 70 – the same and yet so, so different. Here’s to the next 70 years…

More on F1's 70th anniversary

- 10 fascinating facts about the very first F1 Grand Prix

- PODCAST: Listen to Martin Brundle discuss the best cars he's driven from every decade of F1

- Under the bodywork of the Alfa Romeo ‘Alfetta’ – 70 years after it won the first ever F1 race

- Why is it called Formula 1 – and 12 other questions about the championship’s origins

- 1950 vs 2020: Cars, drivers, safety and pitstops – how F1 has changed in 70 years

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Report F2: Lindblad dominates in Barcelona to claim Feature Race victory for Campos Racing

News Hulkenberg reveals ‘golden ticket’ that helped him secure impressive P5 in Spanish GP

Video WATCH: See how Piastri beat McLaren team mate Norris to pole with our ‘Ghost Car’ feature

News DRIVER OF THE DAY: Verstappen's battling Barcelona drive earns your vote