)

Feature

An innovator and trendsetter – Adrian Newey's greatest F1 contributions

Share

)

When Adrian Newey first came into Formula 1 with Fittipaldi as what he called “junior aerodynamicist but what turned out to be senior aerodynamicist” in July 1979, not even the man himself could have envisaged how profound an impact he would have on Grand Prix racing.

Forty-five years later, he’s still driving innovation in an arena where he, more than anybody else in that timespan, has defined the breed.

Innovation takes many forms. Most obviously, it’s about originating a brand-new idea that can be integrated into a car to bolster performance, but it can also be about applying existing technologies in a new way.

It might not even be about a specific item, but instead lie in razor-sharp interpretation of the regulations or original conceptual thinking that radically redefines the balance of the countless compromises in any design. Newey has been responsible for numerous examples of such innovation, with some of his key ideas setting the trend for modern F1 machinery.

)

Adrian Newey has been a pivotal figure through his F1 career

1988 – F1’s aerodynamic template

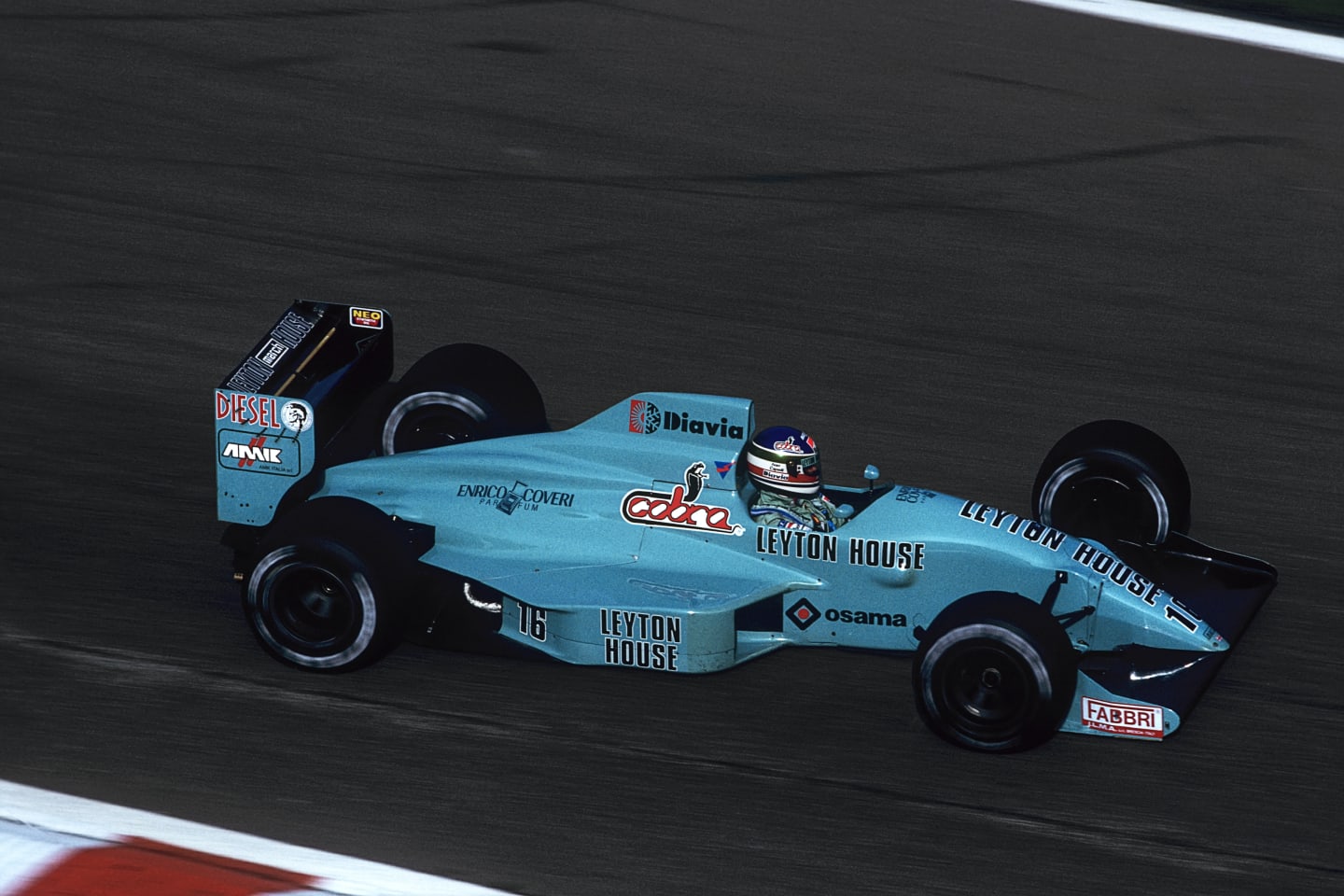

The March 881 never won a Grand Prix, but it is effectively the prototype for the aerodynamically-driven F1 that followed. In the mid-1980s, F1 was dominated by bulky, bloated machines designed to package the potent turbocharged engines with aerodynamics taking a back seat. While the ‘lowline’ McLaren-Honda MP4/4 is celebrated to this day also tackled that trend and dominated the season, Newey’s design is the more significant car.

Knowing that March was running not only a normally-aspirated engine, but also an underpowered Judd unit putting out around 580bhp, the car had to be aerodynamically efficient to have any chance. Newey therefore focused on producing a lightweight, compact car with a small cockpit – for drivers Ivan Capelli and Mauricio Gugelmin too cramped – and tight aerodynamic packaging.

The key change was the full-integrated nose/front wing assembly, combined with an undercut shape on the bottom of the nose behind it. Before that, the convention was to have two separate flaps and a more bulky nose that extended forward of and below the wing plane.

This had several benefits. Firstly, by making the front wing span the full width of the car it created the maximum downforce. Secondly, it ensured clean airflow beneath the wing and therefore to the floor. Thirdly, the low-pressure created by the undercut space below the nose helped to pull the airflow over the wing and increased the downforce created.

Effectively, this was the start of the raised nose era in terms of the conceptual objectives, even though the nose of the March itself was flat. What’s more, Newey also began the trend for more complex ‘three-dimensional’ endplates with this car, as they previously were generally flatter.

While the March 881 never won a grand prix, it is effectively the prototype for the aerodynamically-driven F1 that followed

1988 onwards – Seating position

