Feature

Driving the F1 Medical Car - the world’s fastest ambulance

Share

When a driver hits the barriers at speed, the Formula One Medical Car is on the scene in seconds. But how does a nearly two-tonne car laden with doctors and medical equipment get there so quickly? We spoke to Medical Car driver Alan van der Merwe to find out…

The first track action of a Grand Prix weekend has a rather deeper note than those that follow. On Thursday, usually between 1400 and 1500, the FIA Safety Car and Medical Car take to the track for an hour of high-speed practice. Bernd Maylander’s Mercedes-AMG GT S safety car is a pretty familiar sight for fans around the world - but the Mercedes-AMG C 63 S Medical Car will spend the rest of the weekend in relative anonymity, should everything go to plan.

Anonymity, says Medical Car driver Alan van der Merwe, is what the job’s all about. “We’ll be most visible if we make a mistake - so the biggest part of the job is being as anonymous as possible,” says the 37-year-old, who took on Medical Car duties in 2009.

“We want to be on track as little as possible; when we are on track we never want to shunt the car, or get involved with any of the race cars. There’s a lot that goes into that, from making sure the cars are mechanically right, to how we drive on the circuit to ensuring there is sufficient margin for error.”

And when it comes to driving, Van der Merwe is more than a safe pair of hands - in fact he might well have made it to the F1 grid himself if his career had taken a few different twists and turns. A former Formula Ford Festival and British Formula 3 champion, the South African can count a stint as BAR-Honda’s test driver amongst his racing accomplishments.

Driver, not paramedic…

The Medical Car carries the FIA medical rescue co-ordinator, Dr Ian Roberts, and frequently a local doctor specialising in emergency medicine to the scene of an accident. Extraction teams are positioned around the circuit to deal with these situations, under the supervision of Dr Roberts, who is variously a consultant in anaesthesia and intensive care, a veteran HEMS (Helicopter Emergency Medical Service) specialist and the former chief medical officer of the British Grand Prix. Contrary to popular opinion, the logic of having an experienced racing driver - rather than, for example, a paramedic - delivering the medical staff to the scene, is not based on speed.

“The most important factor is not that you can drive a car fast: there are millions of people who could drive the car fast enough to get to an incident within a clinical time frame where it matters,” says Van der Merwe. “The thing to consider is the environment: you’re driving a big, heavy estate car and sometimes sharing the track with extremely fast racing cars, probably the fastest racing cars in the world over a lap. It’s a difficult combination. It isn’t enough to be driving around close to the limit: you need to be constantly thinking about other people also.

“You need the extra capacity to be driving close to the limit while thinking about what’s ahead, what’s behind. You have to be prepared for drivers making mistakes, marshals jumping over the barrier ahead of you. It’s about having the capacity to drive the car quickly enough to get to the scene, stay ahead of the cars on track while maintaining a huge margin of error to deal with the unexpected.”

The harder car to drive…

The 550hp Medical Car, as Alan suggests is both big and heavy. Powered by a 4-litre twin turbo V8, when fully loaded it weighs in at nearly two tonnes. Watching it circulate in tandem with the Safety Car, it’s obviously rather more of a handful to drive at high-speed than its smaller companion.

“By design the Safety Car is a perfectly-balanced supercar,” he says. “We didn’t need to modify it much, in fact you can buy that specification, minus the FIA safety gear. The Medical Car, on the other hand, is a little bit different. It has to cope with two tonnes of weight when we’re loaded up so it’s extremely stiff and everything we don’t need has been stripped out.

“To get close to the limit in a car like this, you need to be able to push it. On Thursdays I’ll be driving faster than I do throughout the weekend. It’s about getting into a rhythm where I’m comfortable at 98 percent, so that in the race I can drive at 95 percent and be on the radio talking to race control, looking in my mirrors and that sort to thing. You’ve got some capacity in reserve, and so does the car. You don’t want to be at 100 percent so that when something strange happens, there’s no exit option.”

Dishing out punishment

In common with the F1 cars, the Safety and Medical Cars have their own garages, usually at the start, sometimes the end, of the pit lane where a crew of AMG mechanics tend to them. The nature of the job ensures the cars take a lot of punishment, particularly, as Alan says, at the start of the event when the drivers want to test the conditions and so push hard, ride the kerbs and find the limits.

