The 2017 season sees arguably the biggest technical shake-up in F1 racing for 20 years, with the rule makers adopting a previously unseen approach of changing the regulations to raise speeds rather than keep them in check. To mark this dramatic shift, we’re looking back over the other occasions in the modern era when F1 designers were forced into a fundamental re-think, with our next focus on the late nineties when cars got narrower and tyres got groovier...

)

In Part 2 of our look back at the technical rule changes that have shaped the modern era, we chronicalled the raft of measures that followed the tragic deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger in 1994. This included, in 1995, the introduction of the stepped flat bottom, a measure which at the time slashed overall downforce levels by as much as 30 percent. But such is the rate of progress in F1 racing that by the end of 1996 speeds had rapidly risen once more, and with the introduction of a second tyre supplier for 1997 - Bridgestone - they would only accelerate further.

Keen to prevent cornering speeds from spiraling out of control again, FIA President Max Mosley tasked the F1 Technical Working Group with coming up with proposals to reduce performance, an investigation that would run concurrently with a similar study into increasing overtaking. The resulting changes to the regulations were sweeping.

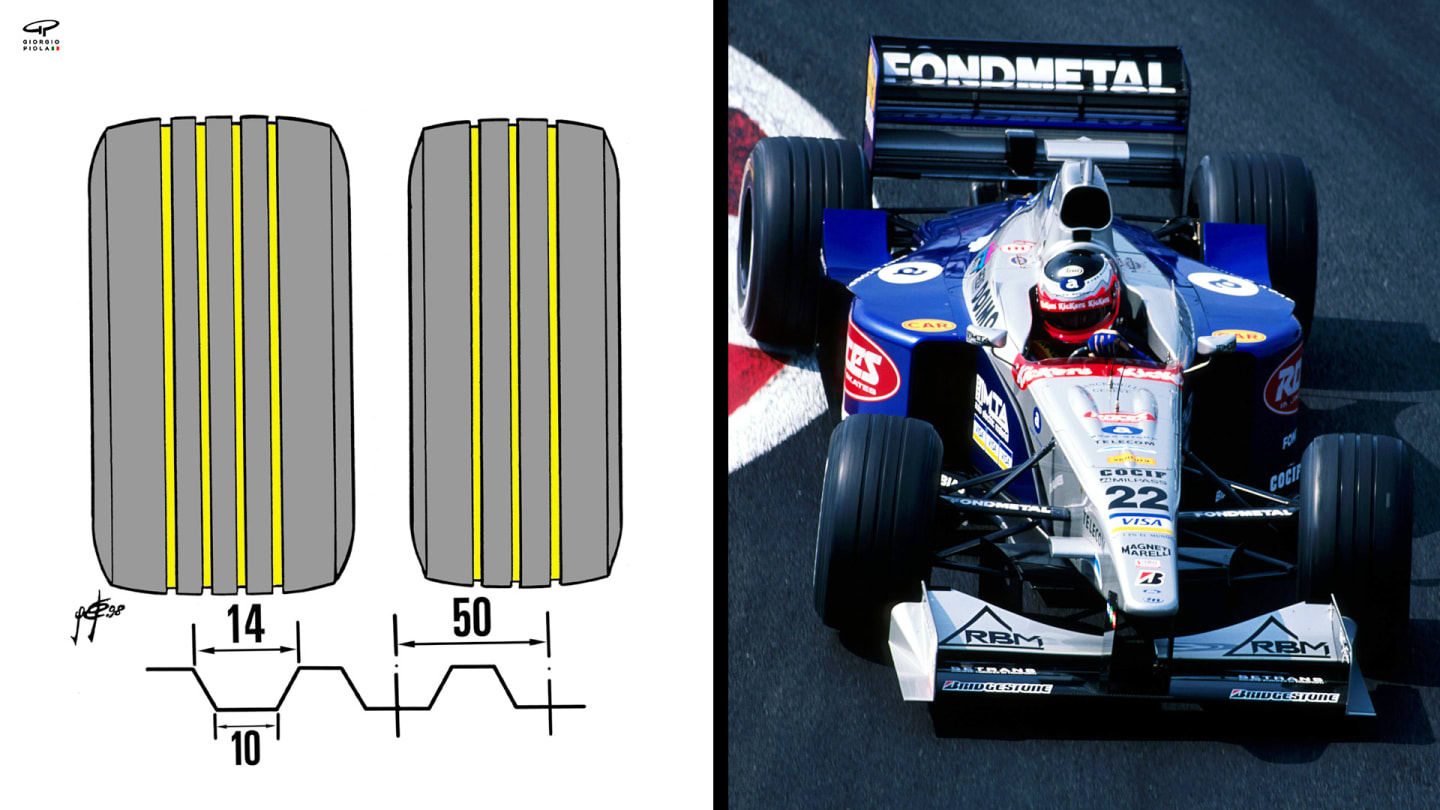

The first - and outwardly most significant - rule change related to the tyres, with F1 racing’s familiar slick rubber disappearing in favour of a new grooved model. This was a simple, if rather inelegant and unpopular way of reducing a tyre's contact patch (and therefore potential to grip, particularly in corners) without reducing the overall size of the tyre. The new structure - which offered around 12 percent less rubber on the ground - also meant that compounds had to be fundamentally harder, plus the rulemakers also had the option of adding further grooves to control speeds, which they did in 1999, introducing a fourth groove to the front tyre so that it matched the rear.