The driver is the most awkward component to package inside the car and over the years Newey more than anyone was key in evolving the current seating position. Starting with the compact packaging of the March/Leyton House cars, which Newey himself later admitted was too extreme at times, he pushed what was possible with the cockpit configuration.

Newey worked to optimise this in the late 1980s and mid-1990s whereby he set the model for the feet and pedals to be significantly higher than where the driver actually sat, meaning the seating position became increasingly reclined over the years. This had multiple advantages as by having the driver reclined with arched back, it lowered the driver’s head for aerodynamic advantage.

The centre of gravity was also lowered and there were packaging advantages when it came to the steering column position. What’s more, the raised feet/legs meant more space for the high nose design to be optimised to maximise the airflow underneath the car.

This evolution effectively defined the seating position still used today, albeit with ongoing optimisation to maximise the benefits.

1992 – Active suspension

Newey was neither the first to dream up active suspension, which was pioneered in the automotive industry, nor its F1 pioneer as that was Lotus as early as 1983. He didn’t even develop the technology of the active suspension system that was an integral part of the Williams FW14B and its successor, the FW15C.

What he did do was to harness the full potential of active ride when it came to aerodynamic opportunity, having recognised the potential of it in his Leyton House days and started an in-house programme there.

Williams itself had run active ride as early as 1987, but what Newey recognised was the full extent of its value aerodynamically. He saw it primarily as a platform control device that would allow aerodynamic surfaces to be driven harder thanks to the ability to keep the car in a narrower window. He also hit on the idea of dropping the rear of the car on the straight to reduce drag at the push of a button, improving straightline performance.

Adrian Newey pictured in 1993 alongside Alain Prost during his time at Williams

1995 – Undercut diffuser

This was a key advantage of the 1996 Williams, but first appeared late in 1995 on the Williams FW17B. Newey recognised it was possible thanks to the floor regulations that introduced the ‘step plane’ towards the rear of the car.

While the diffuser was restricted in size by the rules, there was no obligation for bodywork on the step plane to extend all the way to the rear of the car. This made it possible to create a larger diffuser exit by effectively sweeping the diffuser upwards behind the rear wheels so its exit was positioned higher even than the exhausts.

This created a major downforce-generation advantage that was optimised for 1996.

1996 – Cockpit sides

Regulation changes for 1996, inspired by accidents such as the one that left Karl Wendlinger in a coma at Monaco in ‘94, meant protection of the driver’s head was improved by the cockpit sides being raised and increased headrest padding being mandated.

But while the most literal interpretations of the rules led to bulky designs such as John Barnard’s Ferrari F130 that resembled an armchair and the similarly cumbersome Benetton B196 , Newey had other ideas. The result was a classic example of spotting loopholes in the regulations.

