Technical

TECH TUESDAY: What has made the difference in Renault and Haas’ battle for fourth place?

Share

The battle for fourth place in the constructors’ championship – the unofficial ‘best of the rest’ position behind the big three – has been closely fought between Renault and Haas. But ahead of the season finale in Abu Dhabi, Haas’ boss Guenther Steiner had already flown the white flag on the battle with their rivals, his team sitting 24 points off Renault as they head to Yas Marina.

It’s an interesting contest in that it has been between two teams of very different structure. Renault are a works team manufacturing their own car and power unit, whereas Haas utilise the most extreme interpretation of the listed parts regulation in creating their car. Built by Dallara, with Ferrari mechanicals and running gear, the VF-18 is developed in the Ferrari wind tunnel. Aerodynamicists from Maranello seconded onto the Haas project helped create the car’s concept, with Haas’ own aerodynamic department, operating out of Dallara, then developing it through the season, albeit still using the Ferrari tunnel.

Haas use a completely different technical structure to Renault to field their cars

The Haas F1 project is staffed by not much more than 200 people, whereas Renault’s UK Enstone base is nudging towards 700 (with hundreds more at Viry in France on the power unit side). The end result of these very different set-ups and processes has been two closely-matched cars, the Renault R.S.18 and Haas VF-18.

Renault’s biggest advance over 2017 has been in their reliability. In 16 of the 20 races of the season to date, they’ve scored points with at least one car, and on seven occasions with both. Haas have scored 13 times, and only three times with both. This essentially is what has given Renault the edge, for in raw performance the Haas has more often been quicker.

The Renault and Ferrari power units share a similar layout, with a conventional combined turbo/compressor unit hung at the back of the engine (in contrast to the split compressor/turbines used by Mercedes and Honda). There are packaging pros and cons to each concept, but that of Renault and Ferrari has allowed both the R.S.18 and VF-18 to have the engines slightly further forwards in the chassis than is possible with the alternative layout. This creates the scope for a more accentuated coke bottle profile for the lower bodywork between the sidepods and rear axle line. This helps aerodynamically, as the more extreme that in-cut can be made, the greater the airflow along the flanks is accelerated.

