Technical

Re-writing the F1 rule book - Part 1: from wing cars to flat bottoms

Share

The 2017 season sees arguably the biggest technical shake-up in F1 racing for 20 years, with the rule makers adopting a previously unseen approach of changing the regulations to raise speeds rather than keep them in check. In the countdown to the new campaign, we look back over the other occasions in the modern era when F1 designers have been forced into a fundamental re-think by a dramatic rules shift, starting with the move from ground-effect aerodynamics to flat-bottomed cars in 1983…

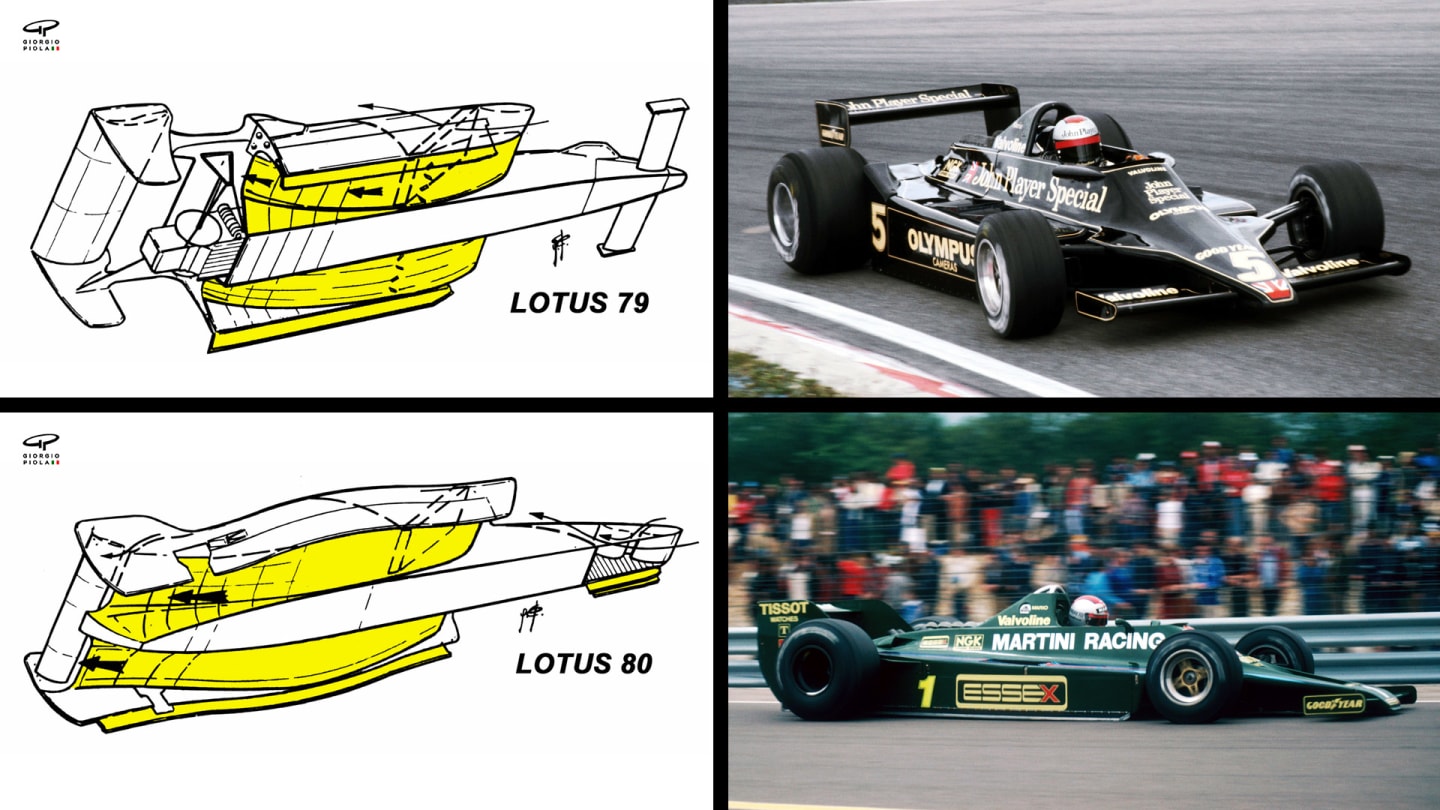

A product of Colin Chapman’s perennially innovative Lotus team, ground effect technology came to dominate aerodynamic development in F1 in the late Seventies and early Eighties, leading to huge gains in cornering grip and performance. The key was exploiting an aerodynamic principle known as the Venturi effect, whereby the underside of the car could be designed so as to make the entire chassis act like one giant wing which sucked the car to the ground. The Lotus 78 of 1977 gave a first indication of what was possible by shaping the underside of sidepods and sealing in the low pressure with side skirts, but it was the Lotus 79 (pictured above), introduced the following year, that took full advantage of the principles with its more refined Venturi tunnels and diffuser.

