Technical

TECH TUESDAY: The ground-breaking Brabham BT52

Share

Thirty-five years ago Nelson Piquet became the first turbo-powered world champion, driving Gordon Murray’s beautiful BMW-engined Brabham BT52. In a special retro feature, Mark Hughes remembers this iconic ‘dart of pleasure’…

The BT52 has gone down in history as one of the most original and iconic of all F1 cars. But its simple dart-like contours – with the radiators sited well behind the cockpit, giving a pencil-thin front and a fanned-out rear – came as Murray’s practical response to an 11th hour regulation change.

As a result of massively increased cornering speeds and G-forces, the sport’s governing body was intent on banning ground-effect cars for 1983 - but even into the 1982 off-season the British teams were fighting this. Brabham’s owner Bernie Ecclestone was leading this resistance and had confidently told Murray to design a ground-effect machine for ’83. This was almost complete when the bombshell came from the FIA in November that flat-bottom cars were to be regulated in from the start of ’83. So the ground-effect BT51 was shelved and in the space of just six weeks, the totally new BT52 was conceived and built. The first race was at Rio, Brazil on March 13th – and Piquet won.

Nelson Piquet won the 1983 drivers' title in the BT52 - a car conceived and built in a scarcely believable six weeks. Note the ultra short sidepods, with the radiators pushed as far back as possible to put more weight over the rear axle and improve traction. © LAT Photographic

Because the flat bottom regulations outlawed the venturi sections of the floor beneath the sidepods that had featured on all F1 cars for several years (following the original innovation of the Lotus 78 in 1977) and banned the nylon side skirts that had sealed the under-floors to give negative pressure, downforce was drastically reduced.

Murray reasoned the downforce reduction would have an adverse effect on traction – particularly important with a turbocharged BMW motor that could approach 1,000bhp in qualifying trim. Accordingly, he sought to put as much of the car’s weight as possible on the rear axle. Because the sidepod venturis had been banished, the sidepods were no longer needed, and so Murray moved the radiators as far back as possible. He also extended that axle line much further back (giving the car the longest wheelbase of all the ’83 contenders) so as to give a flatter deck to better feed the rear wing.