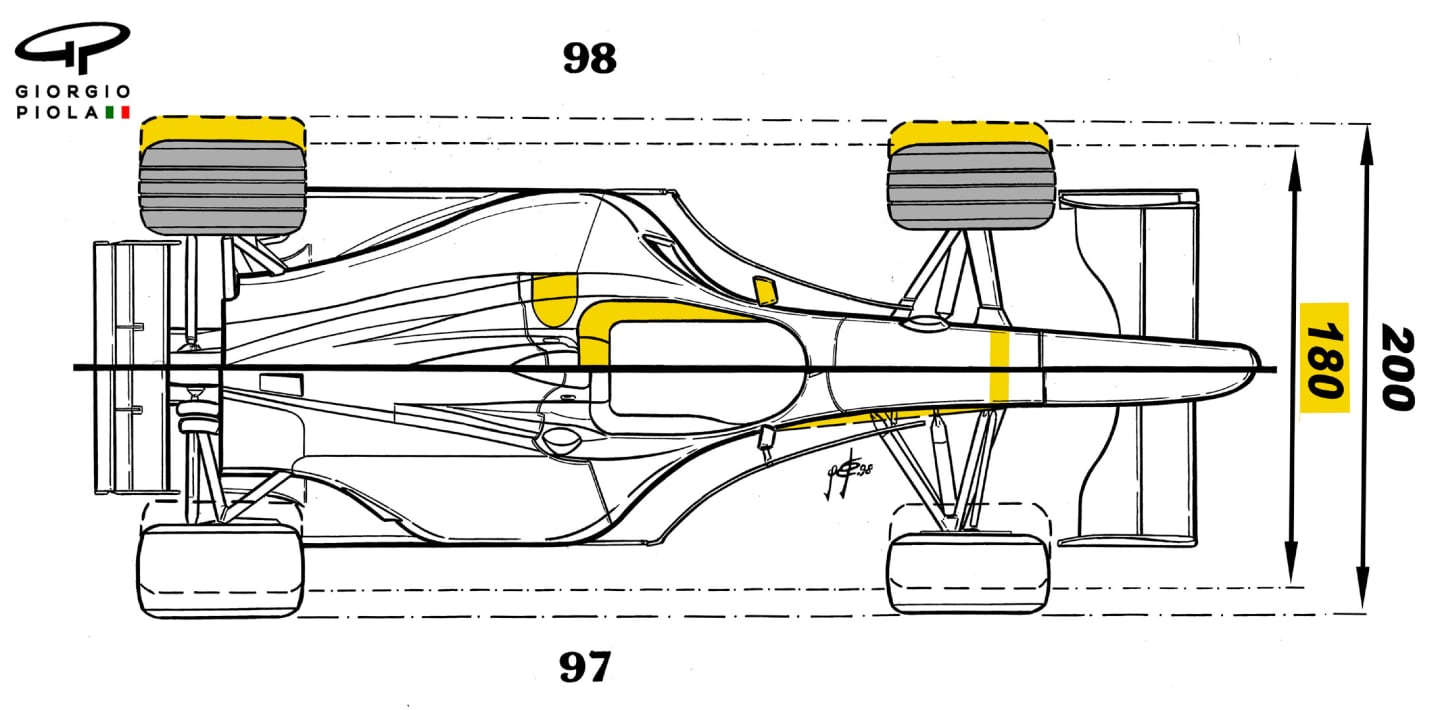

The second major rule change was to the overall width (or track) of the cars, which was slashed by 12 percent from 200cm to 180cm (see above and below). This move, which meant that the cars were now 35cm narrower than they had been in 1992, had several huge implications on performance, though the rulemakers also hoped it might open up overtaking opportunities on the basis that there would be slightly more space available on track.

Firstly, moving the tyres inboard (shown clearly in the picture above) had a profound aerodynamic effect, impacting airflow all the way down the car from the front wing to the rear, above chassis and below. Some estimates put the downforce loss at as much as 20 percent - though the teams would rapidly start to claw this back.

Secondly, by narrowing the track when it wasn’t possible - for packaging and aerodynamic reasons - to reduce wheelbase by the same ratio, the cars felt fundamentally less stable because though the teams did their best to combat them, there were unavoidable changes to weight distribution and centre of gravity.