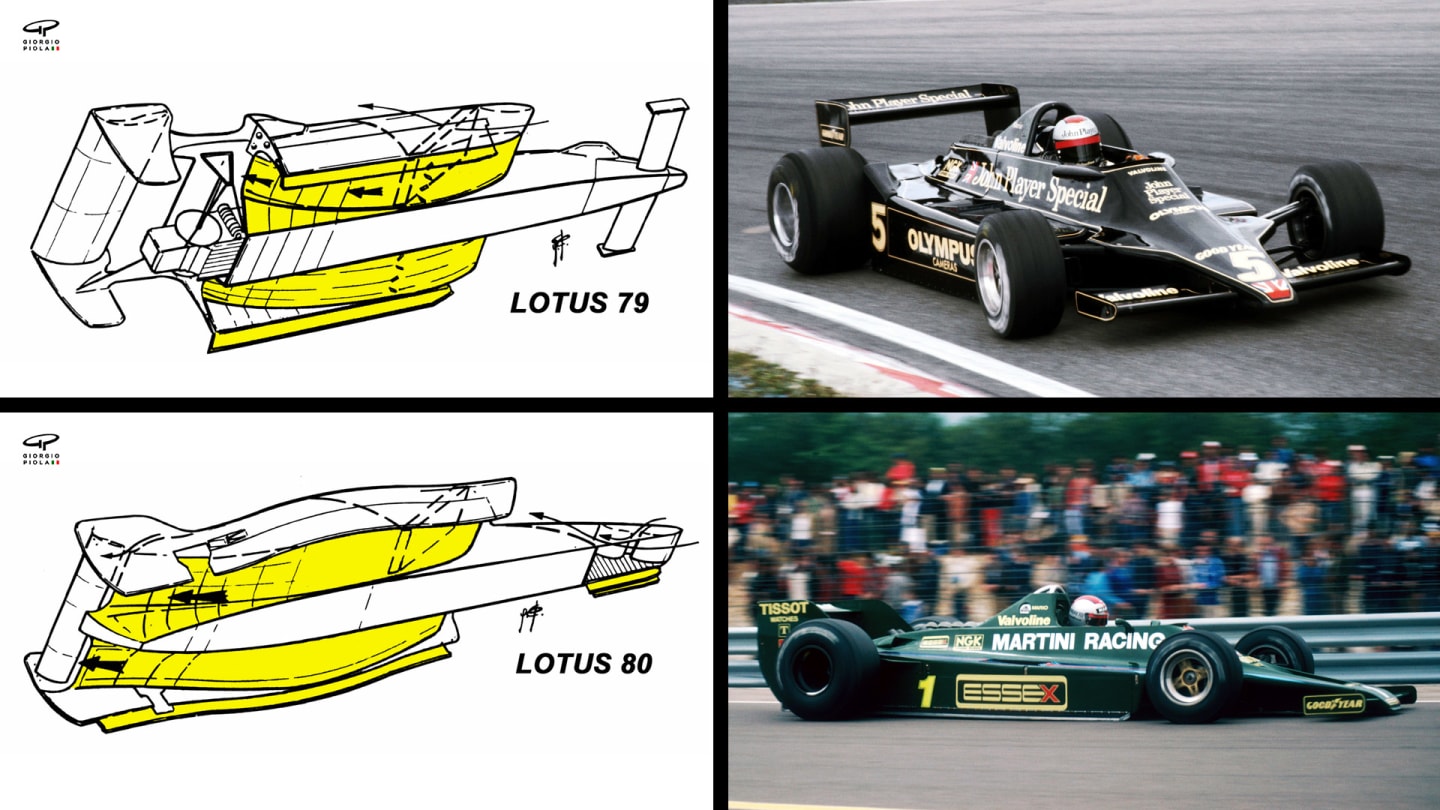

As Lotus dominated the 1978 championship, winning half of the races, other teams inevitably decided to follow their design lead, and a swathe of ground effect cars appeared - including the infamous Brabham BT46 ‘fan car’ (pictured above) which featured not only skirts but a large fan to reduce pressure under the car.

