18 - 20 April

Opinion

TREMAYNE: Superb engineering, great driving and cohesive teamwork – How Red Bull charged to another F1 constructors’ title

Share

Well, it’s happened. Just as we knew it would almost from the start of the 2023. Shrugging off that peculiar fall from grace in Singapore, Red Bull blasted back with full force in Suzuka this weekend to win their sixth World Championship for Constructors (2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2022, 2023) in great style.

The dramas of Marina Bay notwithstanding, miracles were needed for anyone to delay the success here. Red Bull needed only to outscore Mercedes by a single point, while Ferrari had to score 24 more than Red Bull to prolong the battle.

TREMAYNE: Verstappen’s record breaking should be celebrated – it proves F1 has never been healthier

The Scuderia’s success last time out punctured Red Bull’s hopes of winning every race, but in the overall scheme of things that didn’t really matter. The championship is what counted.

The last F1 car to threaten to win all of a season’s races, Steve Nichols’ seminal McLaren MP4/4 of 1988, was a new machine created specifically for the final season of the original turbocharged era.

It’s interesting that the only other car to be so dominant, Red Bull’s RB19, was an evolution of the super-successful RB18 of 2022, and that it was also powered by Honda… Where better then to clinch it than in the engine manufacturer’s own backyard?

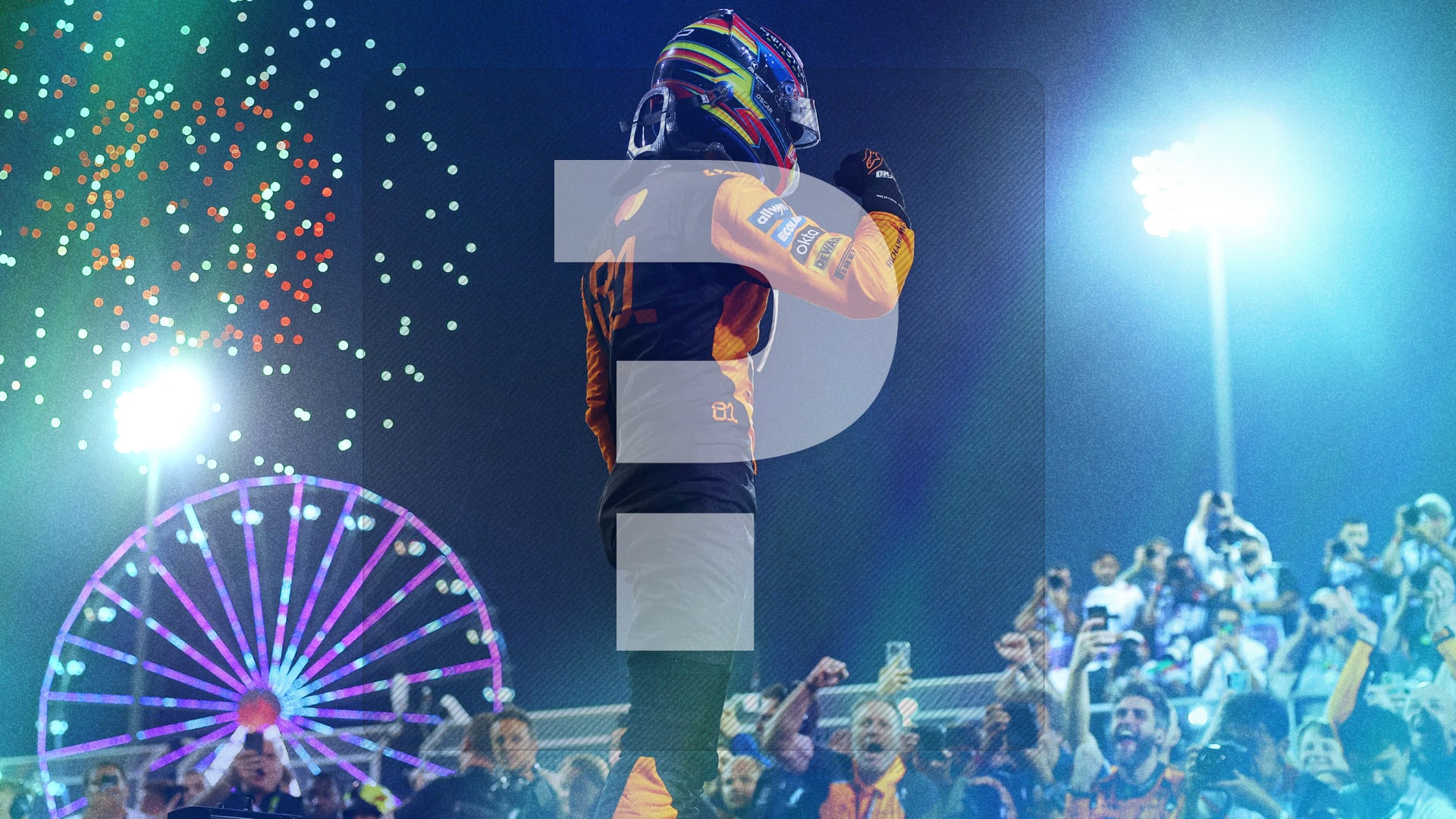

Max Verstappen's victory in Japan helped secure Red Bull's sixth constructors' title

When the rules changed to ground effect cars for 2022, after a year’s delay following Covid, a sport that had become an engine formula with the start of the turbo-hybrid era in 2014 reverted once again to an aerodynamic formula. And in F1, that is synonymous with Adrian Newey. The man who can bend air to his own will. And also the man who had been around, at the start of his F1 journey, back in the early days of ground effect.

That would prove crucial.

Where others either forgot about its various challenges or knew nothing of them – most notably porpoising, when the car lost and regained downforce in pitch – Adrian knew what to do largely to avoid the driver-bouncing phenomenon, and, backed by a motivated and clever aero department chez Milton Keynes, the elegant RB18 was the car of the year. Max Verstappen won an incredible 15 of the races, team-mate Sergio Perez the other two.