“We do punish the cars on Thursday,” says Alan. “The AMG guys want to see how the cars cope mechanically, and we need to find out how the tyres are holding up. Somewhere like Sepang, for example, in those temperatures you can’t pound around endlessly: we can do maybe two or three laps and then things start deteriorating. Essentially it’s still a road car and when we’ve got it fully stocked with gear in the back and three people in it, it’s under a lot of load.”

The back-up plan

A frequent question fielded by Bernd Maylander and Alan van der Merwe is what happens if one of their cars fails? The answer is rather more mundane than many people expect: AMG bring two of each and the drivers use them in rotation according to tyre mileage and brake wear. Failures are incredibly rare - but they do happen.

“We had to swap cars after the first lap at Silverstone in 2015 - but I don’t think anyone noticed!” says Alan. “We take the two Medical Cars to every race, I don’t think anyone outside could tell them apart but, because we spend so much time sitting in them, I know which is which. We have a primary car for the weekend and only run the back-up for the track test in the mornings, to make sure the tyres are bedded in and the thing’s ready to go if necessary.

“At Silverstone we had a tyre failure. I felt it about halfway around the lap and we had to crawl back and quickly swap cars. These things happen - it all went to plan and was very well orchestrated. I think our car is the one that gets the biggest beating out of all the service vehicles because it’s driven through all sorts of rubbish on the track and we hammer it over kerbs all weekend and it goes from sitting in the pit lane fairly cold - to flat out, trying to stay in front of Bernd, so it gets a hammering. One failure in seven years is pretty good!”

Always on call

The track test, together with reconnaissance laps ahead of each running session and the first lap of the Grand Prix (where the Medical Car follows the pack around before pulling into the pits) is the most visible part of the job - but it’s a busy weekend around that for the Medical Car crew. They cover the GP2/GP3 sessions also, and other series as requested, and thus attend a lot of driver briefing sessions, and whenever cars are on track, they’re sitting with the engine running at the end of the pit lane, permanently ready to go. Like the rest of the world they see the live TV feed - but they also have extra data feeds supplied by race control, such as the GPS track map and the alerts transmitted from the cars on track, registering impacts and their severity. The latter is vital for the doctors, allowing them a little lead-time in formulating their response when they receive word from race control to proceed onto the track.

No heroics

Over a race weekend a track ‘evolves’, with grip improving on the racing line as rubber goes down but also as the line is cleaned by the passage of cars. This is particularly prevalent on street circuits, as normal roads are considerably dirtier than permanent circuits. By virtue of being first on track, the Safety and Medical Cars experience the track at its absolute worst, and so, in the role of guinea pig and despite vast experience, the drivers tend to approach the session with a lot of caution.

“Somewhere like Baku (a lap of which you can see in the video above) or Monaco, you could go out like a hero - but clip a wall and you’ll destroy a road car quite easily. There’s no grip, it’s dirty, and Baku was also quite oily because the tarmac was new, so you build up slowly. You go out and chip away. We’re not going to prove anything by being five-tenths quicker a lap. Nobody cares. It’s not important.”

