30 May - 01 June

Interview

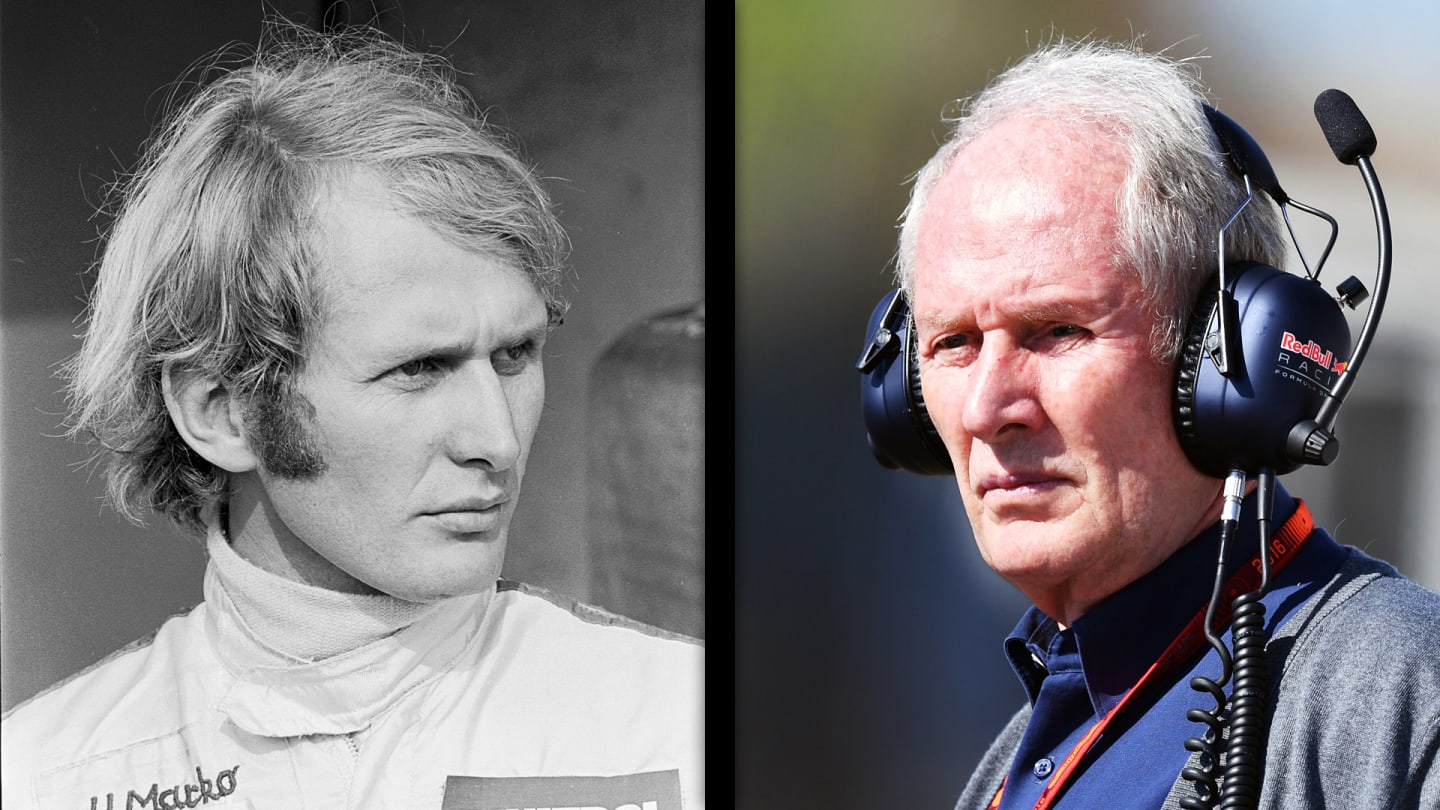

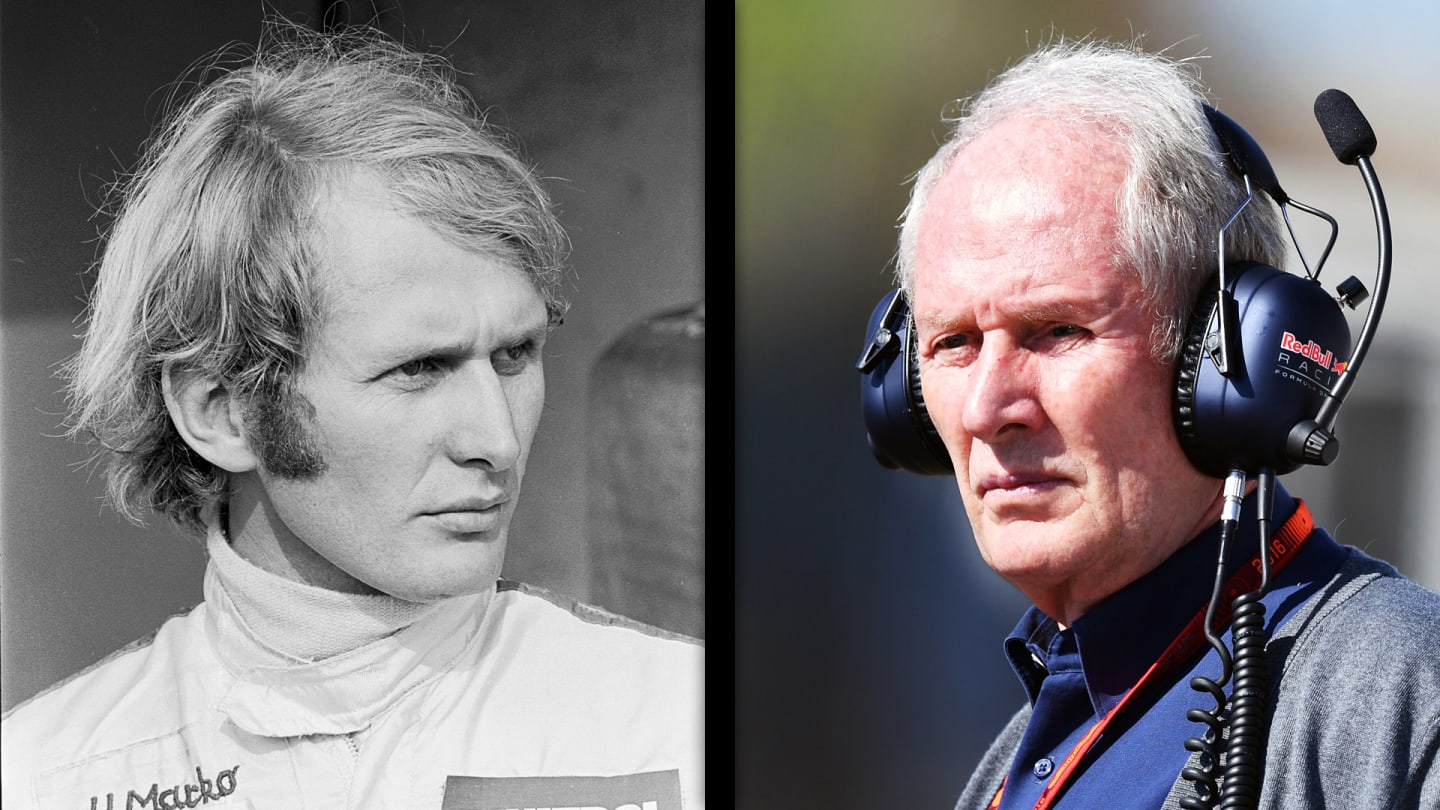

From rising F1 talent to F1 talent spotter - the Helmut Marko story

Share

Today Helmut Marko is an ever present in the F1 paddock; a man with a well-earned reputation for identifying, nurturing and promoting some of the best drivers on the grid, including Sebastian Vettel, Daniel Ricciardo and Max Verstappen. But did you know that Red Bull's motorsport advisor was once a highly-rated young F1 driver himself, one who, were it not for a cruel twist of fate, some believe might have gone on to greatness? We sat down with Marko ahead of his home race to discuss the part of his career unknown to many…

"We drove all night to Nurburgring. We parked in the woods, slept in the car and woke up the next morning to the noise of F1 cars" - Marko on his first F1 experience, Germany 1961

Helmut, you were good friends with Jochen Rindt as a young man; you grew up together, had some of your first experiences behind the wheel of a car together and went to watch races together. Is that correct?

Helmut Marko: Yes, that’s how it was. And it really was! (Laughs) The first race we visited was Nurburgring in 1961. We both had failed our university entrance diploma and instead of going home and telling the sobering news decided to go to a race. We drove all night to Nürburgring. We parked in the woods and slept in the car and woke up the next morning from the noise of the Formula 1 cars. Jochen immediately said: ‘That’s for me, that is what I want to do!’ We were sitting devotedly in the grass listening to the sound of the cars and after a few laps were able to say whether it was a Ferrari passing or a Matra or a Cosworth-powered car. I was 18 and Jochen was 19.

Is it fair to say that without Jochen you wouldn’t have started racing? Or were you always destined to race?

HM: Jochen infected me with the racing bug. We both were always interested in racing, but didn’t have the self-confidence. But then Jochen went to England and succeeded - so I thought: ‘If he can do it, I can do it too! Why not?’ But I and all the Austrian drivers that followed him have to be very thankful, as without him none of us would have broken into the sport so easily. He paved the way.

