Feature

The lost champion? Jackie Stewart on ill-fated protégé Francois Cevert

Share

Alain Prost remains France’s only world champion – but had fate not intervened, they may well have had two. 45 years since the world lost the glittering talent that was Francois Cevert, we ask his former team mate and mentor Sir Jackie Stewart about the pair’s unique master/student relationship, and find out why he still thinks Cevert would have been France’s first champ.

The classic, archetypal image of the Formula 1 driver is, by and large, a myth. Model looks, humble, charming – yet able to slip into a racing car and push it to its mechanical limits, spray the champagne on the podium, then finish off the evening at the baby grand in the bar, playing some light Chopin.

Few have ever approached the ideal. Jean Alesi is still idolised today for nearly nailing it, while the likes of Peter Collins, Elio de Angelis, Alfonso de Portago and Peter Revson all skated around it. But Francois Cevert fulfilled the role to a tee.

Cevert debuted in Formula 1 midway through 1970, subbed into the Tyrrell team alongside Jackie Stewart. The complete sponsor-friendly package, Cevert boasted looks, charisma, humour, humility. And as a classically-trained pianist, he could even do the Chopin…

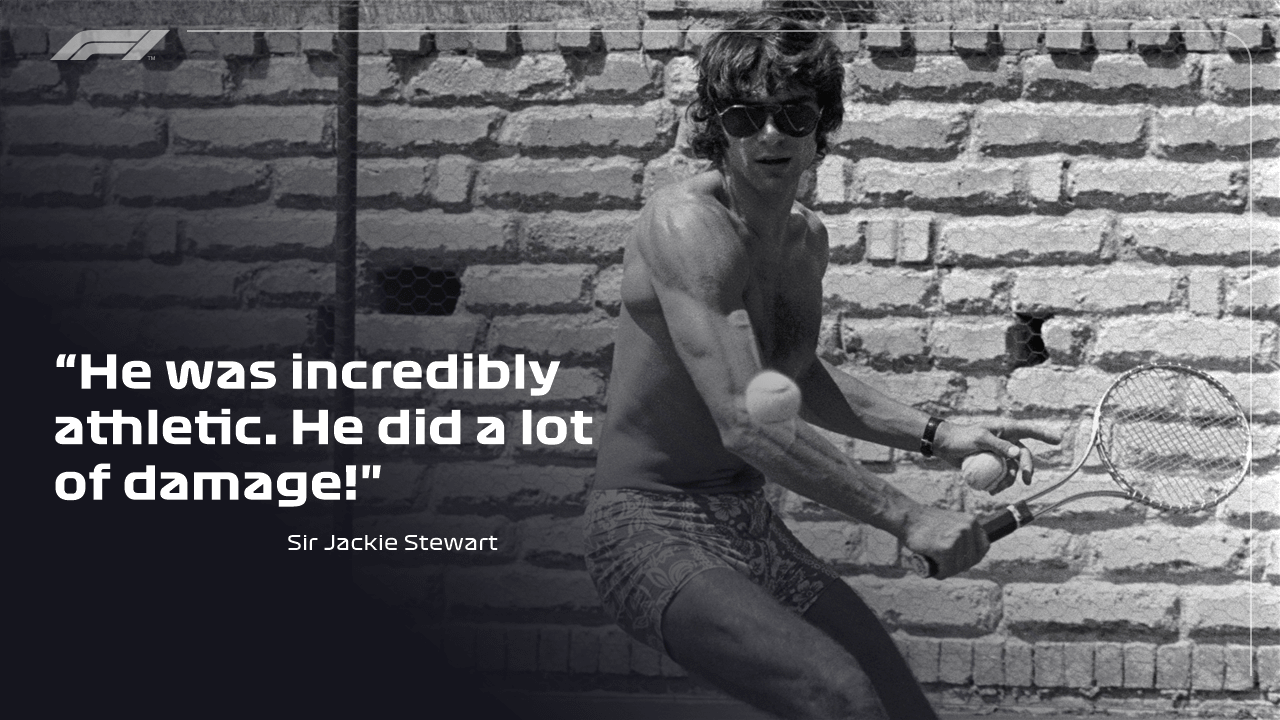

“He was an incredibly good looking man,” remembers Stewart today. “Incredibly athletic, a very good tennis player, good table tennis player… A charming person with impeccable manners. I mean, he did a lot of damage!”

But although he’d been a front-runner in all the lower formula he’d raced in, arguably the only thing Cevert was missing was a true, great natural driving talent – and that’s where Stewart came in.