And, therein, lay the platform to launch an even better attack in 2023. It was like the good old days, which began in 2009 and culminated in Sebastian Vettel’s reign of aero terror that lasted from 2010 to 2013 in a series of aerodynamically clever and superior Red Bulls with their blown diffusers.

Record-breaking Red Bull Racing clinch the constructors’ championship in Japan

The RB19 sought to correct the RB18’s few shortcomings. Most notably, the latter had been around 20 kg overweight at the start of the season. Hard work had pared that to four before further upgrades saw it creep back up to around 12 by season end.

So much work went into lightening the RB19, which used the same highly successful Honda RBPTH001 V6. With Honda Racing Developments’ MGU-H and MGU-K energy recovery systems its 900+ bhp output rates it as one of the most potent homologated power units.

After a crushing 1-2 in the opening race in Bahrain, a broken driveshaft left Max 15th on the grid in Jeddah and cost him another win, though he demonstrated the car’s level of performance by coming through the field to second behind Sergio. He was soon back on top Down Under, but had to settle for second to Sergio in Azerbaijan. The Mexican won the Sprint Race there as Max could only manage third in a damaged car after an early collision with George Russell. But from then on until Singapore, the world champion was simply unbeatable.

He won in Miami, Monaco, Barcelona, Montreal, Spielberg, Silverstone, Hungaroring, Spa and Zandvoort to equal the nine-on-the-bounce records of Alberto Ascari and Sebastian Vettel, then broke that with a 10th victory in Monza.

Verstappen and Red Bull stretched their winning runs to 10 and 15 races respectively

Once just a point behind him in the overall rankings after the win in Saudi Arabia, Sergio’s form then ebbed and flowed for the rest of the season: fifth in Melbourne; first in Baku; second in Miami; 16th in Monaco; fourth in Barcelona; sixth in Montreal; third in Spielberg; sixth at Silverstone; third at Hungaroring; second at Spa; fourth at Zandvoort; second at Monza; eighth in Singapore. Paddock sources joked that Red Bull would still be leading the Constructors’ stakes purely on the strength of Max’s scores.

So the RB19 was not always an easy car either to set up or to drive, though its inherent aerodynamic excellence endowed it with phenomenal performance when you found the sweet spot. Ninety-nine percent of the time Max did just that, but even he was defeated by its sudden intransigence in Singapore, a track he had not expected to suit it.

