Feature

TREMAYNE: John Hugenholtz – the circuit designer who made Suzuka his 'magnum opus'

Share

The recent Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort brought the name of John Hugenholtz back to mind, as the putative designer of the seaside track and also of Suzuka, where the upcoming Japanese Grand Prix will be run.

But who was he, and why do recent lines of thought suggest that he was not, in fact, actually responsible for Zandvoort’s layout?

READ MORE: 'We need a perfect weekend' – Verstappen weighs up title chances on return to Suzuka

Johannes Bernhardus Theodorus Hugenholtz, often called Hans by his family, was born three months after the outbreak of World War I on October 31 1914, in Vledder, a town in the Drenthe province in the north-east of the Netherlands. His father Johann was a minister and a passionate activist for peace, and after relocating to Purmerend in 1918 the family moved again, to Ammerstol in 1924.

Young John, as motorsport came to call him, was more interested in motorcycles and cars, and though he trained to become a lawyer he eventually took up journalism. He wrote about motorsport, transport and technology for several newspapers.

He had started racing motorcycles as an amateur by the age of 22 in 1936, when he founded the Nederlands Auto Race Club (NARC). He had been an enthusiastic spectator when the TT races were held in Drenthe (where today the Dutch GP is held in Assen), but gravitated to Zandvoort, the seaside town also in the north. It was occupied by German forces during World War II, and it was on some of the roads built by a Nazi group that the first Zandvoort track was drawn up by a small group once hostilities had ceased.

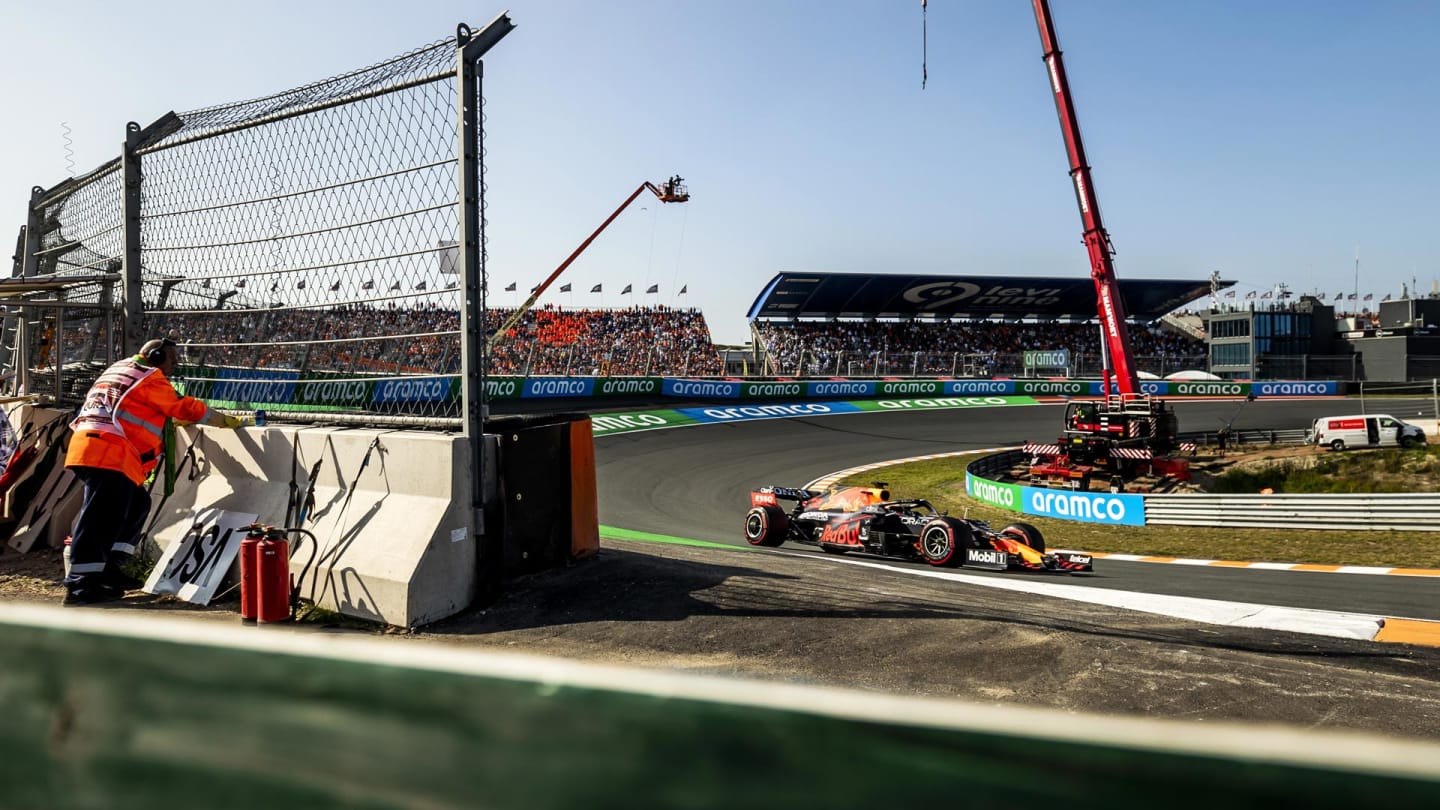

The banked Turn 3 – named after Hugenholtz – at Zandvoort

It is thought by some that Hugenholtz later received the full credit for designing the track that eventually came to be built, possibly because of his relationship with the local mayor which saw him appointed track manager. He would hold that position from 1949 to 1974.