“He came in as a Formula 1 rookie,” says Stewart, “and from that point on, I took him on...”

Master/pupil

Stewart had first become aware of Cevert’s skill while judging the best drivers in the Renault Elf Winfield Racing School at Paul Ricard in 1967, alongside Ken Tyrrell.

“Francois was probably the prime pupil,” he recalls. “We had put him down as one of the potentials for the future, but not to drive a Formula 1 car, by any means, at that time.”

Stewart and Cevert later raced each other in a Formula 2 outing at Reims in 1969 – Cevert winning that encounter as Stewart finished fourth – before in 1970, Cevert unwittingly auditioned for a place in the Tyrrell team.

“Ken called me, because Francois was driving at Crystal Palace and he asked me to come along to see him race,” says Stewart. “I was living in Switzerland at that time, so I went over specially to see him race there. And that was the decision day as to whether we were going to have him as a second driver.”

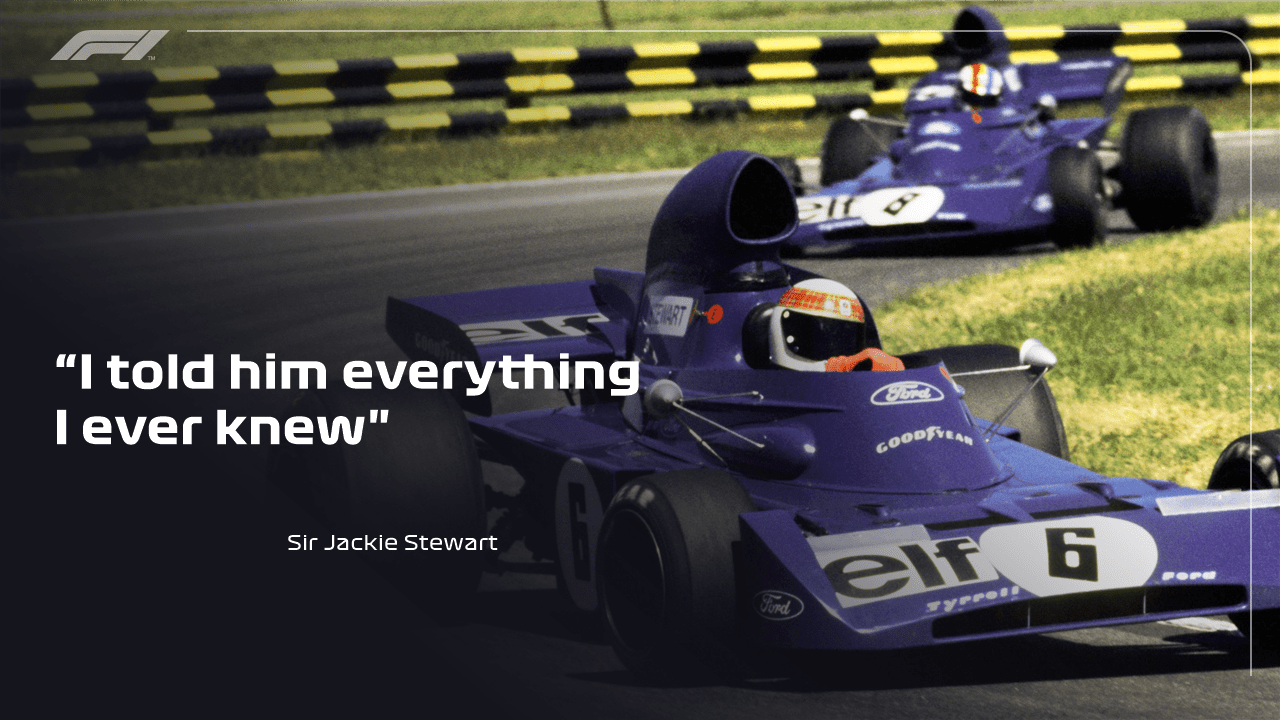

Cevert, bright-eyed, eager to learn but by no means a nailed on world champion of the future, was taken wholly under Stewart’s wing – first at the request of Ken Tyrrell, but the two men quickly formed a master/apprentice relationship the likes of which Formula 1 has rarely, if ever, seen since. “Dieter Quester crowned it as the professor and the student and that's what it was,” says Stewart. “I told him everything I ever knew… There was never a time when I would have said, 'I'm not going to tell you that’.”

In the pair’s early days together, Stewart would often drive around in practice with Cevert in his wheel tracks, ducks-and-drakes style, showing him the right lines to help him qualify for the race.

