30 May - 01 June

Feature

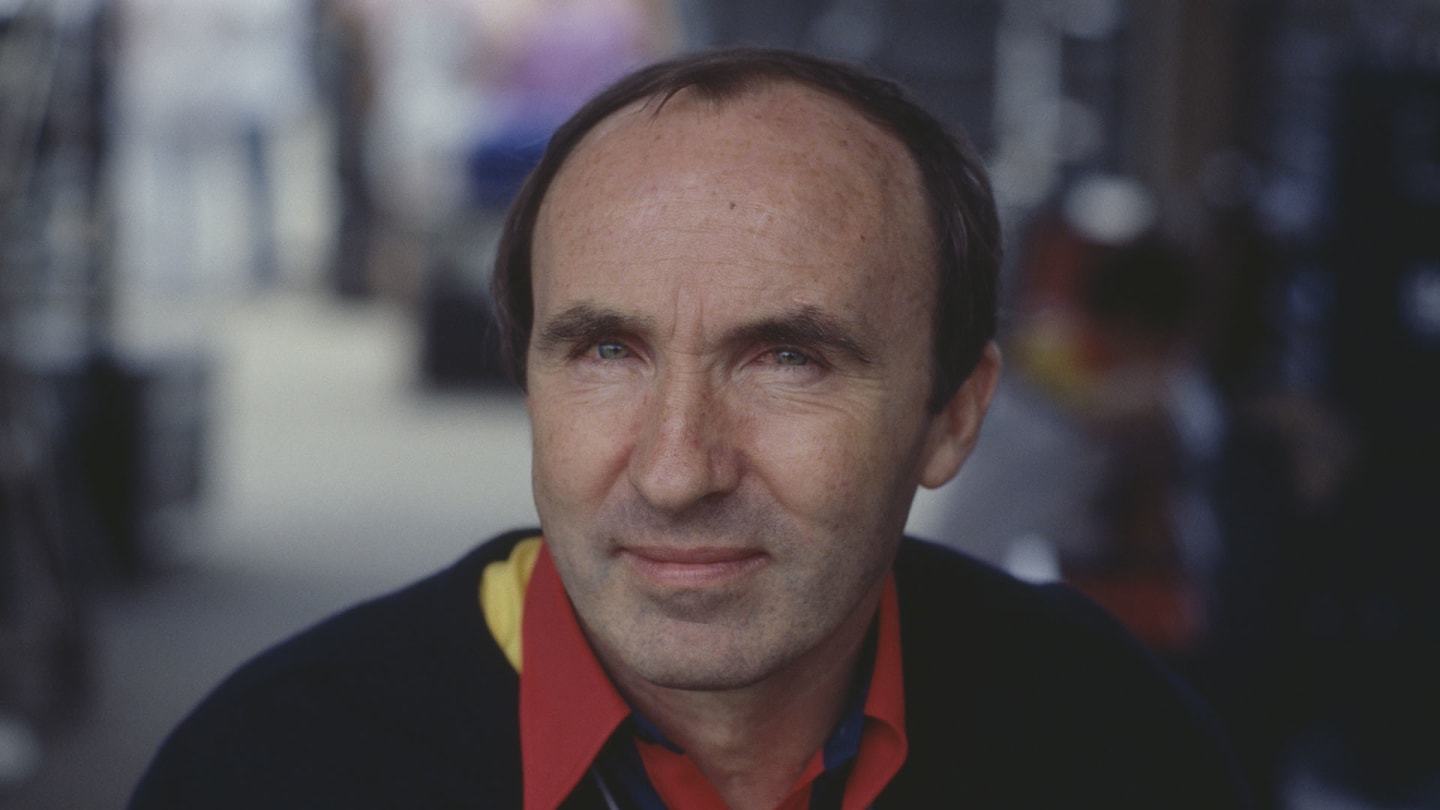

Sir Frank Williams, 1942-2021 – F1’s champion-maker remembered

Share

For a split second it seemed that there was barely a sound. Then, above the scrape of chairs and the rustle of clothing as 300 people rose as one, spontaneous applause erupted unbidden.

