How the Renault R25 finally ended Ferrari's dominance and delivered Alonso's first title

With Fernando Alonso’s name back in the headlines as Renault seek a replacement for McLaren-bound Daniel Ricciardo in 2021, Mark Hughes looks back at the car that delivered him his first drivers’ championship in 2005 – the Renault R25 – and Renault their first-ever constructors’ title. Featuring illustrations from Giorgio Piola, here’s the technical guide to how the R25 shook up the order and pulled off a near-flawless season.

It was the final year of the three-litre V10 formula but, although the engine technical regulations were unchanged in 2005, not much else was.

New aerodynamic restrictions applied to the front and rear of the cars and a new sporting regulation – which lasted only for this season – stipulated no tyre changes during the race.

READ MORE: Alonso? Vettel? Who is really on Renault's driver shopping list for 2021?

The pit stops were therefore planned solely for refuelling, which wouldn’t be banned until 2010. In addition, there was a late-notice requirement that each engine should last not one weekend, as in 2004, but two.

The aerodynamic regulation reset probably helped Renault by wiping out much of the accumulated advantage built up by the dominant Ferrari team in the immediately preceding seasons.

However, the banning of tyre changes was a far more powerful factor in that it rendered Ferrari’s Bridgestone tyres uncompetitive against the grippier and longer-lasting Michelins used by most of the other teams, including Renault.

As a result, Ferrari were barely contenders in ’05 and Alonso’s main competition would come from the McLaren-Mercedes MP4-20 of Kimi Raikkonen.

READ MORE: How Niki Lauda's final title-winning car, the 1984 McLaren MP4/2, changed F1

The R25 represented the fifth year of a technical theme initiated by the team in 2001, initially based around a very wide vee angle engine, conceived to lower the car’s centre of gravity and confer an aerodynamic advantage.

Although that engine proved uncompetitive, it set Renault on a technical path that saw them progress up the grid each year, and which culminated in Alonso’s 2005 and ’06 titles.

The wide-angle engine had proved so afflicted by vibration in 2001 that its maximum revs were restricted and its components were beefed up to withstand the strain, which gave the car rearward-biased weight distribution.

This unintended consequence brought great traction benefits, especially when allied to a Michelin tyre that had a very flexible sidewall. The rev restriction led the engine department to develop a fatter torque curve instead – which led to great driveability and fuel economy.

READ MORE: Ricciardo reveals the two races that earned him ‘respect’ from Schumacher and Alonso

The lower revs also meant fewer cooling requirements. While these benefits were not enough to fully overcome the engine’s power shortfall, they sent the chassis and aero teams down very productive development paths that were at odds with those being pursued elsewhere.

So even when the 2004 car finally ditched the wide-angle V10 and opted for the narrowest vee angle in the field, at 72-degrees, the car deliberately carried more of its weight on the rear axle than any of its rivals and continued to be tuned to give the maximum area beneath the torque curve.

That 2004 motor was essentially just an updated version of the 1990s unit that had powered Williams-Renault to glory. For 2005 an all-new version of the 72-deg engine was conceived instead, by the Viry engine department headed by Rob White, with project management by Axel Plasse.

This one had been totally repackaged for a lower centre of gravity, a much stiffer installation, more tightly-packaged components and lower weight. It delivered around 800bhp at 19,000rpm, slightly less than the Mercedes but needing less fuel (allowing a tank capacity of 98kg compared to the McLaren’s 106kg) and cooling.

READ MORE: Alonso to Renault in 2021 is a 'no-brainer' says McLaren boss

Progress in electronics was rapid at this time and the all-new electronic brain integrating chassis and engine – the Step 11 – was not only much lighter than that in the previous year’s car but featured four times the processing power and 10-times the data acquisition capacity.

The chassis team was led by Bob Bell, with Tim Densham as chief designer and the aerodynamics led by Dino Toso. An integral part of the philosophy of this car was to create huge rear stiffness across the back for maximum stability. The narrow-angle engine was part of this.

Compared to the more commonplace 90-degree engines used by the rest of the field, the lateral stiffness of the engine-chassis installation with a narrow-angle vee will be greater for a less than proportional penalty in vertical stiffness. The stiffness of the engine itself – regardless of the installation – will also be better.

Two carbon fibre struts linked the front of the gearbox to the chassis behind the cockpit to further enhance rigidity. The gearbox is a crucial part in giving the required structural stiffness and the R25’s very strong titanium gearbox casing was long and relatively heavy, giving the desired rearwards-biased weight distribution.

