Technical

Re-writing the F1 rulebook - Part 2: from driver aids to increased safety

Share

The 2017 season sees arguably the biggest technical shake-up in F1 racing for 20 years, with the rule makers adopting a previously unseen approach of changing the regulations to raise speeds rather than keep them in check. To mark this dramatic rules shift, we’re looking back over the other occasions in the modern era when F1 designers were forced into a fundamental re-think, with our next focus on the early nineties…

As the eighties gave way to the nineties, F1 cars had become increasingly high-tech, with the leading teams having developed all manner of electronic technology to improve performance, including active suspension, traction control, anti-lock brakes and launch control (not to mention other exotic technologies, such as such as Continuously Variable Transmission and four-wheel steering that were tested but never raced). But in a bid to curb spending and counteract criticism that drivers were becoming an ever smaller part of the performance equation, the FIA announced midway through 1993 (pictured above) that all so-called ‘driver aids’ - save for semi-automatic gearboxes - would be banned for 1994. In-race refueling (pictured below) would also return for the first time since 1983 - another decision that would impact upon car design.

Three-time world champion Ayrton Senna was one of those who had been vocal about the need to ban driver aids, but the great Brazilian would sadly be killed in an accident during the third race of the new era at Imola. "The cars are very fast and difficult to drive,” Senna had said prophetically after testing his now gizmo-free car during pre-season testing. “It's going to be a season with lots of accidents and I'll risk saying we'll be lucky if something really serious doesn't happen..." Senna’s tragic passing (and the death of Roland Ratzenberger, killed that same Imola weekend) ushered in a number of sweeping changes to car design to reduce performance and improve safety.

