Technical

Re-writing the F1 rulebook - Part 4: ‘cleaner’ cars, KERS and the return of slicks

Share

The 2017 season sees arguably the biggest technical shake-up in F1 racing for 20 years, with the rule makers adopting a previously unseen approach of changing the regulations to raise speeds rather than keep them in check. To mark this dramatic rules shift, we’re looking back over the other occasions in the modern era when F1 designers were forced into a fundamental re-think, with our next focus on 2009’s major rules overhaul…

As the 2000s neared their conclusion, Formula One cars had morphed into the most aerodynamically (and visually) complex machines in history, with all manner of appendages, turning vanes and winglets sprouting from their bodywork. From the FIA’s point of view, there were two major problems with this: firstly, these kind of developments hadn’t come cheap, with teams running wind tunnel and CFD programs flat out in pursuit of an advantage.

Secondly, and more importantly from a racing point of view, these highly tuned aerodynamic beasts were extremely sensitive, with drivers losing considerable downforce when running in another car’s wake. Overtaking wasn’t impossible, but it was becoming increasingly difficult, and increasingly rare. Something, the FIA decided, must be done to combat these issues, as well as to improve F1’s green credentials and the category’s road relevancy. The raft of revolutionary technical regulations that arrived in 2009 were the solution, with the resulting cars looking extremely different.

The first area that saw radical overhaul was aerodynamics, with the regulations being shaped around investigative work carried out by the Overtaking Working Group (OWG). This crack team of engineers - which could count Paddy Lowe, Pat Symonds and Rory Byrne amongst its members - found through extensive wind tunnel testing that a taller and narrower rear wing (see below) created a better wake for the following car, and thus the regulations were tweaked in that direction.