READ MORE: Watch Alonso’s superb 2012 European Grand Prix win in full

Most F1 cars of the time were trying to get the weight as far forwards as possible and by 2005 were able to get to around 47/53% front/rear. Renault preferred a split of around 42/58%, ie with 5% more of the car’s total weight on the rear axle than rival designs.

That helped retain the fantastic traction that had been part of the previous wide-angled cars’ strength. The long gearbox was responsible for the car having the longest wheelbase of all the 2005 cars (which would also help with the rearwards weight distribution), which in turn created more downforce-generating underbody area.

The engine’s friendly torque curve gave it great driveability which, together with the fantastic traction, ensured rocket-like getaways off the line and great slow-corner performance. That torque curve also allowed the gearbox to have only six speeds at a time when everyone else felt the need for seven.

The unusual weight distribution and massive structural stiffness at the rear endowed the car with quite a distinct handling trait. It would tend to understeer, the lightly-loaded front tyres taking longer to load up than a more forwards-heavy car. But once loaded up, they could generate more grip for a given level of load.

So, to speed up the slow-building of the front tyres’ grip into slow corners where a lot of steering lock is needed, Alonso would typically be hugely aggressive with his steering input.

This would get him as early as possible to the point where the car’s great traction could be utilised. Giancarlo Fisichella's more classical style in the team’s other car would see him unable to get the car loaded up as quickly and therefore later on the power.

