Feature

JIM CLARK - What made him so good?

Share

The Saturday of the Bahrain Grand Prix earlier this month marked 50 years since Jim Clark – one of F1’s greatest ever champions – was killed in an F2 crash at Hockenheim. For Formula1.com contributor David Tremayne and many others, the Scot remains the greatest driver to have ever pulled on a helmet and climbed into a racing car. But all these years later, why does he continue to be so revered? Via an extract from DT’s new book - a 20-year labour of love entitled ‘Jim Clark: The best of the best’ – we offer a glimpse into the talent of a man Fangio once called “outstandingly the greatest Grand Prix driver of all time”…

As a driver he was the rare breed who didn’t need his entire range of mental faculties just to drive fast. Like all of the great champions, much of that was automatic and there was always plenty left over for the unexpected. The way he dealt with Innes Ireland’s intransigence at Monza in 1963 [when his former team mate had deliberately blocked him for several laps before Clark ingeniously worked his way past] was a case in point.

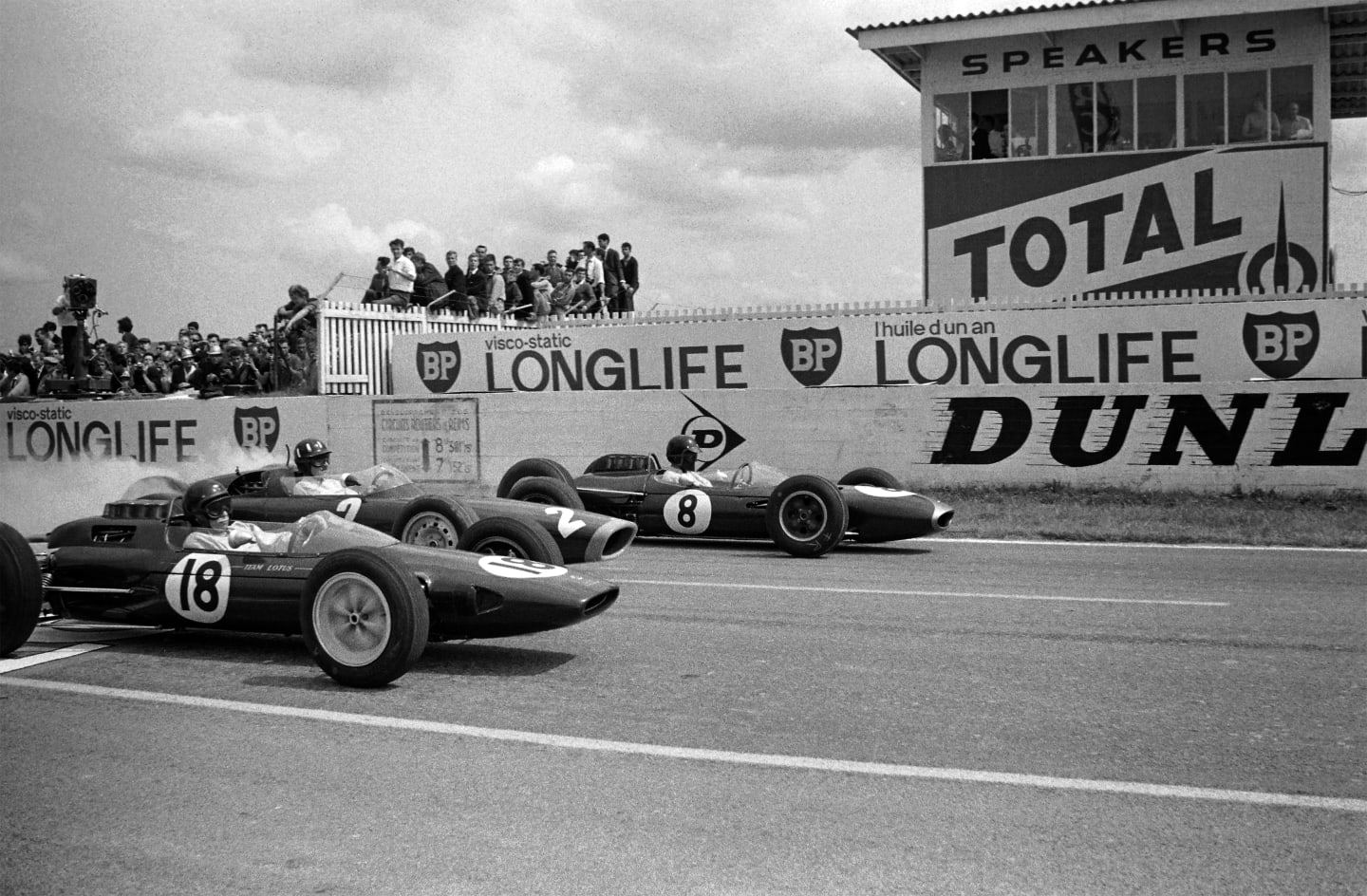

Jack Brabham’s picture of Jim before the start of a race suggests that at those moments Jim was anything but calm.

"The silly thing was that he was an absolute bundle of nerves," Jack said. "Just before the start of a race if you went up and gave him a push, it frightened the hell out of him. And, of course, I didn’t help. When I was on the front row with him, just before the start, I’d point at his rear tyre! Eventually he ignored that.

"We had a doctor at Monaco once going around and taking pulses and blood pressures before the start of the race, and he didn’t want to let Jimmy start. He reckoned Jimmy was in such a state that he shouldn’t start! But once the flag dropped, it was different altogether."

Jim, meanwhile, told a different story when asked the secret of his great starts, and claimed that part of his technique was just to throw a hard stare across at the drivers alongside him, "then get myself madder than hell and take off!"

I'd get myself madder than hell and take off!

Clark on his race start technique

He provided further interesting insights in his biography Jim Clark At The Wheel.

"The supreme attraction of motor racing to me is driving a car as near the physical limit as possible without stepping over it.

"I have always recognised and respected the safety limits for myself and other drivers, and I would far rather lose a race any day than overstep myself or my car.’

But he said of fear, "It’s all part of it. If there was nothing to be frightened of, any silly bugger could get in the motor car.

"I do think of the danger, from time to time. Especially when there are a lot of trees about." And, with poignant prescience, he added: "If you do go off, you’re gonna hit them, hard.

"The man with natural ability uses finer limits than the man who has none. It is like a born artist being able to place paint on a canvas and make it a picture, whereas the majority of us would only make a mess. For I consider motor racing an art."