Back then we didn’t recognise how dangerous F1 really was. You were bloody lucky if you survived! - Helmut Marko on driving in F1 in the 1970s

Without that racing bug, what would your future have looked like? A nine-to-five job as a lawyer?

HM: Nine-to-five sounds terrible. But yes, I would have pursued a career as a lawyer. Very likely a commercial lawyer. But I am happy with how my life went – and happy that I have survived – even if I’m a bit damaged [Marko lost his left eye when a stone went through his visor during the 1972 French Grand Prix]. Back then we didn’t recognise how dangerous F1 really was. We had a kind of self-deception, saying that you were unlucky if something happened to you – but it was the contrary: you were bloody lucky if you survived.

Your ascent up the racing ladder seemed very swift - if not quite as swift as Max Verstappen’s! There wasn’t long between you racing a Formula Vee and racing a Porsche 908 at Le Mans…

HM: To be honest I cannot remember. All I remember was that I already earned money in my first year of racing professionally. The fact is I was racing everything I could lay my hands on: saloon cars, prototypes, and Formula 2 cars - whatever was available. What I remember about Formula Vee was that I started in Monaco in 1967 and won the race. My first F1 race was then in 1971.

Was your aim from the beginning to reach F1?

HM: Yes. If you start a professional racing career it is the natural aim. Especially when I saw how high the level in F1 is. You simply wanted to be one of them.

"It was on my debut I realised how difficult these cars were to drive. It took me quite a while to push the car to the limit..." - Marko (second car) on his F1 debut in Austria in 1971

And of course you won at Le Mans in the biggest beast of them all, the Porsche 917. You wouldn’t have been happy just sticking with those kind of cars?

HM: F1 was always the goal. But besides Jackie Stewart all the other drivers were driving sportscars and Formula 1. But it’s true: the 917 was a real challenge. And to get a bit of the memory back I will drive it this year at the Austrian Grand Prix - but very carefully! I have visited the Porsche Museum recently where the car with which I won is on display - and when I looked at the construction I could not believe that we drove at 390 km/h on the straights at Le Mans. The car looked so fragile. So I was really lucky having survived this era.

Of course, Jochen tragically didn’t survive. How did his death affect you? Did it make you question your career and whether to continue?

HM: When I got the message that he got killed I couldn’t believe it because at that stage he was not driving as riskily as he was at the beginning of his career. Yes, the Lotus was a fast but fragile car, but Jochen wanted to win races and championships. At his funeral I got an offer for a seat. That showed me what motor racing is like - life goes on. The following year I myself had an accident at Daytona Beach - in the banked corner. I was in the 300 km/h range when I had a puncture. In the time between understanding that I had no chance [to save it] until the time I hit the wall it crossed my mind: ‘Christ, I should have stopped racing!’ It was unbelievable that in two or three seconds your whole life passes by. You remember even some girls. But the most intense thought was: ‘You are finished’. But in the moment that I hit the wall I pushed the fire extinguisher, as I knew that these cars easily caught on fire. Then I opened the doors so as not to suffocate - everything came automatically. The survival instinct immediately set in.

You made your F1 debut for Jo Bonnier Racing, driving a McLaren at the 1971 German Grand Prix – what was that like? Do you remember the experience?

HM: I can’t remember much. It was on Nurburgring Nordschleife and that is not the nicest place to jump in an F1 car. And I can’t really remember why I didn’t race - I just did practice. I think I was in negotiations with Surtees and with BRM, and Surtees thought that I had signed the contract, but I hadn’t - so there were some legal arguments. But I remember the Austrian race two weeks later when I realised how difficult these cars were to drive. It took me quite a while to push the car to the limit.

As you say, you got the drive with BRM for your home Grand Prix and you obviously made a good impression because Louis Stanley invited you to complete the season…

HM: Yes, BRM was a big name at that time. Big history. Louis Stanley was probably the first who got a real sponsorship contract: he brought Marlboro into F1. The glamour was there but BRM was sometimes running four or five cars at a race, so the cars were not prepared to the highest standard. But it was a good experience. And after a while I moved up in the hierarchy of the team - and when I finally sat in the right car I had the accident. I was so eager to get into the new chassis – I was sitting 15cm higher than in my normal car and could hardly move my legs – but I wanted that chassis. With my old chassis the accident would have never happened, as the stone wouldn’t have hit me.

"I was so eager to get into the new chassis - I was sitting 15cm higher than in my normal car. With my old chassis the accident would have never happened, as the stone wouldn’t have hit me…" - Marko on the freak accident that ended his racing career

Does it still go through your head what would have happened if you hadn’t pressed for that chassis?