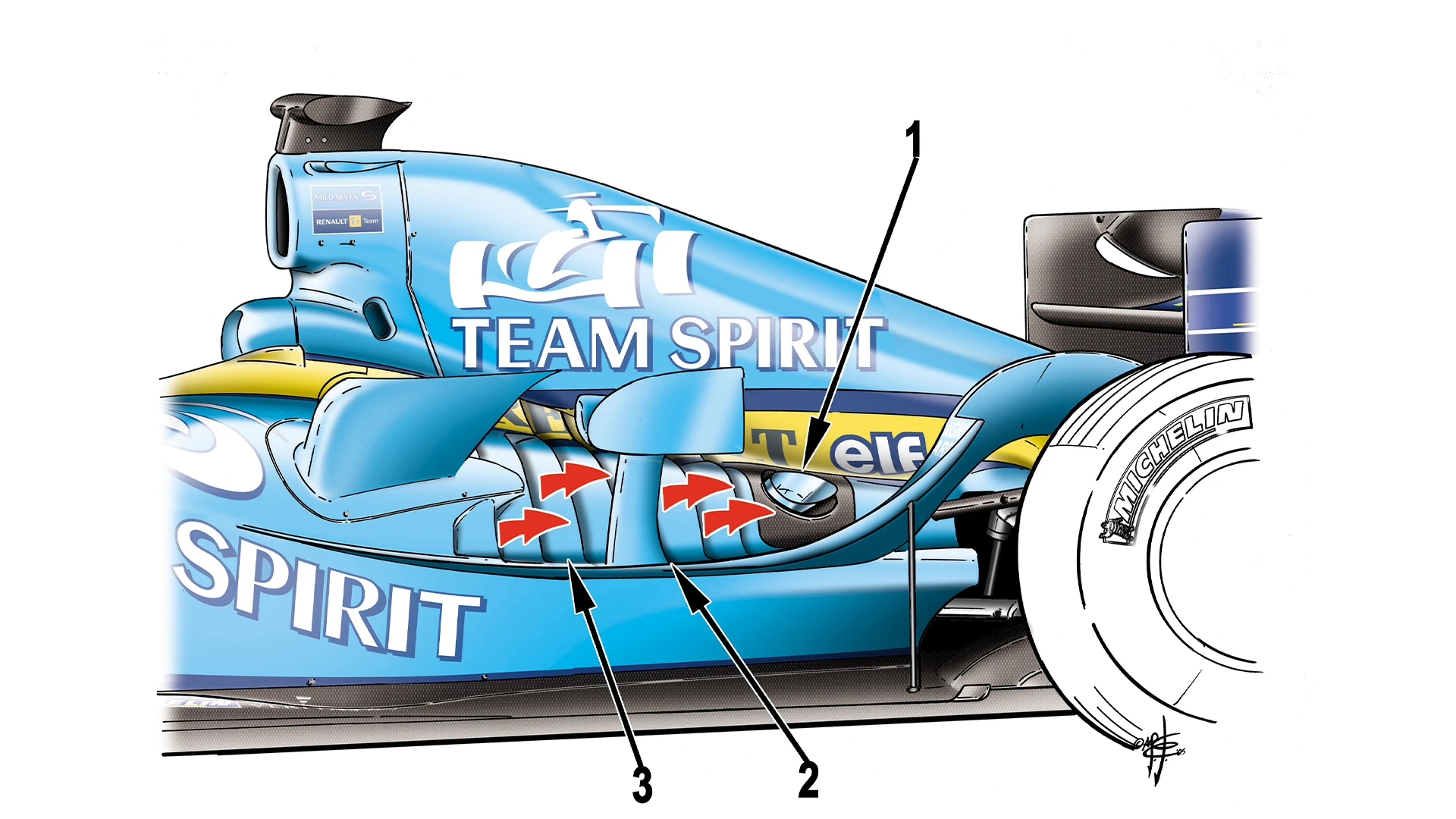

In general, the weight distribution of a car needs to be well matched-up to its front/rear aero balance. The R25 had relatively simple front wing and brake ducts at a time when others, notably McLaren, were beginning to contour these components extensively.

The chord area of the front wing was not to the maximum permitted and it was a relatively simple twin-plane/single-slot gap design. This was all driven by the need to derive a greater proportion of the car’s downforce from the rear.

Not all the available airflow at the front of the car was being used to create downforce from the front wing and ‘flow conditioners’ – ear-like extensions sprouting out from the top of the nose - were sometimes used to direct more of the flow to the rear of the car.

READ MORE: How Mercedes' 2020 car tackles the W10's biggest weakness

The regulation front-wing span was much narrower than today’s, the wing barely overlapping with the inside edges of the tyre. This meant the focus of airflow was inboard, maximising flow to the floor past the bargeboards. Outwash airflow only really became a big area of attention with the wider front wings introduced in the 2009 regs.