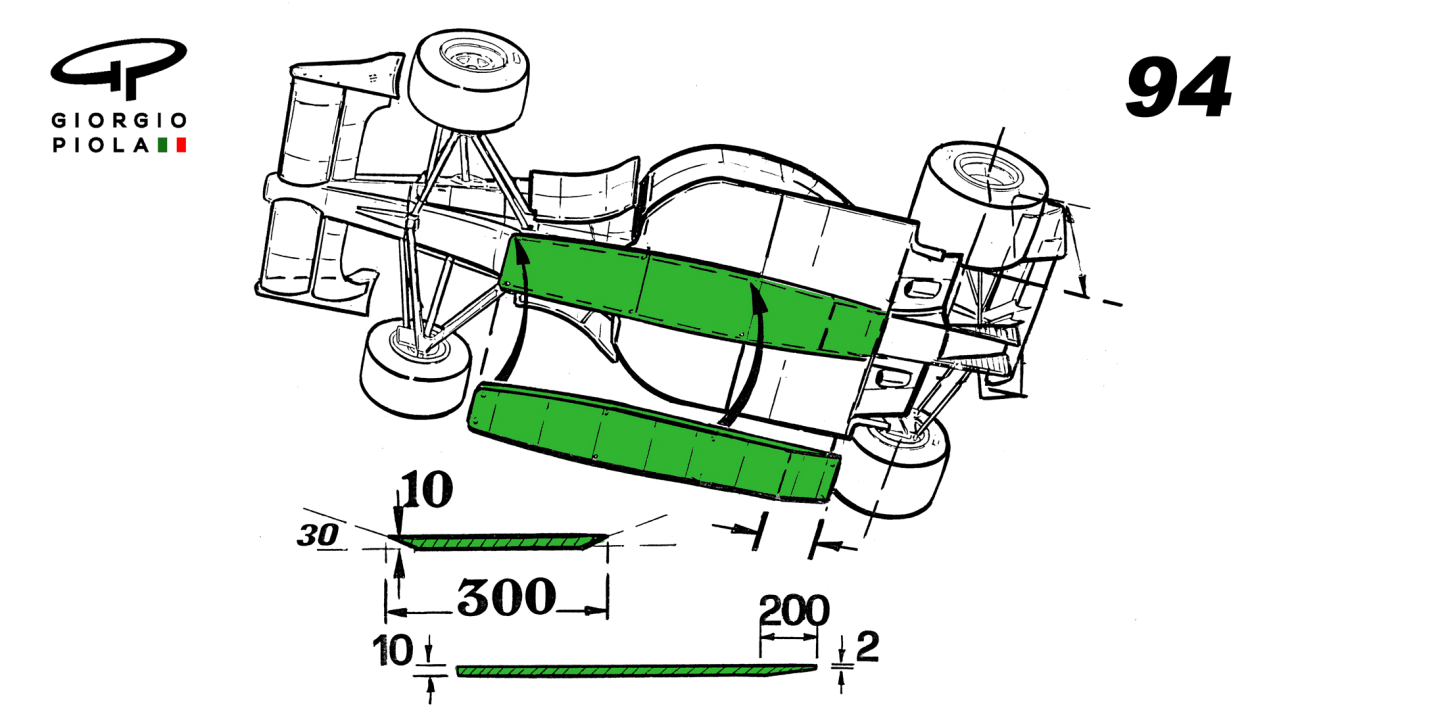

In the five-race span between the Spanish and German Grands Prix, a number of steps were put in place, including new restrictions to dimensions of the front wing, rear wing, turning vanes and diffuser, changes to the airbox to reduce engine power, and the introduction of a 10mm wooden plank (pictured above and below) on the flat-bottomed underside of every car.

This plank, which remains in place to this day, prevented teams from running ultra-low ride heights because only 1mm of wear was permitted at the end of each race. Benetton famously fell foul of this rule at the Belgian round when post-race checks on Michael Schumacher’s car showed excess wear. This had been caused, the German’s team argued, by a mid-race spin over a kerb, but their appeal was rejected and chief title rival Damon Hill was awarded the win.