He placed a big premium on braking, which he regarded as the most important thing you could learn in racing.

"It comes as a great shock to find that you can brake much later than you ever thought was possible. And all through racing in its every form braking is more important than most people think. It is considered that leaving your braking to the very last minute is important and I would agree; but I would also say that where you take the brakes off again also matters. It depends very much on how the car you’re driving handles.

He was able to drive an understeering car in a four-wheel drift and judge the exits to perfection

Peter Collins

"Often, if I want to go through a given corner quicker I don’t necessarily put the brakes on any later than usual, but I might not put them on very hard, and take them off earlier. Where you are led into the trap is leaving your braking too late and having to run deep into the corner and brake at the last moment, you might certainly arrive at the corner quicker, but there is a psychological tendency to brake much harder than you need to and therefore overbrake."

Analysing the Clark technique, Peter Collins [former team manager at Team Lotus and Williams, and an avid Clark fan], who knows more about what makes great drivers than most, made some key observations.

"The old Nurburgring was a JC favourite, supremely challenging and dangerous.

"Lotuses were generally considered to understeer, which was something that many drivers had trouble dealing with. Traditional wisdom says that the oversteering F1 car is the faster one, but whether by default or intent, Jimmy found a way to turn the understeer into a positive. His driving at the Nurburgring in 1964, for example, demonstrated a significant difference to that of John Surtees, Dan Gurney and Graham Hill and other drivers at that time.

"To overcome that understeer, which should in reality have been a handicap that limited entry speed, he appeared to make a very assertive first steering input which momentarily destabilised the rear of the car, allowing the shift of rearward weight to influence the attitude of the car. This rotated the mass of the car more effectively than the steering could because of the inherent understeer. At the same time, it set the mass on a trajectory to achieve the desired line and exit position.

"Once the weight was rotated as the back momentarily stepped out, the car then returned to its traditional handling characteristic which allowed him to floor the throttle. This in turn allowed him to maintain a higher entry speed and cornering speed and the understeer allowed him to get back on the power earlier than his opponents without any fear of power oversteer. He was able to drive an understeering car in a four-wheel drift and judge the exits to perfection. This would have been particularly effective with the 1½-litre cars which had relatively low power and torque.