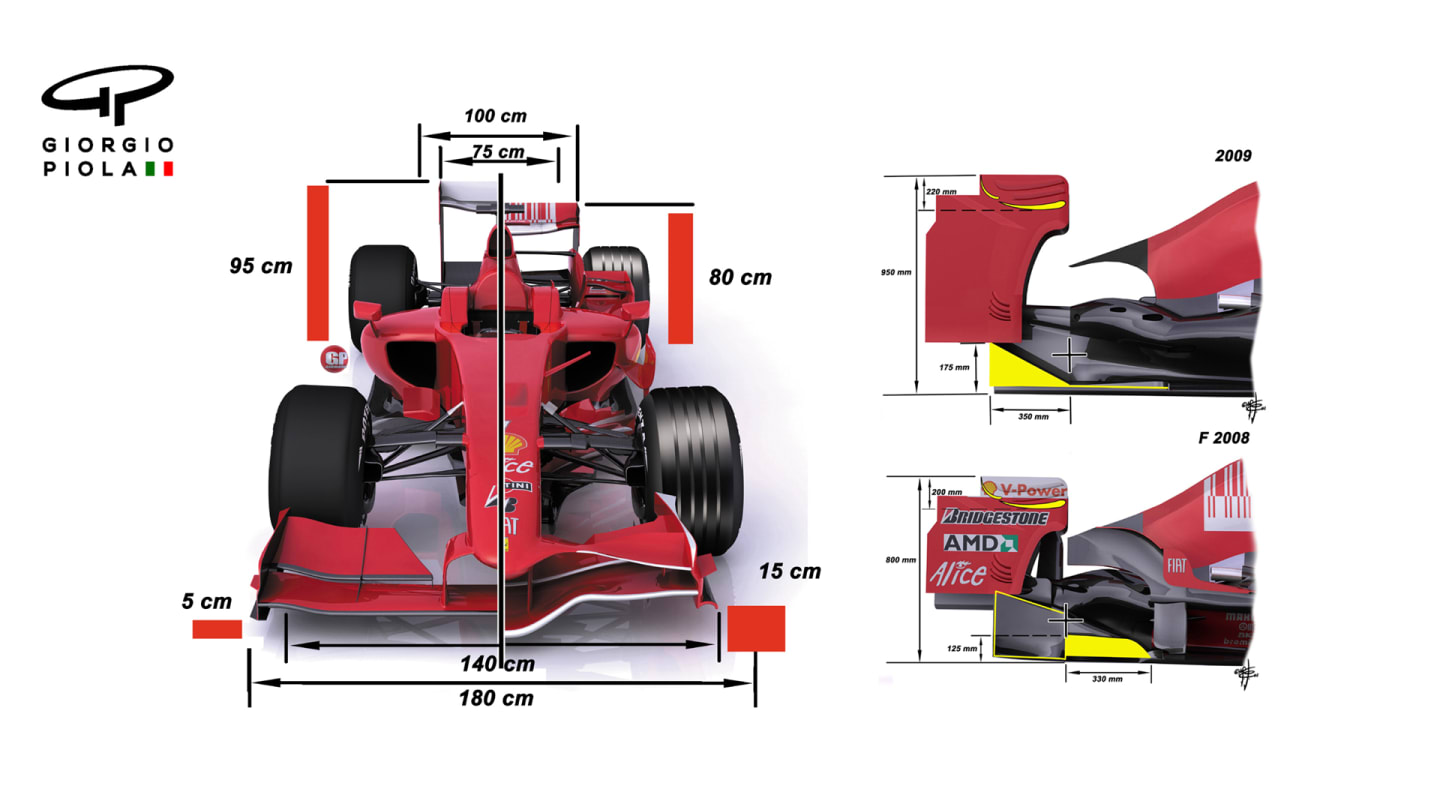

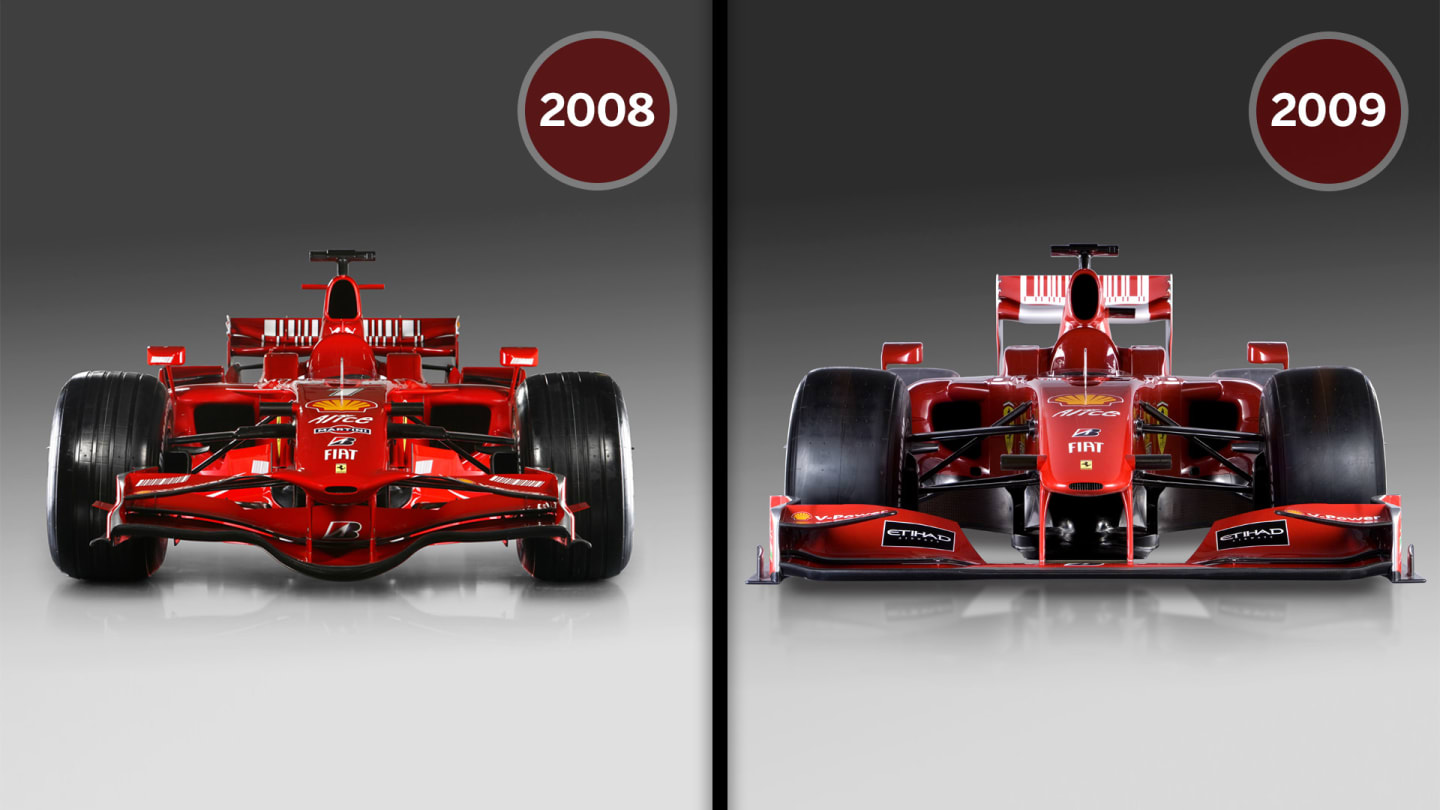

Similarly, it was concluded that a lower, wider front wing (pictured below) was less susceptible to a loss of downforce when running behind another car, leading to front wings extending well out in front of the front tyres in 2009.

These new wings, which were also made significantly simpler thanks to an FIA-mandated neutral section in the middle (see below), also featured active aerodynamics, with the driver able to make two front-wing-flap angle changes of up to six degrees per lap in a further move to help boost overtaking. In reality, this concession proved relatively insignificant, with some pointing to the fact that the wider wings might actually make overtaking more hazardous.

In a further attempt to clean up airflow and contribute to a targeted reduction in downforce of 50%, the rest of the car was smoothed out, with the regulations putting paid to the various chimneys and other unsightly aerodynamic devices that had become de rigueur (see below).