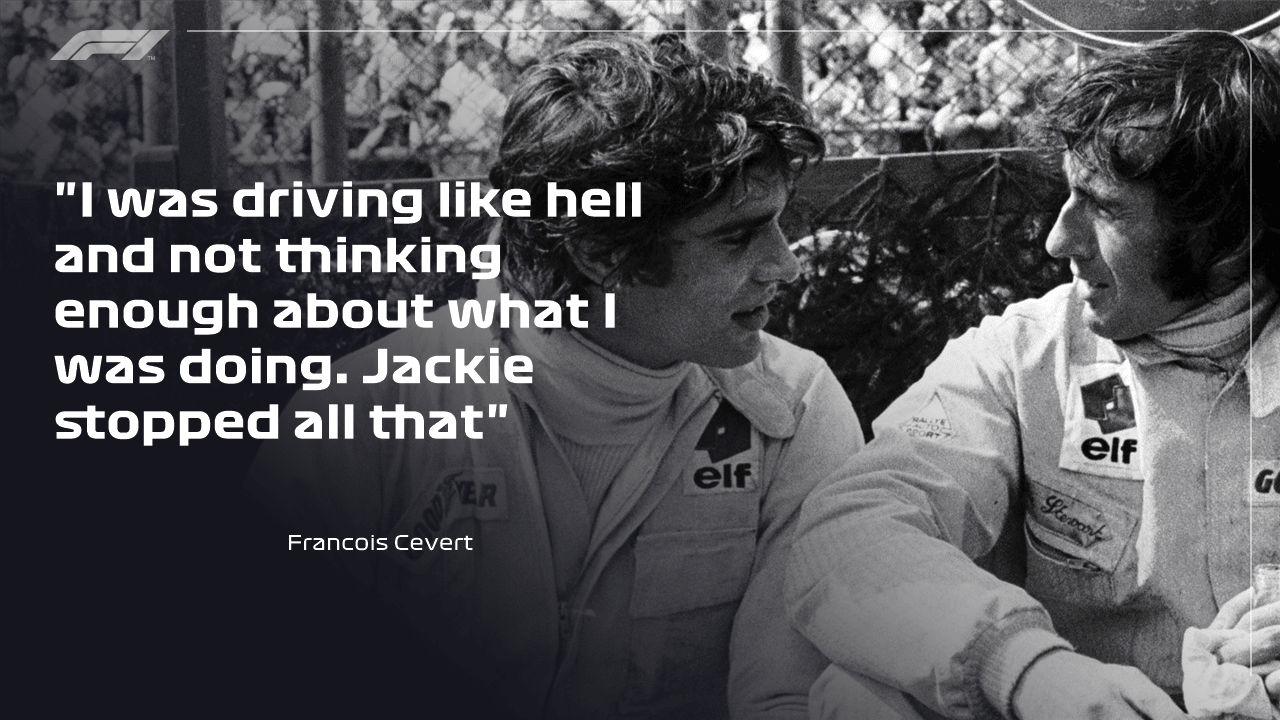

For his part, Cevert never shied away from his apprentice status, or felt disempowered by it. “It’s very simple,” he says in an interview from that era. “Jackie did all my education.

"I was driving like hell and not thinking enough about what I was doing. Jackie stopped all that and taught me how you must analyse a car, how you must think when you are driving, the vision you must have. He did all my education… Jackie is still the maestro for me.”

The crash

Stewart and Cevert’s master/pupil relationship continued all the way through from mid-1970 to 1973, Cevert asking the questions, Stewart answering them, spilling the precious pearls that had made him the driver to beat in that period.

Cevert failed to win a race in 1973 – his only career triumph having come at the 1971 United States Grand Prix – but followed his team leader home three times that season as the pair learned to master their twitchy, tough-to-drive, short-wheelbase Tyrrell 005s and 006s. Then, with Stewart already crowned world champion for a third time, came the season finale at Watkins Glen in New York State, Stewart’s 100th race and, unbeknownst to Cevert, the one he planned to be his last.