It was July 11 1986, in the press room for the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch. Not a particularly salubrious place, but in that moment it hosted something very special. Just four months after the car crash on the way back from testing at Paul Ricard which had left Frank paralysed, there he was, being wheeled into the room to a heartfelt ovation. There were lumps in throats and damp eyes as everyone lauded his courageous return.

READ MORE: Legendary F1 team boss Sir Frank Williams dies, aged 79

He would cope brilliantly with the way in which that life-changing crash transformed him from a super-athlete who regularly beat the drivers in running races at Grands Prix into a wheelchair-bound man who became one of the world’s oldest quadriplegics. And he would do so with indomitable strength, dignity and a quite amazing lack of self-pity. “I deserved that, the way I used to drive,” he once said. And referring to passenger Peter Windsor, the writer and Williams team manager, he added: “I was glad it happened to me, and not to Peter. I would never have forgiven myself had he been the one to suffer.”

Francis Owen Garbett Williams, born in South Shields and raised mainly by a maternal aunt and uncle in Jarrow, grafted his way up the slippery slopes of the sport. Whenever the word went round the paddocks in F3 in 1982 and ’83 that Frank was present, you also most stood to attention like schoolboys preparing to be inspected by the headmaster.

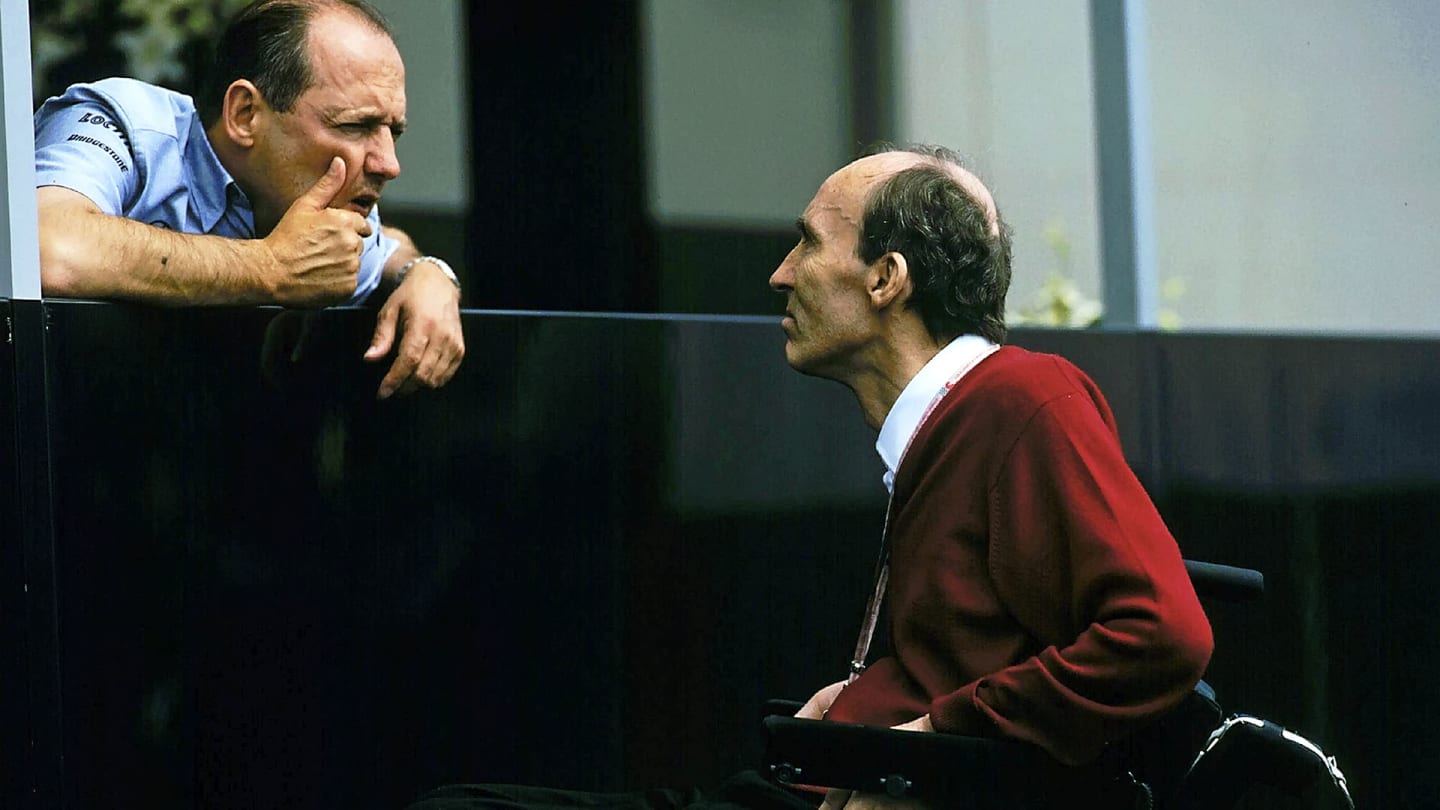

Peter Windsor was alongside Frank Williams during the fateful 1986 accident

I hardly knew him back then, but I knew of him. In the early days of my enthusiasm for racing, I celebrated when he bought a Brabham BT24 at the end of 1968 and had Robin Herd design an installation for a 2.5-litre Cosworth DFW, and then went off with his mate Piers Courage to compete in the Tasman Series at the beginning of 1969.

READ MORE: Sir Frank Williams’ extraordinary career as an F1 Team Principal

Frank was a man who completed others. He’d failed as a racer himself, being too wild and lacking the fine judgement to go really fast. But he knew a good driver when he saw one, and was one of the first to acknowledge the talent of the emergent Jochen Rindt. He loved the Austrian’s flamboyance and pushiness. Having failed as a racing driver, he dealt in racing cars, and travelled Europe with the nomadic F3 circus selling spares. He had a rather uncomplimentary nickname back then, but now things were about to change.

Piers was at a career crossroads, having won F3 races but been turned down in favour of the smoother Chris Irwin for F1 drives with BRM. Like Frank, Piers crashed too often. But that Tasman series was the making of both men. In the beautifully prepared car Piers took a third, a second and a fourth before victory at Teretonga cemented his third place overall behind champion Chris Amon and Jochen.