There, after qualifying only 11th, he had responded tersely to questions about stretching his winning streak to 11. “You can forget about that. You can't pass. On other tracks you can start last, I mean probably in Spa you can start last and win the race, but not here. Here you need to be two or three seconds faster to have a chance to pass. And so that's just street circuit stuff.

“I knew that there was a day that you’re not winning anymore, but we had a really good run anyway, up until now. I would always take a season like we’re winning this much and having one really bad weekend over the other way around, where you're not fighting for the championship, and then you’re winning here.”

Red Bull have continued to light up race tracks all over the world through the 2023 season

It wasn’t just air that Newey could bend. He is the absolute master of creating carbon fibre components that bend just enough to facilitate greater downforce while staying within the rules. But that didn’t stop some rivals hinting that a new technical directive issued prior to the race had, in some way, hampered the Red Bull more than others.

Explaining TD018, FIA Single Seater Technical Director Tim Goss said: “There are a lot of clever engineers out there looking to get the most out of the regulations and we have to make sure that everyone has a common understanding of where the boundaries are and we have to be fair and balanced across the whole group in how we apply them,” he explains. “And in recent times we have seen a little bit too much freedom being applied to the design details of certain aerodynamic components.”

GREATEST HITS: From perfect pole laps to charging comebacks – Perez’s best moments in F1

In layman’s terms, as Goss explained it, that means that clearer guidance around how components are joined together was needed. “For us, the important bit of Article 3.2.2 is that ‘all aerodynamic components or bodywork influencing the car’s aerodynamic performance must be rigidly secured and immobile with respect to their frame of reference and that they must make a uniform, solid, hard, continuous surface under all circumstances.

Red Bull celebrate 100th F1 win with Verstappen victory in Canada

“Now, quite clearly things cannot be totally rigid. So, we have a range of load deflection tests that define how much elements can bend and we’ve evolved those tests to represent what the teams are trying to achieve on track and to put a sensible limit on them.

“We play by those rules, while teams look to exploit the allowance in terms of deflection. That’s normal. So the TD is just about making sure that we, the FIA, and the teams, all have a common understanding of where we will draw the line in terms of these design details.

TECH TUESDAY: Is this the small design detail behind Red Bull’s massive advantage in 2023?

“It’s not that we’ve seen any one particular car or feature that we’ve targeted, or an element that’s been common across the whole grid,” he says. “This is about where front and rear wing elements join the nose, join the rear impact structure, join the rear wing endplates. And there have been several instances where teams have tried to make the most of the deflection allowance by permitting some bits and pieces to start moving relative to each other.”

While rivals smirked hopefully, Red Bull were adamant their car complied at all times with such rules on flexure. That sort of finger-pointing is common whenever one team is doing a smarter job, and just part of the manner in which the Piranha Club runs. Max’s speed in Suzuka proved conclusively that TD018 had not been the cause of the Singapore problem.

Verstappen and Red Bull were back to their very best at Suzuka as they wrapped up the constructors’ title

Sources within the team suggest that, far from bending the rules the RB19’s excellence comes from its fundamental design and continuous reassessment of even the smallest things, of tremendous attention to aerodynamic detail and the endless search for even the tiniest advantage.

That is also reflected in the beauty of their pit stops. Despite the rules governing them being tightened last year, this year they set a new standing-still record for a tyre change of 1.9s.

Factor in other things, such as Max’s occasionally spiky yet very close relationship with Race Engineer Gianpiero Lambiase, Christian Horner’s capable management and its generally spot-on race strategies overseen by Hannah Schmitz, and a much clearer picture emerges of why the team from Milton Keynes have become the pacesetters since the formula changed.

It also shows how you don’t win 10 races in a row and dominate a World Championship by luck or any other means other than superb engineering, great driving and cohesive teamwork.

Back in 1988 McLaren were often criticised and derided, but the truth then remains the truth today: it’s not their fault they dominated, but their rivals for not being as clever.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Podcast BEYOND THE GRID: Esteban Ocon on why he’s feeling at home with Haas

News Wheatley vows to lead Kick Sauber ‘in my own way’ as he explains challenge ahead of Audi’s arrival

News Bortoleto keen to move on from ‘challenging’ weekend in Bahrain as Hulkenberg reflects on ‘pretty dreadful’ race incident

Feature F1 FANTASY: Strategist Selection – What’s the best line-up for the Saudi Arabian Grand Prix?