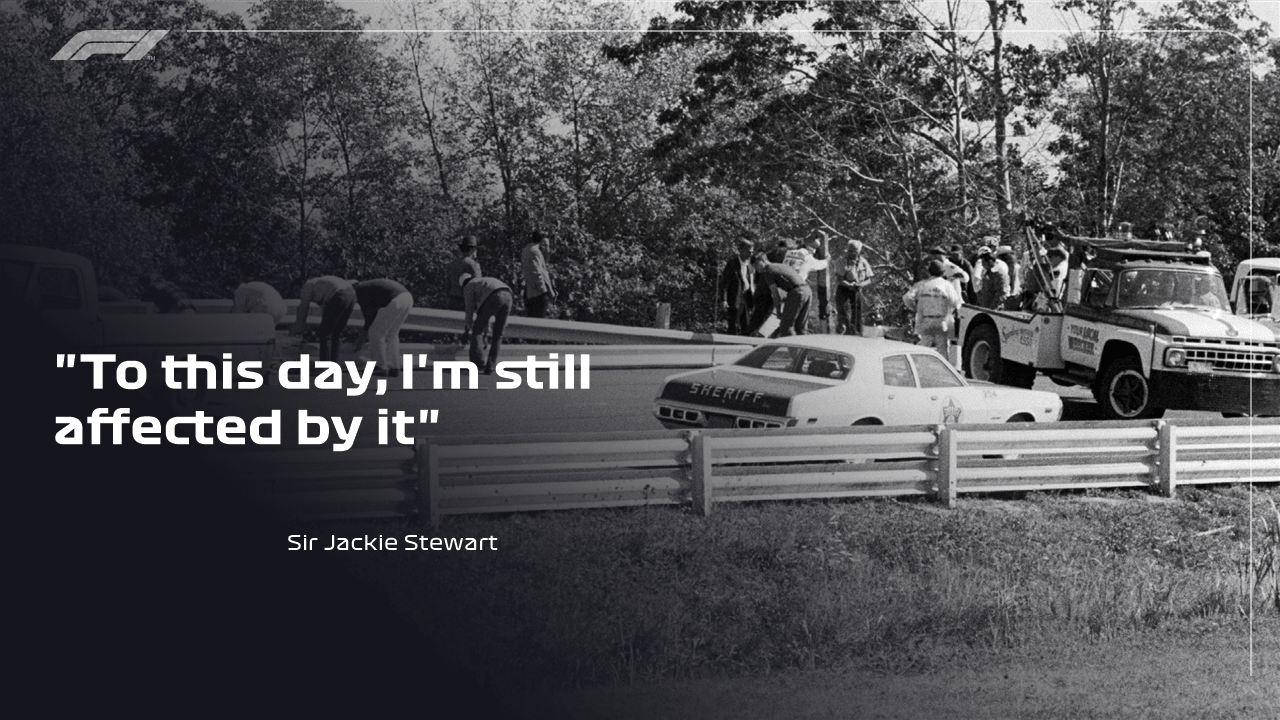

Cevert headed out for qualifying on Saturday. Going through the track’s fast, uphill Esses section, his car left the road and hit the right-hand side barrier before slewing back across the track and coming to rest upside-down on the left-hand side barrier. With the remains of Cevert’s wrecked Tyrrell blocking the track, the drivers behind all stopped, got out and went to see if they could help. All were horrified by what they saw.

“Chris Amon was driving for us at that race,” Stewart remembers. “I saw the blue debris and then I saw Chris walking across the track. I put my thumb up to him to say, ‘Are you okay?’ All he did was put his finger up and shake it back and forward, to say ‘It's not me’, obviously. And then there could only have been one person.”

Cevert was dead at 29. And though no one could possibly have saved him after the sickening violence of his crash, Stewart was haunted for years by his decision to drive slowly back to the pits rather than remain at his friend’s side. But after so many years, had Stewart managed to reconcile himself to his role in the aftermath of the crash that day? His voice drops.

“Not really,” he says. “To this day, I wish that I'd stayed longer with him. But he was dead. It was a horrendous accident, far beyond anything I think there's ever been in a Formula 1 race. I mean, it was just horrendous. And to this day, I'm still affected by it.”

He’s not the only one.

“Jody Scheckter, to this day, is hugely affected by it – to this day. It was a terrible sight and the worst possible thing to happen… and certainly the worst part of my entire career.”