HM: Just get this: an injury in the eye is very painful. They had to sew the eye, so every blink was a horror. I couldn’t sleep for many nights also because I still was full of the idea that motor racing is the only reason to live. And then in one of those sleepless nights I had to confess to myself: it’s over, I would have to do something else with my life. That is when you fall into a deep black hole. But then I realised that there is life after racing, and something switched in my head from one moment to the other - I didn’t jump in a race car again for the next 30 years. I knew back then that I would never again be able to compete on a competitive level and I didn’t want to end up as a ‘gentleman driver’. Now I have to say that I am really happy and lucky that I survived that period with only the loss of an eye.

Of course, today, with all the medicine on hand at tracks and improvements in surgical procedures, your injuries might have been curable…

HM: First of all: after my accident they introduced new visors - more or less bulletproof ones - so that injury would not have happened. But there are so many improvements - probably too many in my view as there always has to be a certain level of risk, otherwise you could look for a career as cabbie.

Did you know straight away you were in big trouble?

MH: No. Yes, it was absolutely painful, but I drove a 12-cylinder and Clermont-Ferrand was a long race, so I immediately had the fuel load in my head. In that moment I was in fifth or sixth and it was an uphill part of the track, so I knew that this could turn into an inferno – for me and those behind me. What happened next I have no memory of, but I was told that I lifted my arm and managed to park the car on the side of the track - then I fell unconscious.

"Niki got the contract with Ferrari that I originally had, but I am not envious. We still have a good relationship. And do I ever think: ‘Wow, actually that could have been me’? No, I am not a dreamer." - Marko (left) on countryman Niki Lauda

What do you remember of your F1 team mates?

MH: In my first year it was Jo Siffert, who died at Brands Hatch in 1971 when his upright broke - and only some races later I had the same failure in Brazil. That shows how safety was controlled at that time. Then it was Howden Ganley, a Swedish driver whose name I cannot remember [Reine Wisell], and sometimes an English guy – Peter Gethin – who was a lot of fun. From the four of us only Howden and I are still alive.

Do you ever think about what you might have achieved in F1 were it not for your injury? Some believed you were as good - if not better - than Niki Lauda. How did it feel watching him go on to great success?

HM: I don’t have a problem with that. Niki got my seat at BRM. Niki got the contract with Ferrari that I originally had, but I am not envious. We still have a good relationship. And do I ever think: ‘Wow, actually that could have been me’? No, I am not a dreamer. Actually it was me who went with Niki to Mr Enzo Ferrari when he first met him. It was a very impressive visit: you came into this dark room, with him sitting there with even darker glasses on. It was very mysterious. (Laughs)

Q That sounds like Niki step-by-step took over what you had already set in place for yourself?

HM: Exactly.

Have all of the young drivers you’ve worked with been aware of the fact that you were a top driver in the past?

HM: I don’t know. I don’t ask them.

"Do the drivers I've worked with know I was a top driver myself? I don’t know. I don’t ask them. " - Helmut Marko

Do you ever refer to your own racing career when talking to young drivers?

HM: The times are so different now that stories of the cars I drove in the old days would be a waste of time. What I talk with them about is that you have to be competitive, be completely focused and so on. That is what I am trying to pass on to them. But wait: I did once get a call from Daniel (Ricciardo). He was driving my Alfa Romeo in a Targa Florio show run, and he complained that the clutch was so heavy, and that the brakes were so difficult. Probably he got a glimpse of how hard it was in the old days. I told him: ‘You get paid one hundred times more than we did – or let’s say ten times – you have much less work, much safer cars – so enjoy and be grateful!’

So do you not ever offer practical driving advice? How much of your own experience as a driver do you call upon, or is it, as you say, just so different these days?

HM: I probably would say: try to plan your race weekend differently – more efficiently. Don’t try to be the fastest on Friday – leave something for qualifying. Or like in Monaco, I probably would say: try a different line. Simple experience that you get when you have been in motor racing for 50 years!

Q: That leaves one more question: what’s been your best moment of those 50 years?

HM: I would probably have to pick three: winning Le Mans – that was a big moment. Winning the first championship with Sebastian Vettel for Red Bull. And, believe it or not, last year in Barcelona when Max (Verstappen) won the race. I was called mad for putting him in the car, even within the team – and then he goes out and wins!

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News ‘It was the only option’ – Verstappen explains alternate tyre strategy in Monaco after going from P1 to P4 on final lap

News Horner explains why Red Bull ‘rolled the dice’ with Verstappen strategy in Monaco as he reflects on ‘jeopardy’ of race

News ‘This is just the start’ – Stella backs Norris to hit top form after ‘cold blood’ Monaco victory

News 'We put everything together when it mattered' – Ocon thrilled with return to the points in Monaco