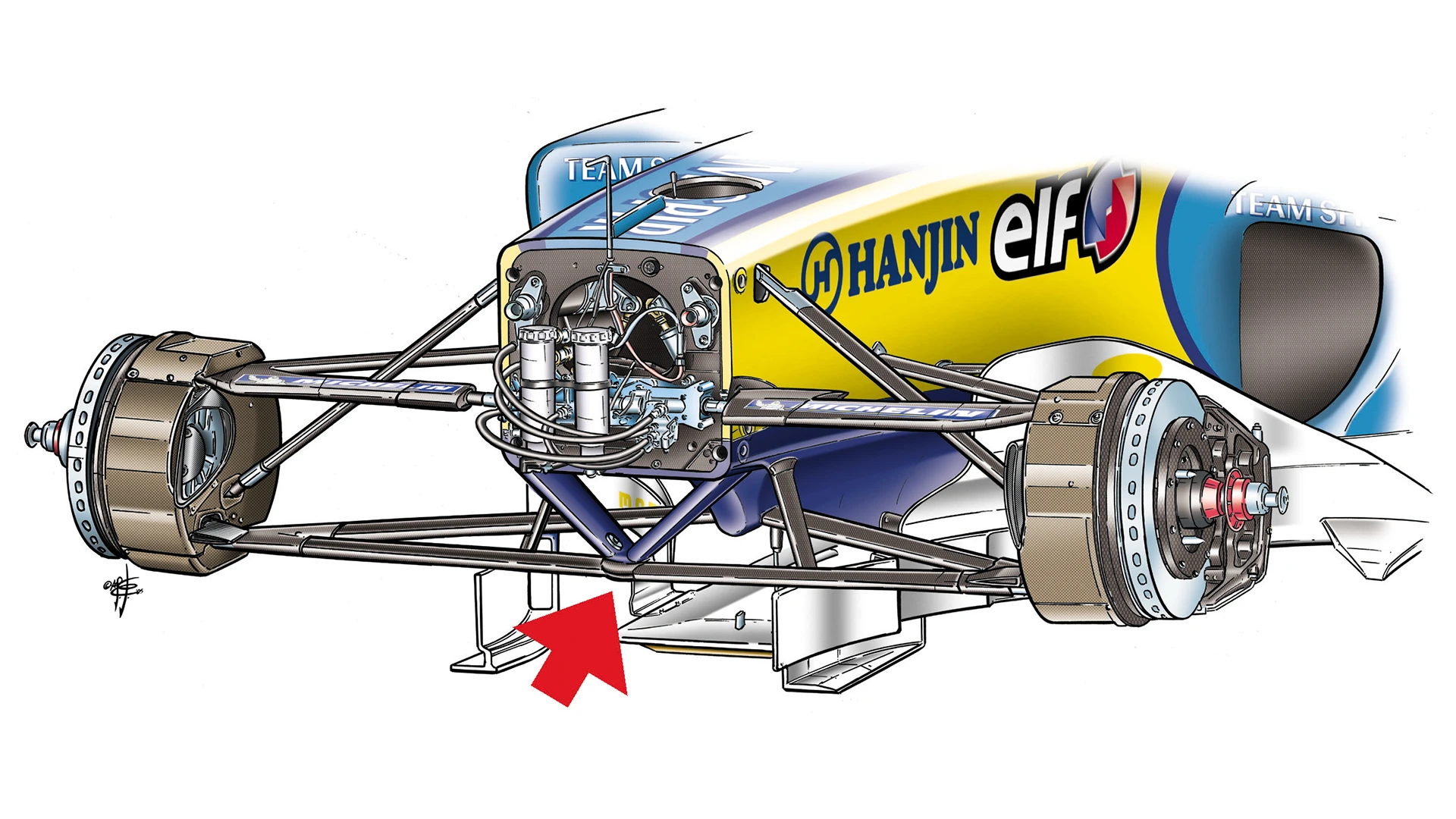

Because of this preoccupation with maximising the flow to the underfloor, there was an ongoing search for the least aerodynamically disruptive front suspension mounting point at the inboard end. For years, the standard method had been to mount the lower wishbones on each side to a central ‘keel’ in that part of the monocoque.

But, in 2001, Sauber had introduced the ‘twin keel’ whereby two smaller keels, one on each side, kept more of the central part of the under-nose unobstructed. It was aerodynamically better but structurally compromised.

Nonetheless, it became very fashionable until McLaren lowered the height of their chassis and raised the inboard wishbone mounts until they met up, so not needing any keel at all. The zero keel was very effective aerodynamically but brought limitations to the suspension geometry.

READ MORE: Have Mercedes changed the game with DAS?

With the R25 model, Renault introduced their own unique take on things with the v-keel (as seen in the image above). Renault’s technical director, Bob Bell, summarised it as follows: “We believe the v-keel is a very elegant solution to this dilemma, as it combines the virtues of both systems: we have obtained an aerodynamic advantage for minimal structural penalty, while maintaining our preferred mechanical configuration for the front suspension.”

The new aero regulations for 2005 stipulated that the outboard area of the front wing be raised by 50mm, taking it out of ground effect and therefore making it less effective. At the rear, the outer channels of the diffuser had a newly-defined maximum height.

This, together with the elimination of the rear tyre/floor seal – there had to be a free space of defined dimensions in the floor ahead of the rear tyre, thereby breaking the aerodynamic seal of the floor – reduced rear downforce by as much as 10% compared to the previous year.

As the car developed and the team noted that its rear tyre usage was a little too heavy, so they found themselves needing to be less extreme in the rearward bias.

READ Grosjean reveals how his ex-team mates Raikkonen and Alonso are ‘surprisingly’ similar

So as the ballast was moved forwards, the aero balance needed to match and the front wings sported outboard upper winglets from Imola onwards. These gave the extra downforce required without fundamentally changing the flow pattern of the air being fed to the bargeboards and bodywork further back.