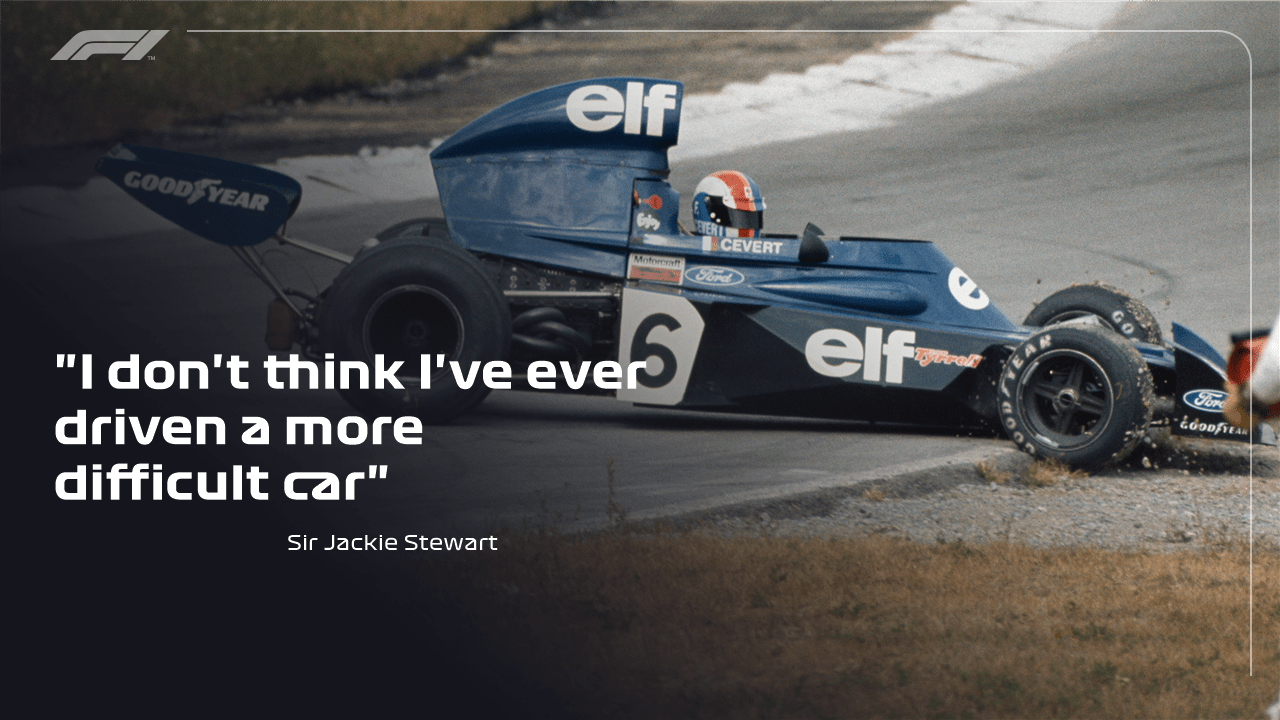

Stewart remains certain that Cevert was running a gear lower than he was through that part of the track that day, and that it was that, coupled with the twitchy handling of Cevert’s short-wheelbase 006, that cost the Frenchman his life.

“I don't think I've ever driven a more difficult car,” he says. “It was very fast, but very difficult to drive. I don't think many people could have won with that car actually.

“I’d worked out that I could go through [the Esses in fourth gear] – maybe a little bit slower but I was still sort of pole position speed. But in third gear, the car became so nervous. And in Francois' case, I am absolutely convinced... that that overly nervous, short-wheelbase car, being driven as quickly as he could drive, whiplashed and hit the barrier on the right-hand side… It had nearly happened to me and that's why I went up a gear.”

Throughout the 1973 season, Stewart had been busy developing the following year’s Tyrrell, the 007, a longer wheelbase machine designed to eradicate the 006’s twitchiness and create a more consistent, less edgy car. Does Stewart dare to think that, equipped with the 007, Cevert’s accident might have been avoided?

“I'm pretty certain,” he replies softly.

The legacy

45 years on, Cevert and his mere three and a half seasons in the sport still resonate down the years, both for Stewart, his family and for Formula 1 fans around the world (in 2013, Toro Rosso’s Jean-Eric Vergne even wore Cevert’s helmet colours at that year’s Monaco Grand Prix).

The chief reason likely centres around Cevert’s extraordinary good looks, the potential of his talent and his youth, all seen in the context of the violence of the accident that killed him – and which turned him, in the process, into a kind of James Dean of Formula 1. But another big part can probably be ascribed to a Cevert quality that is never far from cropping up when people talk about him. As Stewart says: “He just was such a charming person."

An example. A week before he died, Jackie and Helen Stewart invited Cevert to join them on holiday. Staying in a Bermudan hotel patronised by a decidedly geriatric set – “we were the only young people there,” remembers Stewart – Cevert set about winning over the elderly clientele with his remarkable musical talent.