The rules specified 75mm thick Kevlar-coated foam headrests along with a minimum chassis height. Newey recognised you could lower the headrests and then add a thin piece of bodywork that satisfied the regulations.

This reduced the blockage around the cockpit and therefore ensured better airflow to the back of the car. Unsurprisingly, this design became the template in 1997 when rivals could produce new monocoques to make the most of the concept.

What makes Adrian Newey so good?

1998 – Narrow track car concept

Newey is renowned as a master of rule changes and that’s exemplified by the McLaren MP4-13 of 1998, with which he made several key decisions that set the direction for the cars of this era. A key part of that was recognising the need for a long wheelbase both to maximise the aerodynamic opportunity – a trend that continues to this day – and to create diagonal stability characteristics that weren’t dramatically different from the 1997 car.

Newey also pushed to get the centre of gravity as low as possible, hence the lowline chassis that contributed to improving the stability of the car for the new grooved tyres. The car also featured brake steer, until it was outlawed, although that was a concept conceived by Steve Nichols before Newey arrived.

2009 – Pullrod rear suspension

This is another example of something that Newey didn’t invent, as pullrod suspension configurations were well known. But he did kickstart a period where pullrod rear suspension became the norm. To achieve this, it required a complete repackaging of the rear end around the regulation changes that limited the height of the diffuser.

This meant a premium on ensuring that the low pressure era at the exit of the diffuser was maximised and that the airflow at the rear of the car was optimised. Whereas the pullrod had been a disadvantage under the old rules, it worked well for the new regulations.

While Newey ‘missed’ the double diffuser loophole in 2009 – although it’s worth noting it’s a geometry that was looked at but rejected because it was impossible to feed it with the necessary airflow to make it work legally in his view – the overall concept of the 2009 Red Bull was best suited to the new rules.

The overall concept of the 2009 Red Bull was best suited to the new rules

2010 – Exhaust-blown diffuser

Using the gasflow exiting the exhaust to blow the diffuser and create downforce had been done before, with Renault conducting the first experiments in 1983, but Newey, ‘re-invented’ this in 2010 with the Red Bull RB6. Newey had worked on exhaust-blown diffuser cars before, notably the Williams-Renault FW14B, but in a form that was subsequently outlawed by the requirement for any sprung part of the car visible from directly beneath the car to lie on one plane. The emergence of the double diffuser in 2009, which created the opportunity to blow the upper part of the diffuser from the side.

Newey’s first port of call was engine supplier Renault, which he urged to dig out the work done with Williams on the engine modes needed to optimise exhaust blowing in the early ‘90s. Renault quickly became adept at finding ways to run the engine not only to produce power but also act as a glorified air pump. Not only did star driver Sebastian Vettel master the counter-intuitive driving style required, but Red Bull and Renault made significant progress in off-throttle exhaust blowing – both for ‘cold blowing’ whereby the throttles stayed open with the fuel and spark cut – and later for ‘hot blowing’ whereby the ignition was retarded and fuel fired into the exhaust, igniting to energise the airflow.

Successive regulation changes attempted to curb this, but Newey and Red Bull were able to continue to find ways to use exhaust blowing to energise the floor and the exhaust, albeit with increasingly modest returns because of the rules.

2022 – New ground-effect template

With F1’s regulations becoming ever more restrictive, much to Newey’s displeasure, F1 is now less about new ideas and more about wider conceptual thinking. The reintroduction of full-blown ground effect venturi cars in 2022 allowed Newey once again to set the tone.

Where Newey was key was with his previous experience of ground-effect racing cars and in understanding the need to integrate the aerodynamic and mechanical characteristics. He fed key ideas into the concept of the Red Bull and personally designed the front and rear suspension.

With platform control a crucial demand of today’s cars and the recognition that simply being seduced by the massive downforce figures a ground-effect floor could create, Newey recognised it was about ensuring such performance could be dependably delivered without hitting bouncing and porpoising problems.

Combined with the rounded shape of the chassis that allowed space for the venturis to be made more powerful – something that has subsequently been made more pronounced, this meant Red Bull was one step ahead of its rivals from the start of the current rules era.

Share

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Podcast F1 EXPLAINS: Legendary F1 racer Mika Hakkinen answers listeners’ questions live at the Monaco Grand Prix

Video HIGHLIGHTS: Watch the action from FP1 in Spain as Norris sets early pace over Verstappen

News FIA Team Principals press conference – Spain

News F1 25 out now – with 'F1' movie integration and the return of ‘Braking Point’ story mode