Piers Courage en route to P2 at Monaco in 1969

Frank and he then stepped into F1 with a Cosworth DFV-powered Brabham BT26, and in a wonderful season Piers finished second to Graham Hill at Monaco and repeated the feat after ousting the works Brabhams in the lucrative US GP at Watkins Glen, where he joined his great friend and racewinner Jochen on the podium.

The following year Gianpaolo Dallara created the de Tomaso 505/38 for Frank to run for Piers, and there was one poignant moment at Monaco, as they had begun to make some progress, when Frank watched Piers and his young wife Sally celebrating with Jochen and Nina Rindt, thinking to himself how young they all were and how it was all too good to be true. Then Piers was killed in the Dutch GP in June, and for a devastated Frank some things were never the same again.

TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY: The Story of Sir Frank Williams

He soldiered on, running Marches in 1971 and ‘72, then building his own cars. First there was the ill-fated Len Bailey-designed Politoys, then a series of Isos built with money from the Italian car company and Marlboro. It was hand-to-mouth stuff, but Jacques Laffite helmed one of his cars to second place in the 1975 German GP. Buying the Hesketh 308Cs for 1976 seemed like a good idea at the time, but the season was a disaster and at the end of it sponsor Walter Wolf took control of Frank’s team.

Frank was meant to stay on as his assistant, but playing second fiddle was never his forte. Ironically, the Wolf won the opening race of 1977 in Argentina, but Frank wasn’t there to witness it and was making plans to set up Williams Grand Prix Engineering.

Triumph and Tragedy: The Story of Frank Williams

Though he was a completer of men, Frank himself needed somebody to complete him. That man was Patrick Head, who brought the pragmatic engineering skills that Frank sorely needed. They started with an updated March 761 for Belgian Patrick Neve, but Patrick had completed the design of the neat and conventional FW06 for 1978. The two partners had signed Austrian GP winner Alan Jones, and the no-nonsense Aussie was exactly their type of driver, a guy who called a spade a spade and might even have used the utensil to fend off critics.

In 1979, in Patrick’s FW07, which was effectively a much better engineered version of the ground-effect Lotus 79 concept, Jones took Williams to the forefront. Ironically, it was Clay Regazzoni who scored Frank’s first victory, in the British GP at Silverstone, but only unreliability prevented Jones from becoming world champion that year. That was rectified in 1980 when driver and team scooped both titles, and they took the 1981 constructors’ title too after Carlos Reutemann wavered in the final race and Nelson Piquet pipped him by a point.