“There was a cover over the grand piano,” remembers Stewart. “He took the cover off and then sat down and played. He was a very good classical pianist, and he played Beethoven's Pathetique. And I’ll tell you what, these people were just out of this world – because none of them were getting much out of the night! [Laughs] And suddenly, every single night, he would get up and play the piano… The grannies were all over the place!”

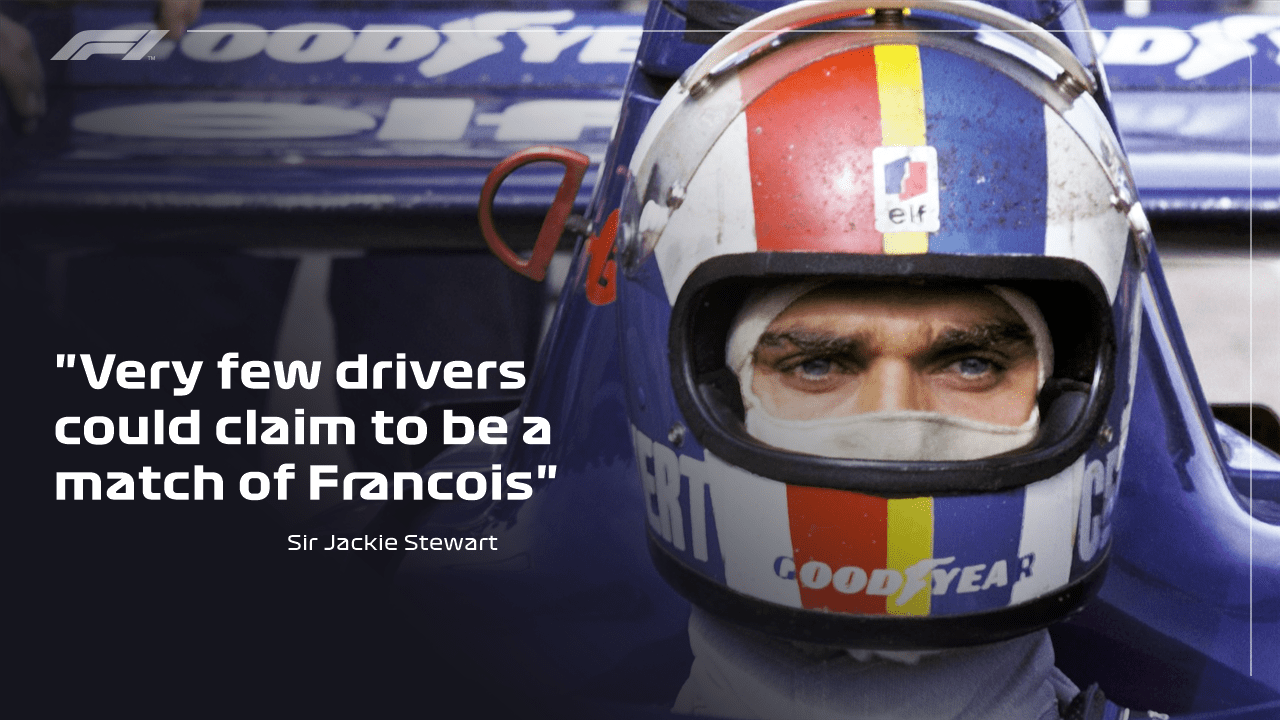

So does the man who perhaps knew him best, who nurtured his talent and shared his every racing secret with him, think that Francois Cevert stands up in that role as the greatest single embodiment of the archetypal F1 driver?

“Very few racing drivers could ever claim to be a match of Francois Cevert,” says Stewart, who still keeps several pictures of his friend around the house. “I don't think there's anybody who's ever been a match to Francois Cevert. In every element: his manners, his presentation skills, his good looks, his driving skills.

“He became a great friend of the whole family. He stayed with us quite a lot, we travelled together a lot and we were just awfully good friends. And I think that kind of thing probably is quite rare.”

And the final, burning question. Just how good was Francois Cevert, the driver, once Stewart had finished with him?

“I think I brought him from what might have been considered to be just another driver into somebody who I think would have gone on to win the world championship,” says Stewart, “of which, I would have been very proud.”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked F1 ICONS: MotoGP legend Casey Stoner on the ‘freaking phenomenally talented drivers’ who have inspired him

News 'It's impressive and exciting' – Team principals laud F1's motorsport ladder for preparing rookies

TechnicalF1 Unlocked TECH WEEKLY: How McLaren are making the difference in F1’s intriguing 2025 aerodynamic race

News Vasseur calls for Ferrari to be more ‘consistent’ as he highlights where team needs to improve