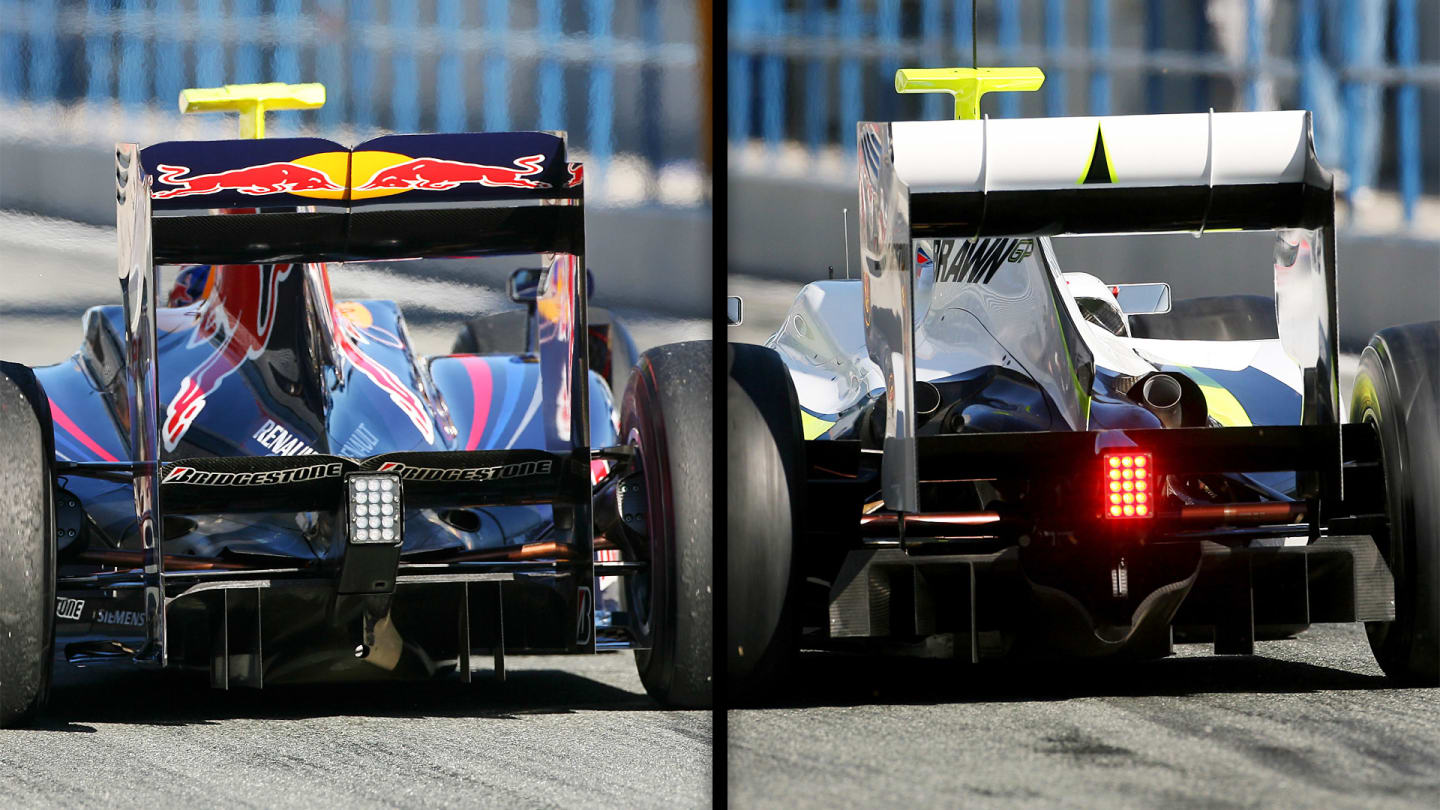

A much-revised diffuser was supposed to be the final piece of the aero-slashing package, but it wouldn’t be long before Williams, Brawn and Toyota found a controversial loophole in the wording of the regulations and created the so-called ‘double diffuser’. This more-expansive device helped claw back a significant chunk of downforce, and left rival teams scrabbling to play catch-up, once their protests against the layout (which they claimed went against the spirit if not the letter of the regulations) were waved off. The differences between Brawn's double diffuser (right) and Red Bull's 'as the regulations intended' design (left) can be seen below.

The second significant area of overhaul was to the tyres, with slicks returning after an 11-year absence to replace the long admonished grooved rubber. This switch also followed the OWG’s thinking, the theory being that if you reduced downforce and at the same time improved mechanical grip by putting more rubber on the road (in this case by between 6-8%), racing would improve. The move back to slicks was a relatively straightforward task for then-tyre supplier Bridgestone, but it was a far bigger consideration for the teams, with the loss of grooves affecting the narrower front tyres more than the wider rears, resulting in a change of grip ratio and subsequently a push towards a more forward weight distribution and aero balance than before.

)