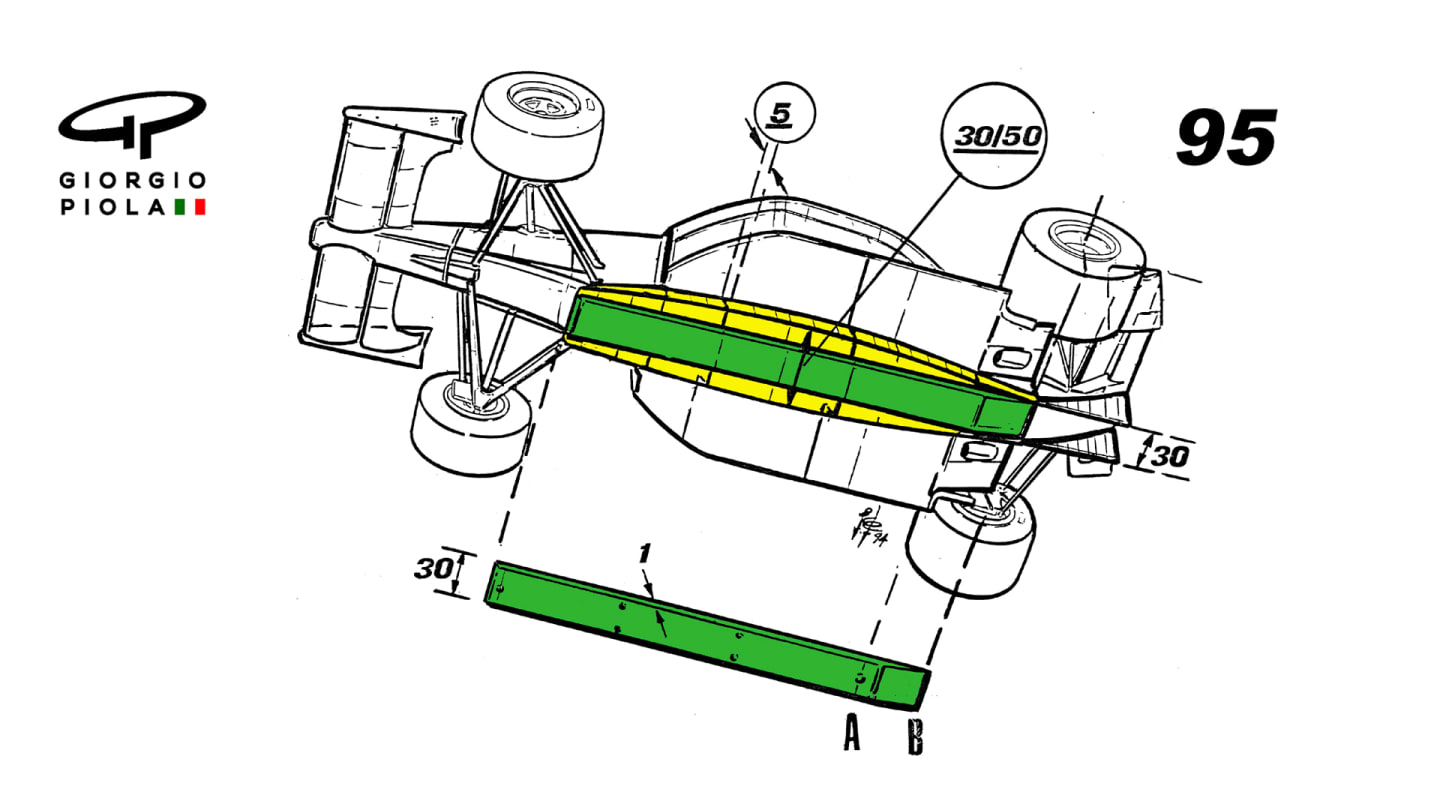

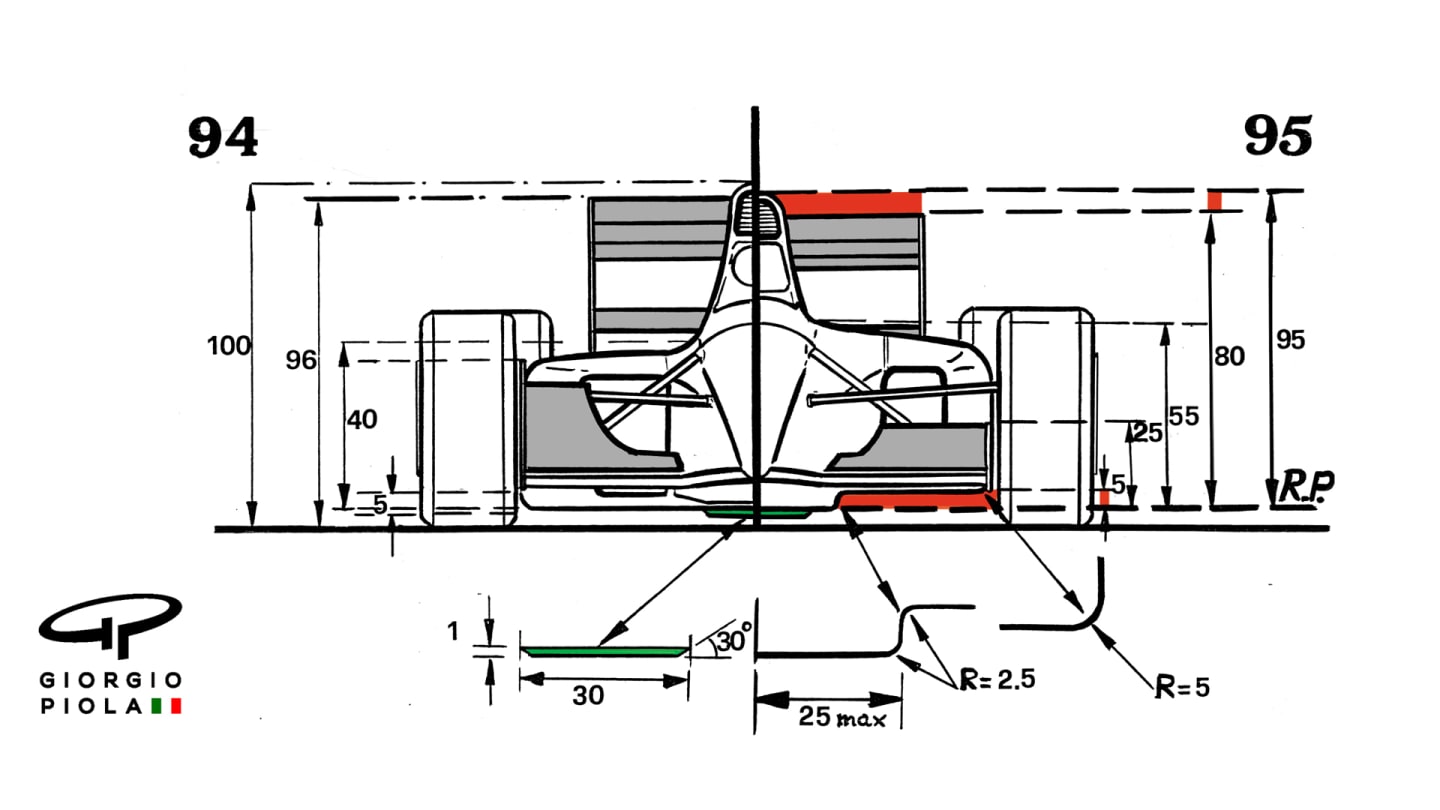

From the Japanese Grand Prix teams were allowed to put 10 titanium skid blocks on the floors of their cars to protect the plank, but a much more significant change to chassis undersides was on the way for 1995 - the stepped flat bottom (pictured above). The introduction of the step saw either side of the central section of floor raised by 25mm - a move which was estimated to reduce the amount of downforce generated by the car’s underside by as much as 50 percent.