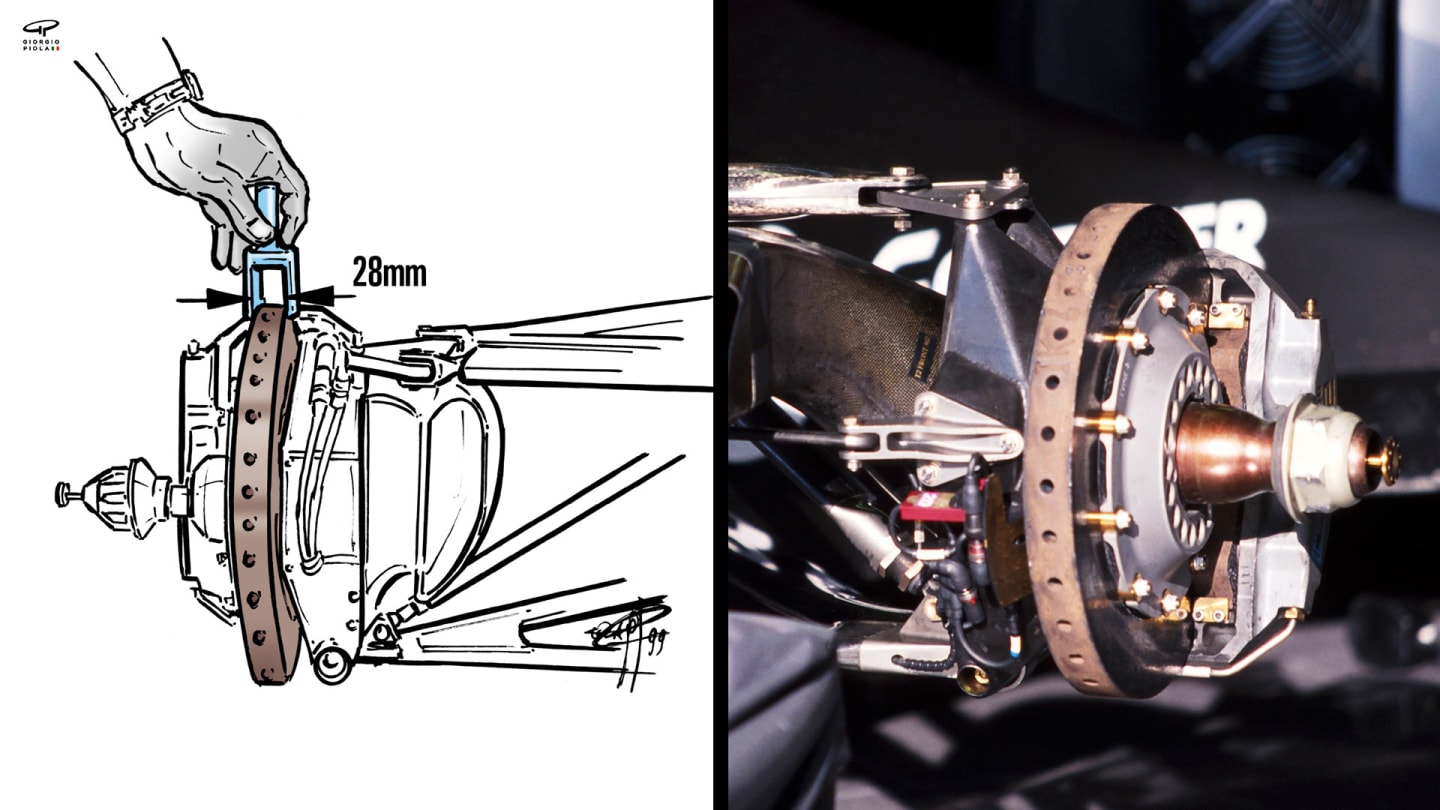

The third major rule change was to brakes (pictured below), with the FIA making several moves aimed at limiting braking performance, improving the possibility of overtaking and reducing costs. The first decision was to ban teams from using exotic materials (like Beryllium, a material available to some but not all) and return to plain aluminium calipers with a designated maximum stiffness. The teams would also be limited on each wheel to no more than one caliper (with a maximum six pistons), no more than one brake disc and no more than two brake pads. Disc thickness was also cut from 34mm to 28mm - a size that is only being changed this season, when it goes back up to 32mm.

On the safety side, the 1998 season saw F1 racing take yet another step forward. The minimum internal dimensions of the front section of the survival cell were increased as was the strength of the chassis walls, with the side-impact test speed increased such that F1 cars had to withstand nearly 100 percent more energy. With the side headrests extended to the steering wheel (highlighted in red below), there was better cockpit protection for the driver, while wider wing mirrors improved visibility. Finally, the single fuel bladder became mandatory, with teams also required to cover the refuelling connector.

The extent of the changes meant that F1 cars in 1998 were almost clean-sheet-of-paper designs, but did the regulations achieve what they set out to do? Yes and no. At first the changes did have the effect of slowing the cars significantly, but by the first race of the season in Australia (pictured below), Mika Hakkinen’s pole lap was less than a second slower than the previous year’s had been on slicks. And such was the pace of development and the intensity of the tyre war between Goodyear and Bridgestone that speeds crept up ever further as the season wore on.

Progress, in F1 racing, is hard to contain.