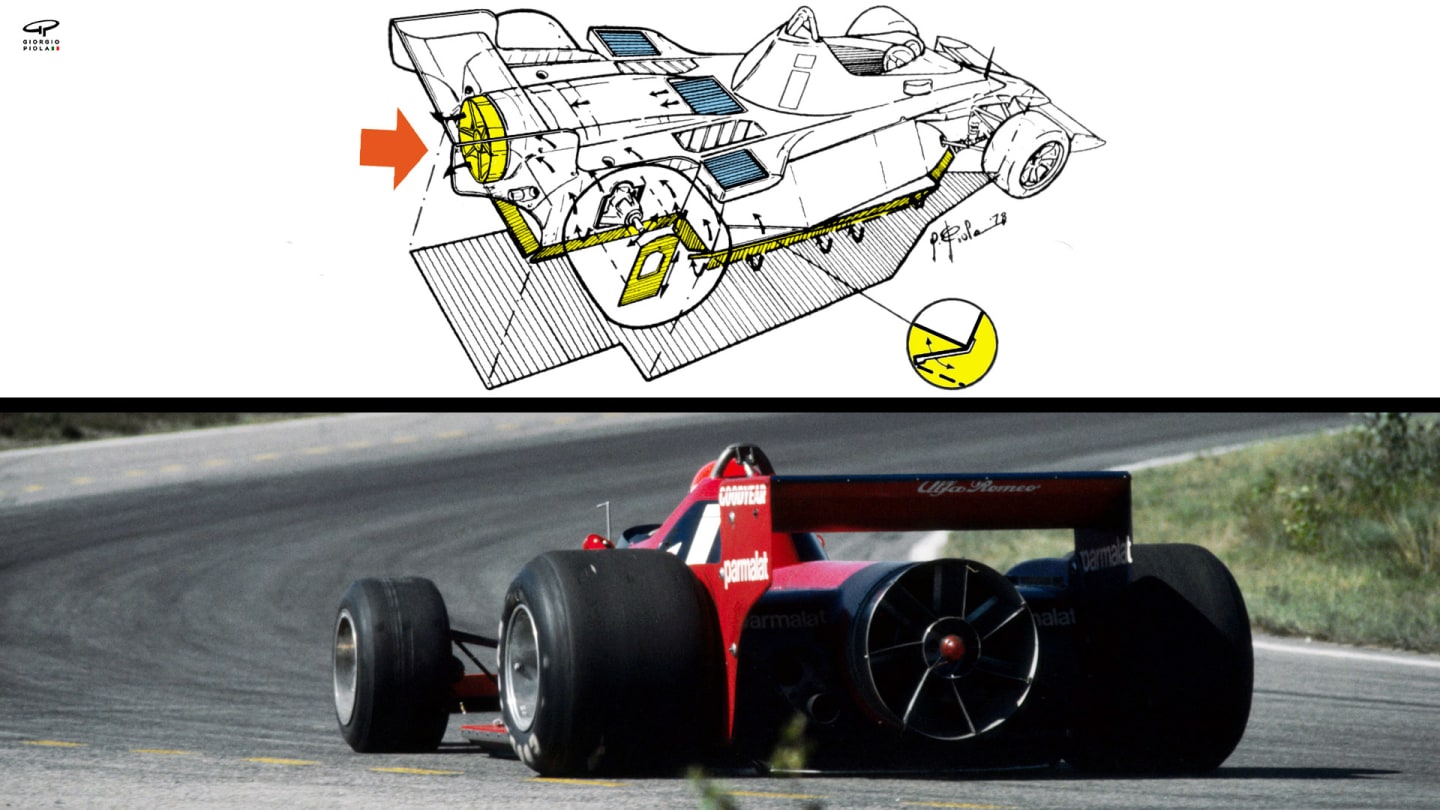

In the face of protests, the fan car concept was soon withdrawn, but more extreme ground effect solutions followed the next season, including the Lotus 80 (top picture) and the Arrows A2 (pictured below), both of which practically dispensed with traditional wings altogether in favour of complex and ambitious skirt and tunnel layouts. But while the ‘more is better’ ground effect theory seemed good on paper - and indeed in the windtunnel - in reality these cars (and others) proved highly unpredictable, never able to guarantee a constant level of downforce. The low pressure area in particular proved hard to control, often moving around (leading to an alarming new phenomenon known as ‘porpoising’ where the car would dip and heave) or in some cases disappearing altogether when a skirt became dislodged or broken.