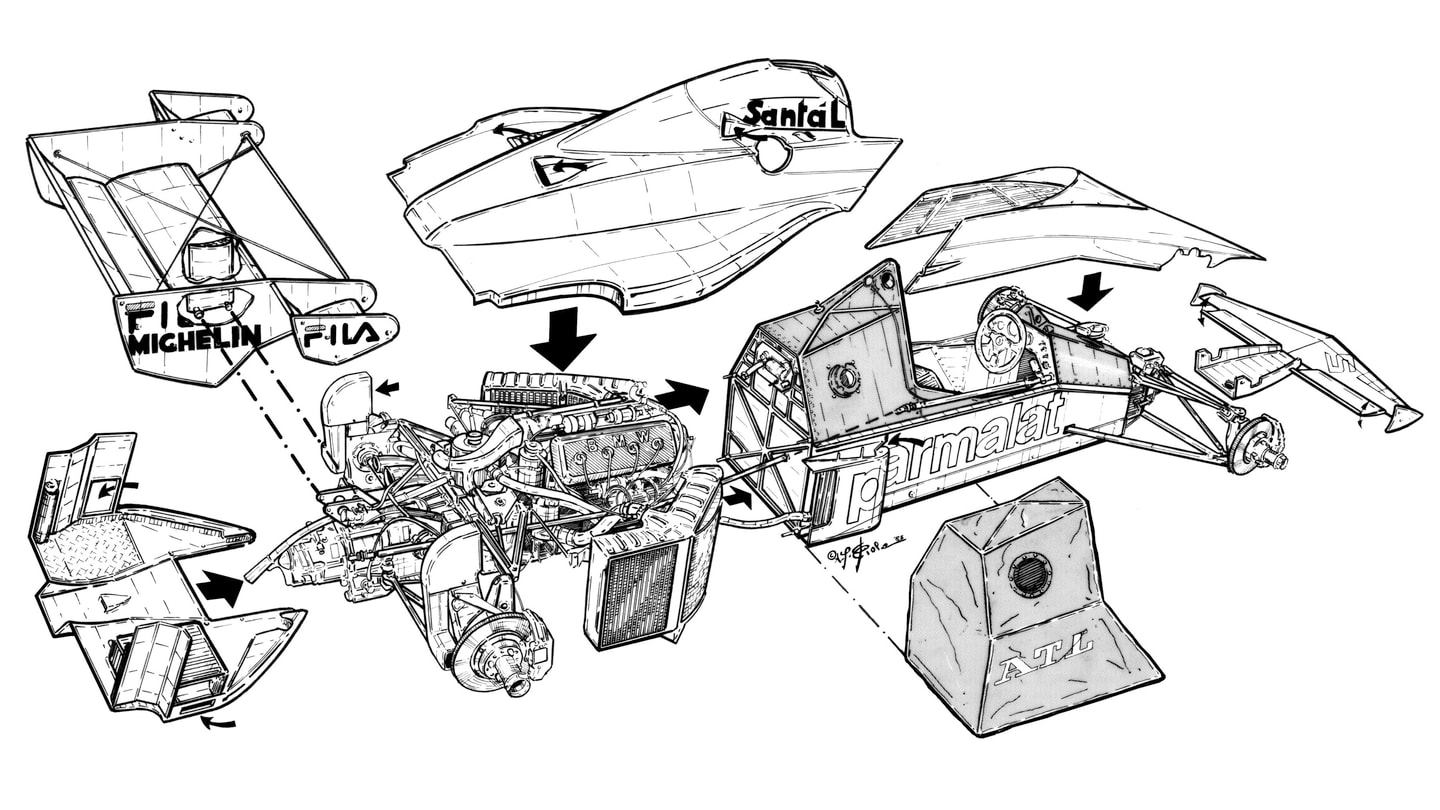

To make the car simple to work on and rebuild, designer Gordon Murray conceived the BT52 in a modular fashion. © Giorgio Piola

The new car also had to incorporate the mid-race refuelling concept Murray had re-introduced to F1 in 1982. Hence it had a less than full-size tank, with a pressurised nozzle system that allowed the fuel to be fed in at up to 5-bar of pressure. In this way, over 30 gallons could be delivered in around 3s. Having introduced this system mid-way through ’82, Murray was certain all the other teams would have copied the idea for their ’83 cars. “I was amazed when we got to Rio and realised that everyone still had these full tank cars,” recalled Murray years later. The smaller tank allowed the car to be packaged better – and created the space that better facilitated the lower engine cover ahead of the rear wing, a crucial part of its aero performance.

Because Brabham was such a small team, Murray paid particular attention to how quickly engine, gearbox and suspension changes could be made. The immensely powerful ‘grenade’ engines used for high-boost qualifying were typically junked afterwards and multiple engine changes per weekend were the norm. Murray created a modular system that was subsequently widely copied. The whole rear end – engine, radiators, intercoolers, transmission, suspension – could be built-up off the car as a single self-contained unit, with liquids all sealed, and then simply bolted into place as required.

At the front, the suspension fed into a single-piece magnesium casting that likewise could be bolted on or off. Spring/damper units were held in place by a pin on the rocker that could be pulled back and released to allow a spring change to be made in a matter of seconds.

)

The BT52 featured a unique arrow-shaped front wing. In contrast to other cars on the grid, including Renault's championship challenging RE40, the driver wasn't flanked by sidepods. © LAT Photographic

The modular aspect of the car’s design and construction can be properly appreciated in the drawing further up the page, showing how the entire rear end bolts onto the bulkhead behind the cockpit. This bulkhead was formed from aluminium, as was the lower part of the chassis, with the upper part in carbon fibre, with aluminium body panels.

Although Murray had been incorporating carbon fibre in his cars’ constructions for four years by this point, he was still reluctant to follow McLaren’s 1981 lead of an all-carbon fibre chassis, given the facilities at his disposal. The underbody diffuser sections (allowed aft of the rear axle) slotted in beneath the gearbox.

“Aerodynamically, it was probably the least adjustable car of all time,” recalls Murray. “We just had front wing flap adjustment to balance it out.”

However, the BT52 proved well balanced and powerful enough for a vivacious Piquet to win three of the 15 races, surrendering a fourth victory in the final round at Kyalami to team mate Riccardo Patrese as he clinched the championship from beneath the noses of Renault and Alain Prost.

And you could argue there hasn't been a more beautiful title-winning car since...

Brabham's principle rivals in 1983 couldn't have produced more different looking machines - Ferrari's 126 C2B was lean and muscular © Sutton Motorsport Images

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Report FP1: Norris tops first Japanese GP practice as Tsunoda debuts for Red Bull

News ‘It’s been quite a challenge’ – Sainz gives his honest reflections on first Williams outings

News Tsunoda’s former boss hails ‘360 degree’ improvement from Japanese driver as he reveals the quality that will help him succeed at Red Bull

News Russell admits surprise at pace of Mercedes’ car as he predicts ‘interesting test’ for team in Japan

)