At the scene

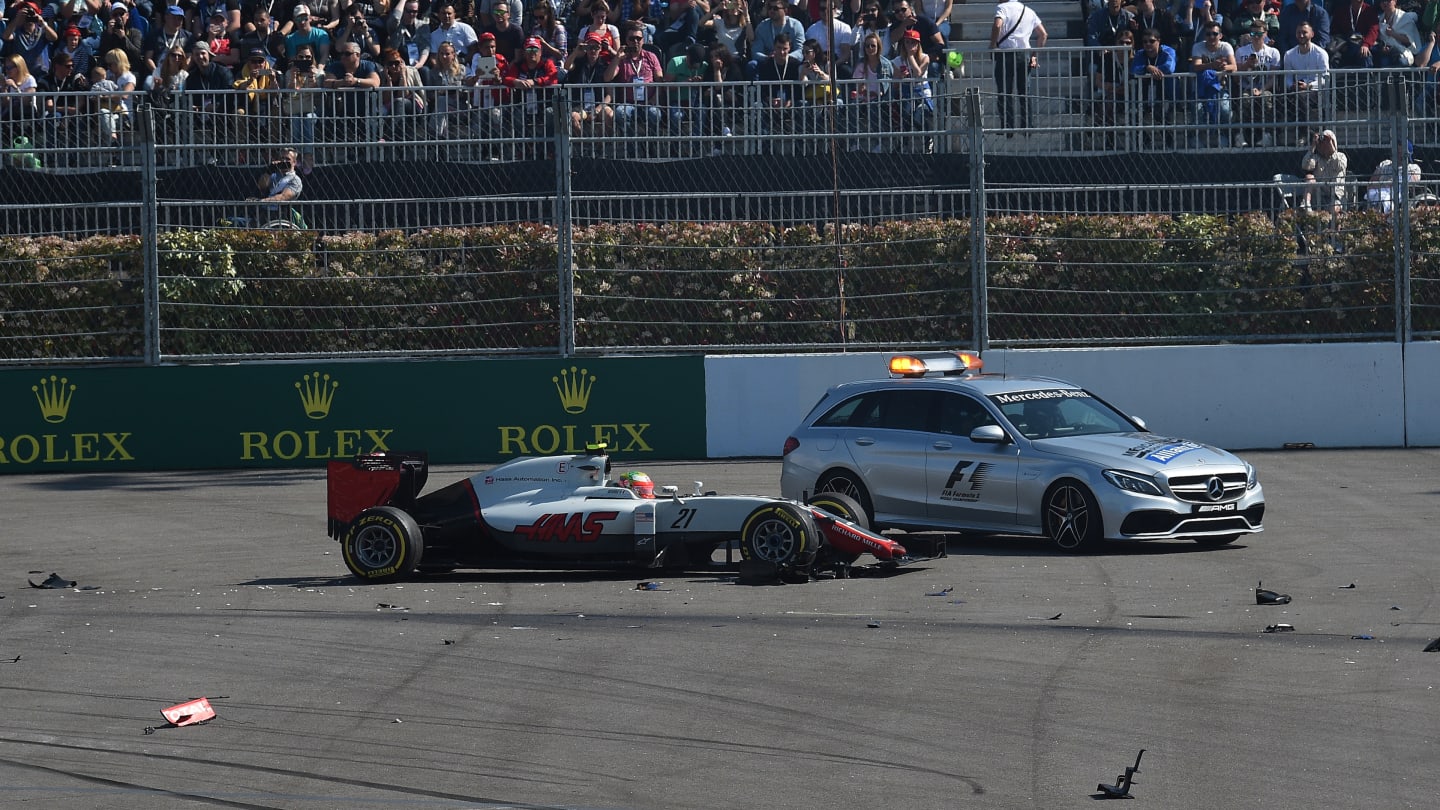

Van der Merwe’s job at the scene is to be an extra pair of eyes and ears, and also, where circumstances dictate, an extra pair of hands. As at a road-traffic accident, the car is parked to protect the people working at the scene, after that the job is to assist the recovery operation.

“A lot depends on the experience of the crews coming to the scene. You have to make sure recovery vehicles have good access, ambulances might require some direction because they won’t be experienced with race tracks and you don’t want anyone stuck in the gravel. The doctors may need one of their kitbags bringing if they’re rushed to the scene. My job is essentially to read the situation, make sure everyone has what they need, direct the arriving vehicles if necessary and generally help out. If I’m not needed, I stay in the car. I can talk on the radio and inform race control of what’s going on with Ian if he has his hands full.”

Share

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

News Alonso says Aston Martin ‘need to get used to’ not scoring in 2025 as he reflects on dramatic near-miss with protégé Bortoleto in Jeddah

Feature The ‘important’ lessons F1 is learning from the development of sustainable fuels in F2 and F3 ahead of 2026

Feature Theme park fun, discos with Russell and architect dreams – Getting to know the real Kimi Antonelli

News ‘One of my most difficult days in Formula 1’ – Doohan pinpoints area for improvement after challenging Saudi Arabian GP