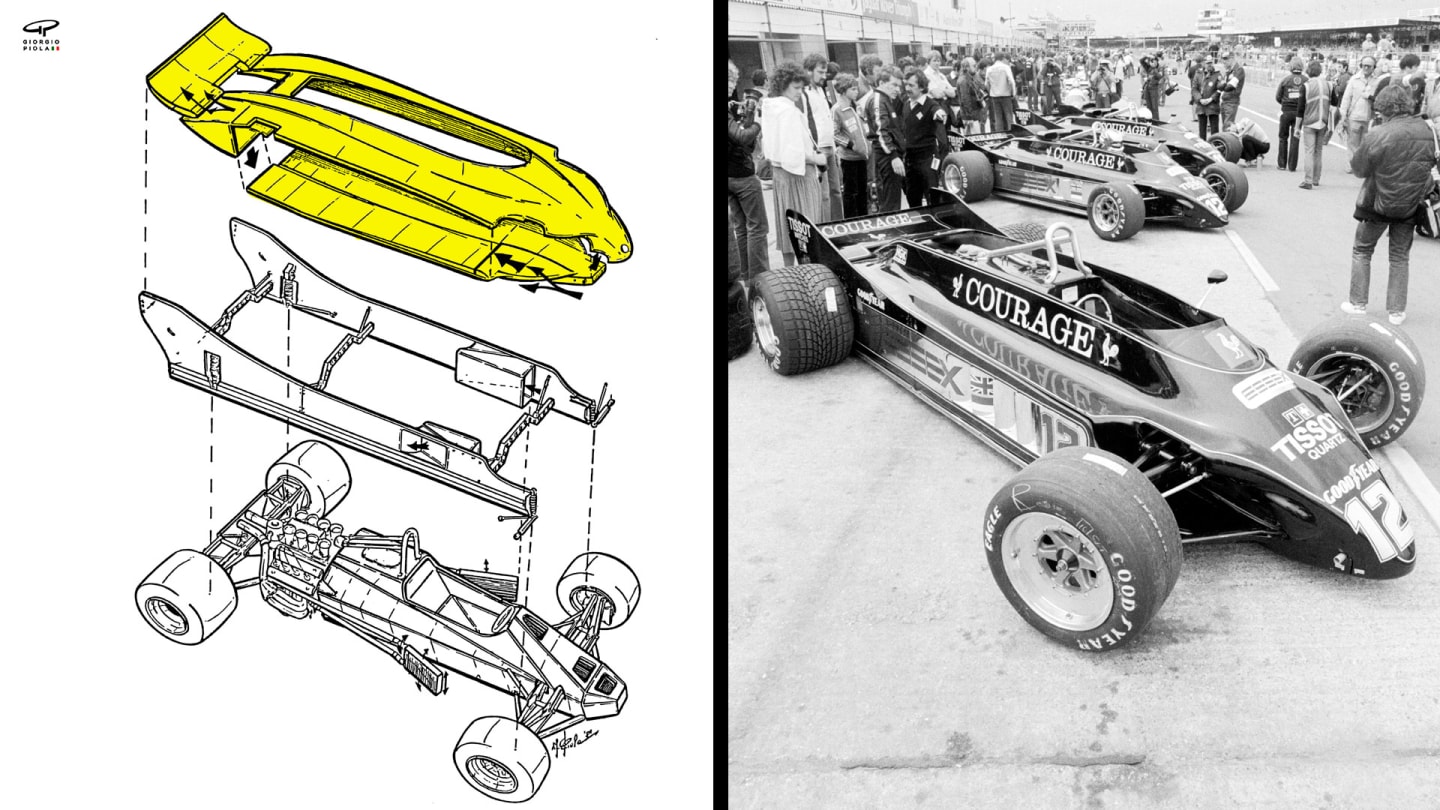

Alert to the dangers, including massively increased cornering speeds and G-forces, F1’s regulators moved to limit the benefits of ground effects in 1981 by banning skirts and introducing a mandatory ground clearance of 6cm. But the teams weren’t so eager to dispense with the enormous gains they’d found, and several ingenious solutions were developed to get around the new rules. Amongst them was Lotus’s innovative 88 model (pictured below) which featured effectively two chassis, one inside the other. The inner chassis was essentially a conventional car independently sprung from the outer bodywork skin, which acted as one large wing that lowered to the ground at speed but returned to a legal height in the pit lane.

The 88 was banned before it could be raced, but Brabham’s own rule-circumventing solution, the BT49, which featured skirts that automatically lowered on track, was to Lotus’s chagrin cleared to race, dominated immediately, and copied (in crude fashion) by rival teams.