READ MORE: ‘Frank was horrified when he first saw me’ – Patrick Head reflects on Williams' origins

Williams went on to ‘complete’ other racers by turning them into racewinners and world champions: Keke Rosberg in 1982; Nelson Piquet in 1987; Nigel Mansell in 1992; Alain Prost in 1993; Damon Hill in 1996; Jacques Villeneuve in 1997. There was a dip when Honda decamped to McLaren in 1988, but the new partnership with Renault restored the winning ability in 1989, and along the way the team fought honourably against great names such as Ferrari, McLaren, Lotus and Brabham. Altogether they won 114 races and nine constructors’ World Championships too.

And yet, Frank remained a cautious man to whom the next race was the one that mattered most. I remember interviewing him at the end of 1996 when his car had been dominant, and being shocked when he said, “Yes, but we could fall flat on our faces next year.” After the season they’d just had? It seemed impossible, but he was all too aware of the strength and wealth of the Ferrari/Michael Schumacher alliance, and always had massive respect for the way, as he would put it, that Ron Dennis “could always see five years into the future whereas I’m lucky if I can predict what will happen in two.”

Sir Frank admired Ron Dennis' ability to anticipate events

And it turned out he was only a year out in his pessimistic prediction. Williams fell from grace in 1998 after Renault had pulled out, and struggled thereafter until a fresh alliance with BMW took them back to a position to challenge for the 2003 title with Juan Pablo Montoya. It said much of Frank’s wicked sense of honour that, when BMW representatives came over to sign the contract, he waited until his friend, racing driver Robs Lamplough, flew his Spitfire over the factory…

When BMW went to Sauber for 2006 life got harder for the team, but racing was Frank’s life and he never gave up. It was wonderful to see him and his family – wife Ginny and children Jonathan, Claire and Jaime – all together in Barcelona in 2012, when the tempestuous Venezuelan Pastor Maldonado scored a sensational and, as it transpired, final victory for the team.

Frank was not an easy man at times, and he never mollycoddled his drivers. In 1983 he halved Jacques Laffite’s salary; in 1992 he refused to offer Nigel Mansell a better deal, and was quite happy to lose Alain Prost if it meant getting Ayrton Senna for 1994; in 1997 he let Damon go in favour of Heinz-Harald Frentzen. In 1991 I was disinvited from some function, after writing a critical editorial in Motoring News after the way in which he had messed our mate Al Unser Jnr round in a test. Frank made me stay behind after a media get-together at Monza, to administer the metaphorical caning for cheekiness. But the froideur never lasted long.

Williams’ steeliness resulted in Nigel Mansell departing the team in 1992 after winning his drivers’ title

Two years earlier at the same venue, I had glimpsed the inner Frank Williams. A friend had been paralysed in a car accident, and I asked him to give me a 101 lesson in the subject. Three months later I was with that friend in Stoke Mandeville and he was radiant.

“Guess who came to see me yesterday?”

It had been Frank. He didn’t know my friend, but they shared the same consultant and Frank had paid a visit just to offer this young man advice and encouragement. Frank’s thoughtful kindness meant the world to him.

Daughter Claire would eventually take over running the team with Mike Driscoll until the Dorilton buy-out in 2020. The last time I saw Frank was at Spa in 2019 when I had lunch with Jonathan at Williams just as Anthoine Hubert’s accident occurred. We had a good talk, mainly about old times and people and family, and it remains a treasured memory.

Sir Frank Williams CBE LH was a motorsport giant, without question one of the most valiant and committed men our sport has ever produced.

Sir Frank Williams: 1942-2021

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Feature INSIGHT: What it feels like to complete a high-speed lap around Monaco’s famous streets

News ‘Liam helped me massively’ – Hadjar praises team mate Lawson as he hails ‘perfectly executed’ Racing Bulls strategy in Monaco

News Bortoleto unhappy with ‘risk’ Antonelli took that resulted in crash after ‘embarrassing’ overtake

FeatureF1 Unlocked 5 Winners and 5 Losers from the Monaco Grand Prix – Who gambled and got lucky around the streets of Monte Carlo?