Some sources actually list the architect as Jarno Zaffelli. But current revisionist thinking suggests that former 1927 Le Mans-winning ‘Bentley Boy’ and journalist S.C.H. ‘Sammy’ Davis, acting as track advisor in July 1946, was responsible, together with a bunch of unnamed officials from the Royal Dutch Motorcycle Association, as they used some of the original roads when they drew up the initial layout that first saw action in 1948.

Be that as it may, Hugenholtz went on to be a prolific circuit designer, a Hermann Tilke of the Sixties. There was Zolder in Belgium in 1963; the Motordrom stadium section of Germany’s Hockenheim in 1965; Spain’s Jarama in 1967; America’s Ontario Motor Speedway in California in 1970, in collaboration with architect Michael Parker; and Belgium’s Nivelles in 1971.

Zolder was generally regarded as a bit of a so-so track, the stadium section at Hockenheim worked well, Jarama was derided initially as a ‘Mickey Mouse’ venue by drivers who back then raced at the old Nurburgring and the old Spa-Francorchamps; and Nivelles was slammed as utterly bland, featureless and far too safety conscious.

Ontario was generally well received, however, and ran the innovative non-championship Questor Grand Prix in 1971, which comprised two heats for F1 and F5000 cars and was won by Mario Andretti in a Ferrari. It later saw NASCAR, Indycar and NHRA drag racing action, too.

Ontario Motor Speedway held the non-championship Questor Grand Prix in 1971

But without question, Hugenholtz’s magnum opus was Suzuka, which he designed in 1962.

Adventurously, he opted for a layout befitting a kid’s Scalextric set, with a figure-of-eight flyover design commissioned and funded by Honda founder Soichiro Honda.

The 3.608 mile/5.807km track goes into the fast 160mph right-hander after the start, which loops through 180 degrees before the swerving series of 130 mph esses that leads uphill through a 90-degree right, to the 120 mph left the flows into the two right-hand curves named after motorcycle star Ernst Degner. Degner 1 is entered at 160mph, while Degner 2 is negotiated at 85mph before the track runs beneath a section of its return leg.

It then takes drivers down to the 40mph hairpin left, which in turn leads through the long, long 180mph right-hander of Turn 12 to the 140mph left at 13 and then the left-hand 115mph swoop of the Spoon Curve prior to the fastest part of the track where cars reach well over 200mph. The once-dreaded 130R left-hander, now generally taken flat around 190mph, is arguably the most challenging part of a routinely challenging track, before the 60mph chicane brings them back to the start-finish straight.

Japan 2005 - 130R - Alonso passes Schumacher

Overtaking is always hard here, though not impossible, and to a man, drivers love it. Hugenholtz might not, after all, have designed Zandvoort. But Suzuka stands as a tremendous testimony to his track creation skills, especially when you consider that his original version did not have that chicane to compromise its flowing, high-speed nature.

Much history has been written at the storied circuit. Intended initially as a test track for Honda’s production cars, it also ran some sportscar and Formula 2 races. Its rival Fuji Speedway ran F1 in 1976 and '77, and again many years later in 2007 and '08, but Suzuka would become the much-loved spiritual home of the Japanese GP when F1 returned in 1987, and the race went back in 2009 and has stayed there ever since.

Hugenholtz was as active politically as he was artistically. In 1956 he created the Association Internationale de Circuits Permanents in Paris, and the Pionier Automobielen Club, which in turn led to the establishment of the Federation Internationale des Voitures Anciennes (FIVA).

WATCH: Prost vs Senna – How the infamous Suzuka '89 clash unfolded

Suzuka returns to the F1 calendar in 2022, after two years away

He was also a safety-conscious man, and came up with a unique system of poles and chain-link fences which were positioned in trackside run-off areas to capture errant cars and bring them to a ‘softer’ halt than hitting an Armco barrier or a concrete wall. Known as catch fencing, this innovative system was a clever solution in the 1970s but met with mixed reviews, especially after a spate of drivers being struck on the head by the support poles, or trapped as the fencing wrapped around their cars, and its use was eventually abandoned.

Ever intrigued by technology, Hugenholtz even ventured into car design. But the Dutch Barkley never reached production in 1948, and the Alfa Romeo-based Delfino, which came 41 years later, was likewise stillborn.

Ironically, given his passion for safety, Fate took him and his wife Marianne Sophie van Rheineck Leyssius in a serious car accident at Zandvoort on January 10, 1995. Marianne died instantly, while Hugenholtz lingered for 11 weeks before succumbing. But as long as drivers race on the tracks he designed or managed, his legacy lives on.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News Opmeer claims victory as F1 Sim Racing World Championship continues in Mexico City

News ‘We have a duty of care to protect and develop Liam’ – Horner opens up on decision to replace Lawson at Red Bull

Podcast F1 EXPLAINS: What it’s like to be an F1 team boss – with McLaren’s Zak Brown live in the paddock

Report Jarno Opmeer and Bari Broumand take victory in Rounds 10 and 11 of F1 Sim Racing World Championship