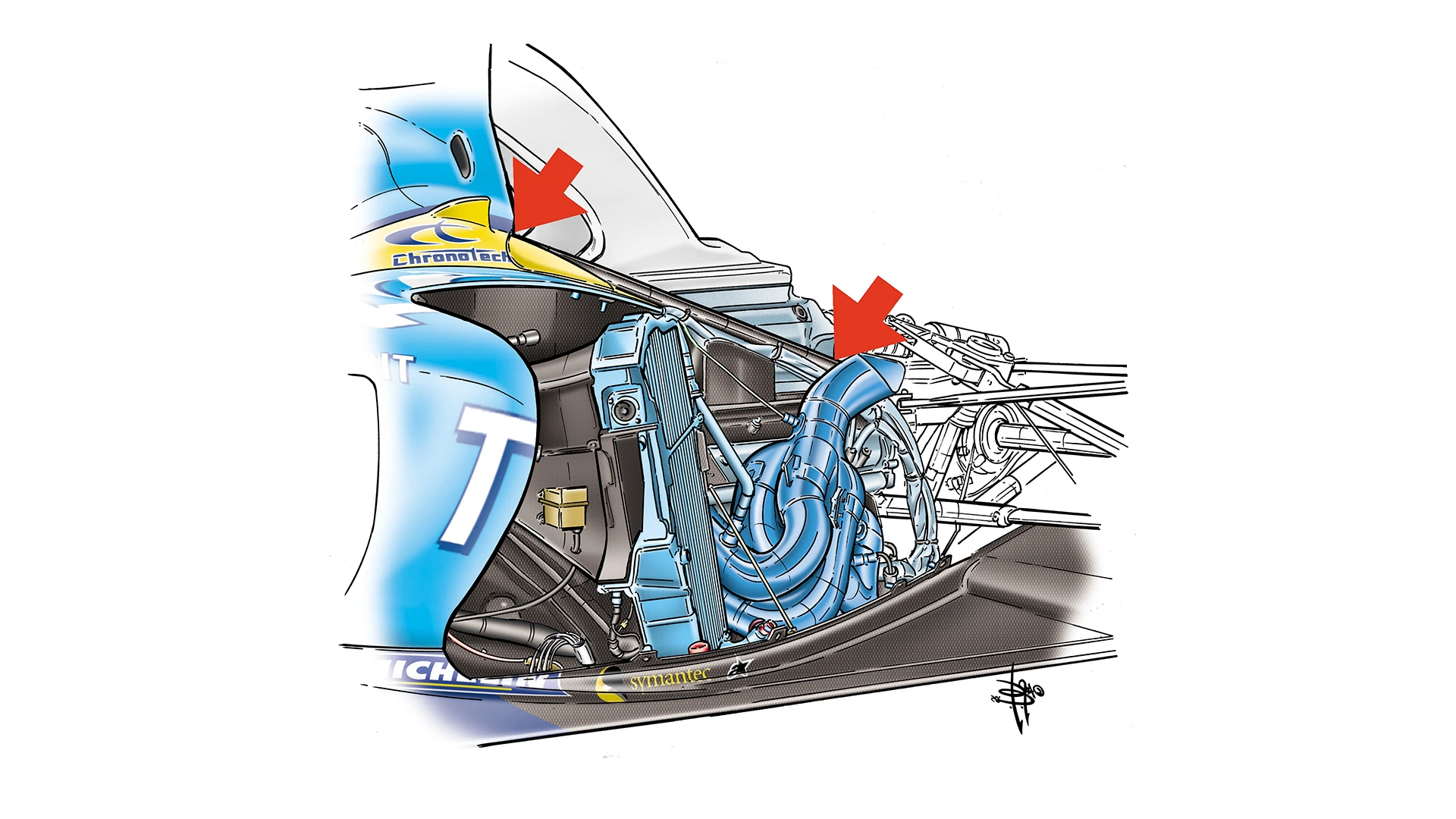

The bodywork was notable for the extreme use of louvres for cooling exits. The whole rear upper surface of the sidepods was latticed with these louvres whereas other teams of the time preferred to use chimneys which are more powerful but prone to the airflow reversing its direction.

The louvres encourage a gentler progression for the warm air exiting from the radiators and the attachment therefore tended to be better.

Although the 2005 McLaren was generally an outright faster machine, the R25 was fantastically reliable and, in Alonso’s hands, fast enough to mount a near-perfect championship campaign.

The Spaniard repeated the feat in 2006 with the updated R26 – but spent the next 12 years seeking a third title. Now, all eyes are on Alonso to see if he will make an incredible return to Formula 1.

READ MORE: Alonso? Vettel? Who is really on Renault's driver shopping list for 2021?

More TECH TUESDAYS

What does the 2021 aero rules change mean for the cars – and which teams will it hurt most?

The hidden upside of Mercedes and Alfa's DRS-boosting rear wing

Under the bodywork of the Ferrari 312B3 on the anniversary of Niki Lauda's first F1 win

Under the bodywork of the Alfa Romeo ‘Alfetta’ – 70 years after it won the first ever F1 race

Under the skin of Schumacher's first Ferrari winner

Next Up

Related Articles

VOTE: Who has the best driver line-up for 2026?

VOTE: Who has the best driver line-up for 2026?.webp) ExclusiveLowdon on why Zhou ‘ticked all the boxes’ for Cadillac

ExclusiveLowdon on why Zhou ‘ticked all the boxes’ for Cadillac F1 drivers who bounced back after dropping off the grid

F1 drivers who bounced back after dropping off the grid.webp) What F1 drivers have been up to over the festive holidays

What F1 drivers have been up to over the festive holidays Williams become latest team to announce 2026 livery reveal date

Williams become latest team to announce 2026 livery reveal date F1 Arcade announces opening date for new Atlanta venue

F1 Arcade announces opening date for new Atlanta venue