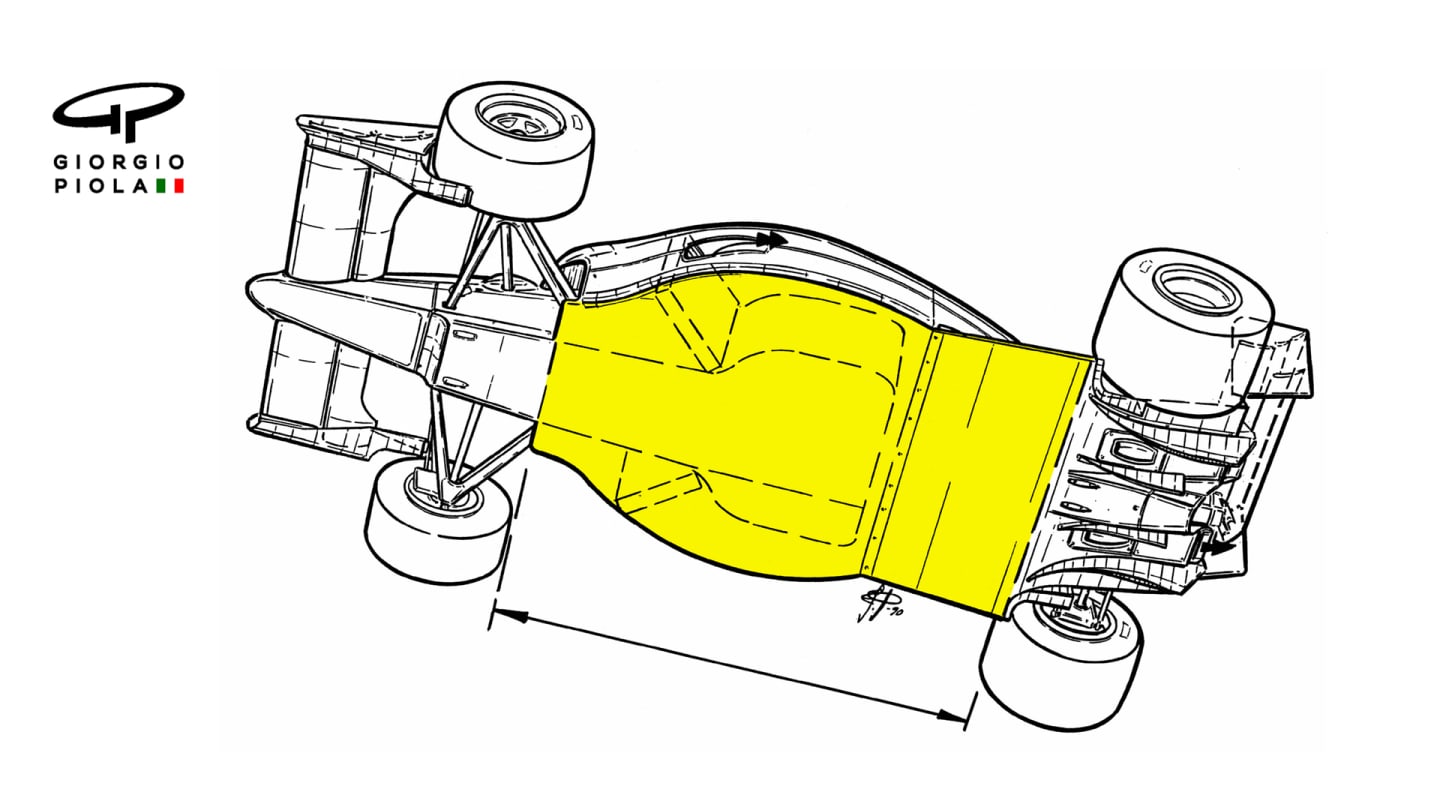

In fact it wasn’t until 1983, after a campaign blighted by a number of serious accidents, that ground effect technology as designers knew it was stopped in its tracks by a new requirement that mandated F1 cars have flat bottoms between the inside tangent of the tyres (pictured above) and no skirts (which had gained a temporary reprieve in 1982).

The effect of this rules revolution was massive, with a big reduction in cornering speeds. Nelson Piquet was the first champion of this new era, his Brabham BT52 (bottom picture, below) a vast departure in all but livery from its predecessor, the BT50 (top picture, below), but no less innovative in its own way.

Illustrations © Giorgio Piola, Images © Sutton Images / LAT Photographic

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News Silverstone confirms UK icons to headline 2025 British Grand Prix Festival

News ‘I want to make my own story’ – Antonelli says it’s ‘not right’ to view him as Hamilton’s ‘replacement’

VideoF1 Unlocked WATCH: Sainz, Albon and Vowles unveil Williams’ new car livery for 2025 at F1 75 Live

Feature IN PHOTOS: Every 2025 F1 car livery after their spectacular F1 75 Live unveilings