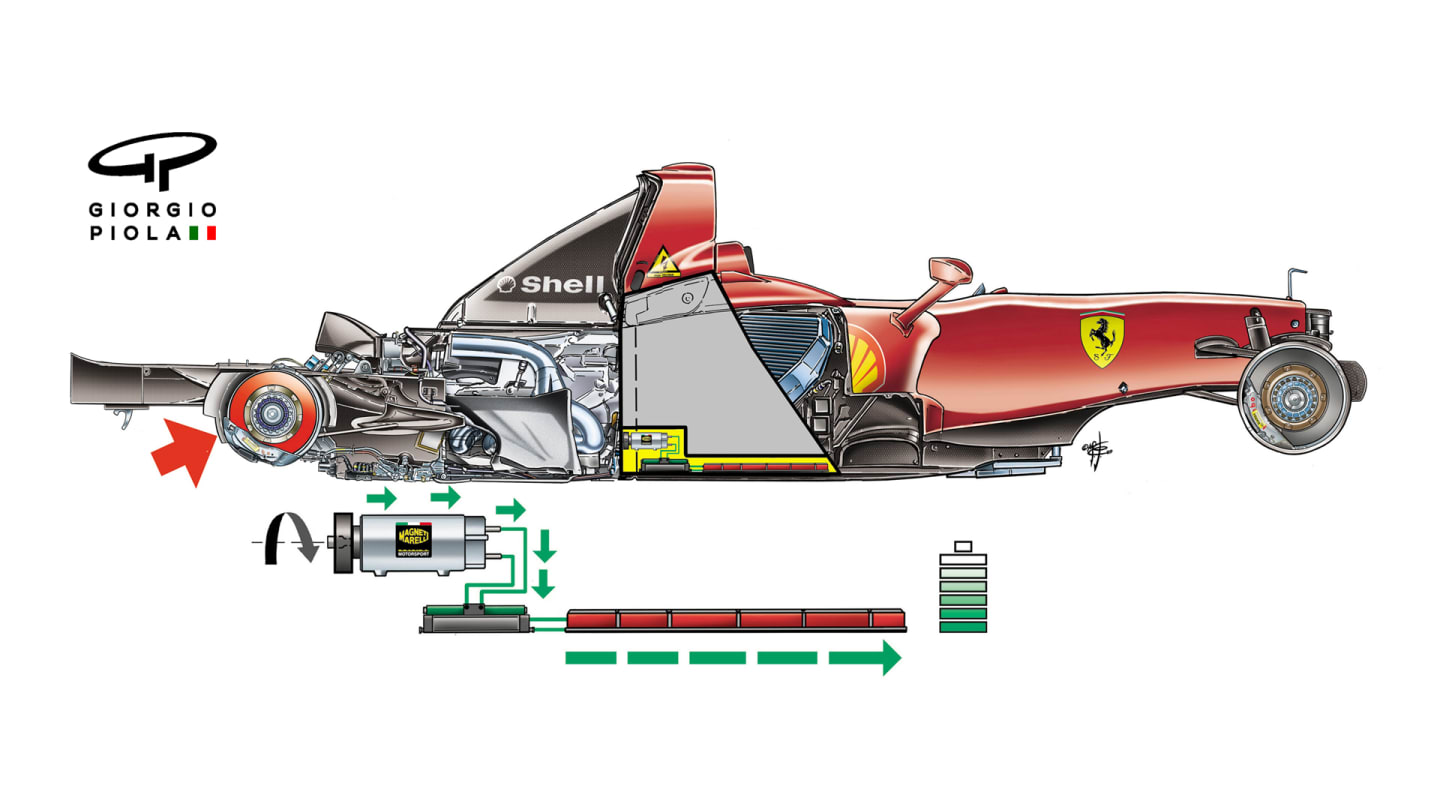

There were also changes on the powertrain side of things, with a new rule restricting drivers to eight engines across the 18-round season, all of them with a new 18,000rpm rev limit. But the bigger news on this front was the introduction of Kinetic Energy Recovery Systems (KERS), which would see F1 cars gain a new road-relevant, energy-efficient power source. The rules allowed the new systems, which still form part of today’s Energy Recovery Systems, to return a power boost of up to 80bhp for up to 6.6 seconds per lap, the energy having been harnessed under braking via a motor generator unit and then stored in either batteries (most teams, as shown in the diagram below) or an electric flywheel (Williams).

It was hoped KERS would further aid overtaking, but in practice the temporary power boosts were more commonly used in defence. And that wasn’t the only issue in year one either. For a start there were the potential safety implications of running with a ‘charged car’, but more importantly the systems were extremely heavy and complex to package. In fact, with the technology still in its infancy (and in a lot of cases very unreliable), many teams opted not to race with KERS at the first race of the new era in Australia (pictured below), the performance trade-off marginal in the face of potentially superior weight distribution and cooling.

Two of the teams ‘without’ in Melbourne were Brawn and Toyota - and they swept the podium. But at round 10 in Hungary Lewis Hamilton took his KERS-equipped McLaren (pictured below) to victory. And by then the fans had just about got used to the look of the new cars too…

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Video WATCH: Lawson out, Tsunoda in – Laura Winter and Lawrence Barretto discuss Red Bull’s driver call

Video LIVESTREAM: Watch the action from Qualifying for Round 12 of the 2025 F1 Sim Racing World Championship

News ‘It’s tough’ – Lawson shares first message after Red Bull seat swap with emotional social media post

FeatureF1 Unlocked Crypto.com Overtake of the Month – Vote for Your Favourite Move Now!