1 / 2

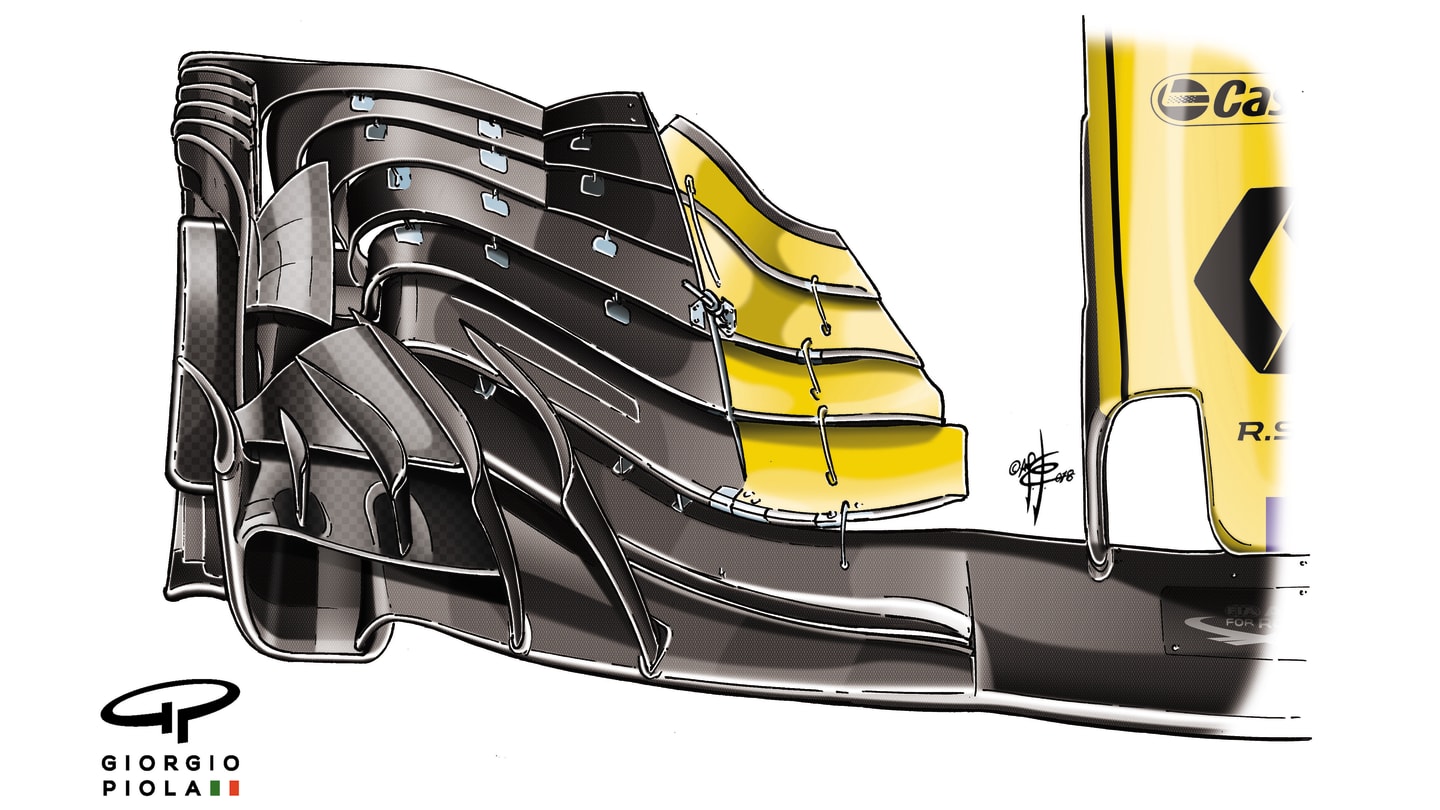

However, it would appear that the less bulky ancillaries of the Ferrari power unit allowed Haas to create a slightly more tightly-packaged rear end. The two cars are similar in wheelbase – Haas obliged to follow Ferrari’s lead in increasing it from 2017 as they use Ferrari’s gearbox – but differ significantly in front wing and barge board philosophies. These were areas of extensive development on both cars, but unchanging was how the Haas surrendered less of the wing’s width to extensive endplates. These endplates are powerful tools in getting the air to outwash around the front tyres, with vortices created by the various body surface interfaces then used to pull the out-washed air back in, to be accelerated along those flanks.

But there is only so much regulation width to the front wing – and any of that width taken up with endplates is not available for the conventional wing, which is creating front downforce conventionally from its multiple elements. The Renault typically used significantly more of the wing’s width for endplates than did that of the Haas. It suggested the Renault’s design may have needed more help from the endplates in accelerating the flow down the body sides. The downside of the reduced width of the conventional wing elements is that they will need to be angled more aggressively to generate a given level of downforce – and will be therefore more draggy and stall-prone.

Renault went big on front wing endplates, which could have hurt them in high-speed corners

The Renault tended to work best on stop/start type circuits and would typically lose out – notably to the Haas – on long, fast corners. The Renault typically would lose time with excessive understeer on such corners. Because there is always a compromise to be made with any F1 car between slow-corner response and fast-corner stability, it suggested that on circuits with a big spread of corner speeds, the Renault could only get slow-corner response from a front wing angle that was then beginning to stall at higher speeds. The narrowness of the main element could certainly have been a contributor to this trait.

Both teams followed the high-rake path popularised by Red Bull. It’s a concept that requires quite a softly-sprung rear end (so that the rake reduces with speed, as downforce presses the rear down to reduce drag on the straight). Renault worked hard through the season in getting the required suspension control, and this was a key to achieving a better compromise between slow and high-speed bends. Using Ferrari’s suspension, the Haas did not seem to suffer the same difficulty. The Ferrari engine also offered a power advantage, especially from Austria onwards, Maranello apparently on a stronger improvement curve with its motor than Viry. This in turn would allow Haas more scope to use wing level to achieve a good balance, with less of a penalty in straightline speed.

Both Renault and Haas used high-rake concepts, but Haas' 'off the peg' Ferrari rear suspension appeared to give them an advantage

Although the Haas’ performance was frequently impressive, two of the team’s biggest points losses were rooted in its small staff numbers. The double retirement in Australia from identically cross-threaded wheel nuts of the cars of Romain Grosjean and Kevin Magnussen came from a lack of pit stop practice during the winter, as everyone was flat-out readying the cars in time. The Monza disqualification for floor dimensions came as a result of the team not being able to produce in time a new one meeting the requirements of a technical directive issued just before the summer break.

It would probably be fair to say that the Haas had slightly more ultimate performance within it than the Renault – but the latter team more consistently and reliably extracted the most out of what it had.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News ‘It’s all to play for’ – Albon 'trying to get my head around' Melbourne points haul as he hails Williams improvements

News Verstappen reflects on late-race Norris battle and ‘spicy’ tyre gamble as he hails ‘decent starting point’ in Australia

Report F3: Camara dominates wet Melbourne Feature Race

News F1 confirms 2026 Concorde Commercial Agreement signed by all teams