The supreme attraction of motor racing to me is driving a car as near the physical limit as possible without stepping over it

Jim Clark

"He also made great use of stabbing at the throttle mid-corner, which adds to the belief that he was trying to make the back move to steer the car more as required.

"His throttle blips were not as frantic or aggressive as Keke Rosberg’s or Ayrton Senna’s in later years, but they were definitely part of his bag of tricks.

"Apart from these special techniques that he applied, his driving was incredibly fluid even in dramatic moments. Watching the first laps of various races you got a very strong impression that he was mentally more ahead of the car than was the opposition.

"Watching him leading at the ’Ring in 1967, for instance, the impressive thing was that there were no dead moments in transition from braking to turn-in, to throttle on. The differences compared to Dan Gurney and Denny Hulme were small, almost imperceptible, but made a big difference even in a car that was struggling from early on with a deflating front tyre.

"The more you look at videos, the more his structure, discipline and consistency (turn-in, apex, exit points) become obvious, together with their significance and value. His lines are more efficient; shallower entry lines, tighter lines, less track and more rotation. Gurney and Hulme were not quite as precise or consistent with their lines then, nor were Surtees, Gurney and Hill back in 1964.

"Jimmy’s disciplined driving structure most likely played a big part in his performances. The more you do the same thing, the more it becomes habitual and repeatable. This is a big problem today with young drivers.

"With a lot of pushing, the more consistent their structure becomes and the faster they go without actually trying any harder. Constantly varying lines means that the available grip provides no reference to the previous lap. Being off line by 12 inches puts the outside tyres on a dustier/dirtier part of track.

His driving was incredibly fluid, even in dramatic moments

Peter Collins

"Discipline is something that is ingrained as we grow and it’s likely that the exigencies of Jim’s early farm life would have instilled a natural sense of discipline within him.

"His starts were nearly always exceptional. Watching the start of various German Grands Prix, where the four-car front line always provided a good comparison view and perspective, suggests that he either had a lower first gear than most, or was much quicker in his upshifts, as he nearly always gained metres when everyone else grabbed second. He always lit up the rear tyres and didn’t seem to try to limit the wheelspin.

"Apart from the incredible starts, his first laps were just so impressive. His entry speed to a first corner was visibly higher, which displayed an amazing belief in himself and an incredible awareness of the absolute grip limit available at that time, when others were still finding their limits.

"That is particularly relevant when you consider that at the first corner the tyres were cold. Somehow, he must have been able to get some perception of the available grip, whether visually, by gauging traction off the grid, or grip under the brakes. Whatever it was, he obviously processed all the information very quickly and then relied on his judgement.

"Jimmy was an absolute artist and a joy to watch. Whether watching him drive first-hand in 1965 and 1966 in the Tasman Series or on video, it was - is - just mesmeric, exciting and breathtaking. The Nurburgring commentator’s voice and reaction to his speed into and through Brunnchen, in one particular video, exemplifies that. Nothing has changed in that respect since seeing him race at Warwick Farm in 1965 and watching videos today.

"As an aside, it is also interesting in the 1964 German Grand Prix video to note that he was the last driver to get into his car. All the other drivers had been in their cars for at least a minute. From the time he was installed in the Lotus 33’s cockpit to the flag dropping was just under another minute and a half. Perhaps this was a way for him to keep his nerves in check before the start, when the indecisive Clark outside the car turned into the superman Clark in the cockpit.

"Nobody compares drivers as complete packages, but they should. Jimmy was velvety, silky smooth, and watching him was like watching a ballerina dance. He made driving a race car an art form. I never saw anyone better."

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked 5 Winners and 5 Losers from Saudi Arabia – Who leaves Jeddah the happiest and who has work to do?

News ‘I’m 2000% behind him’ – Vasseur backs Hamilton amid early Ferrari struggles as he insists ‘potential is there’

News Alonso says Aston Martin ‘need to get used to’ not scoring in 2025 as he reflects on dramatic near-miss with protégé Bortoleto in Jeddah

TechnicalF1 Unlocked TECH WEEKLY: How McLaren are making the difference in F1’s intriguing 2025 aerodynamic race