Further aerodynamic reductions for ‘95 (pictured above) were made by reducing the height of the rear wing (by 100mm) and reducing front wing endplate height (to between 5cm and 25cm above the flat bottom) and length (must not extend further back than 35cm in front of the front wheel axis). A reduction in engine capacity from 3.5 to 3.0 litres slowed cars further.

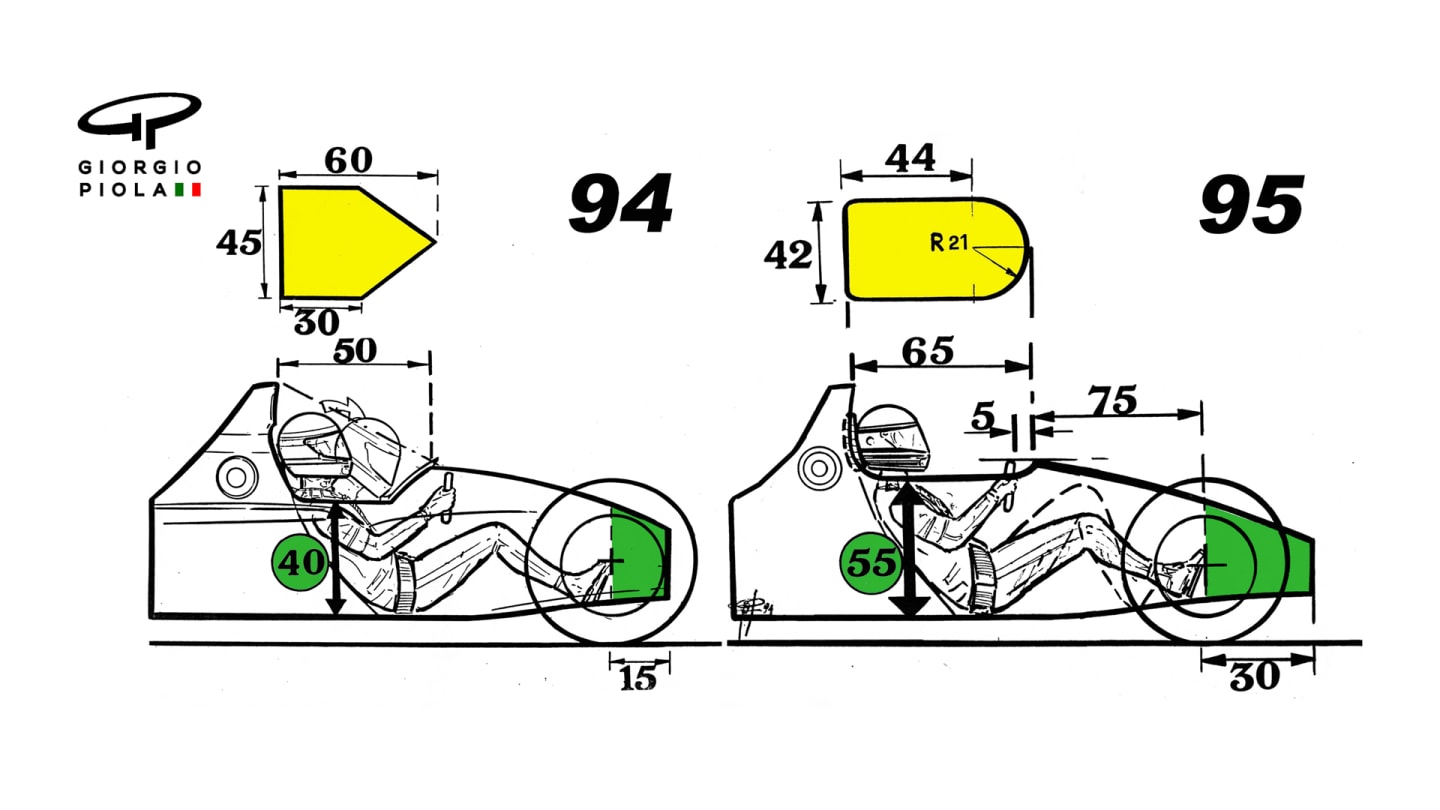

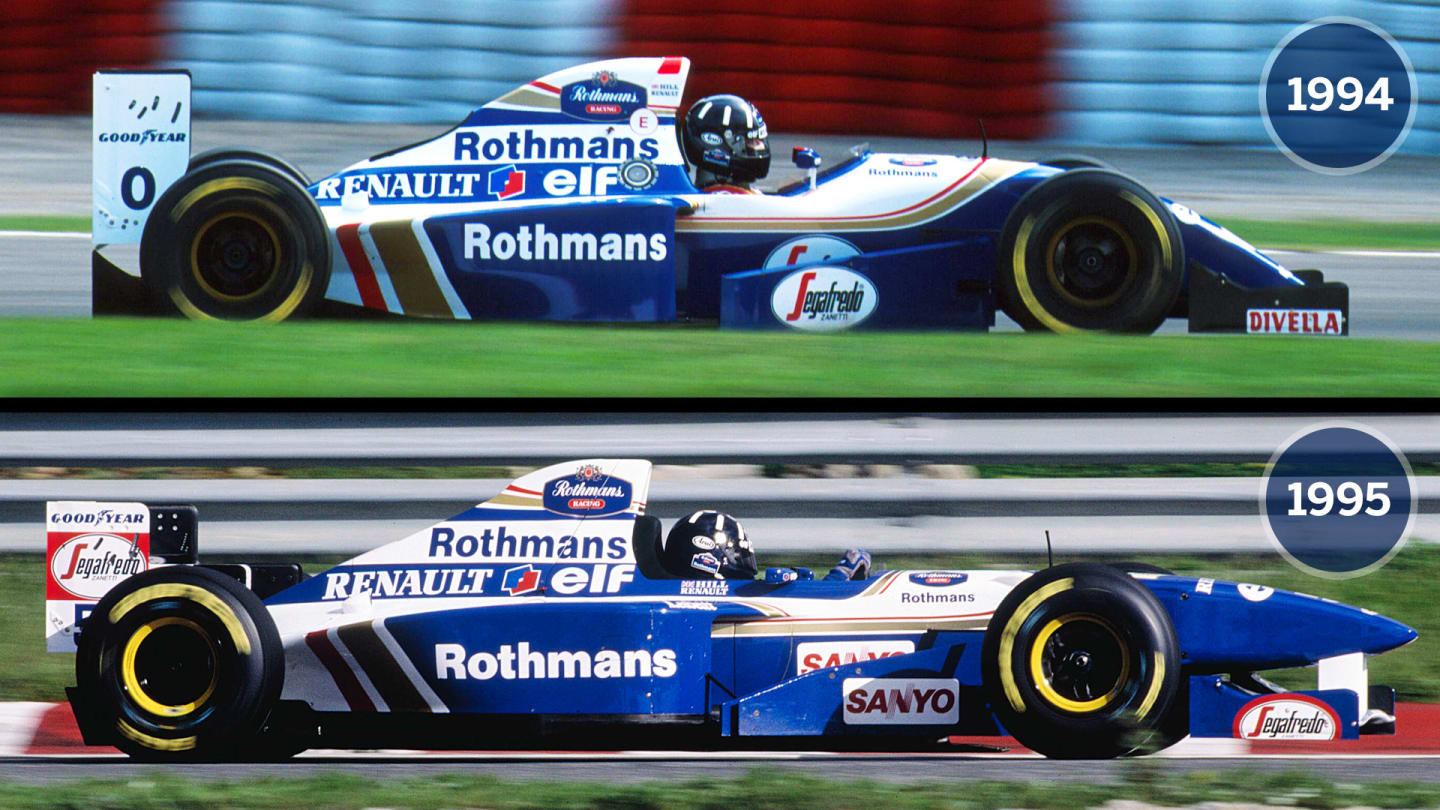

Meanwhile, on the safety side there were some of the biggest steps forward ever seen from one season to the next. The cockpit opening was increased in length to limit the possibility of forward impacts with bodywork, while the width was narrowed slightly and the cockpit sides raised to cover the drivers’ shoulders. The chassis was also required to extend 300mm (rather than 150mm) in front of the drivers’ feet and be able to withstand more force (the frontal impact test speed increased from 11 to 12m/s , while the load in the nose push-off test increased by 33 percent). A survival cell side impact test was also introduced. The changes resulted in a car that looked markedly different from its predecessor - especially in terms of the 'amount' of driver visible in the cockpit (see picture below).

The teams had had to work extremely hard, but F1 cars were now safer than ever before - and over the next few years they’d get even safer still.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

FeatureF1 Unlocked 5 Winners and 5 Losers from Saudi Arabia – Who leaves Jeddah the happiest and who has work to do?

News Horner repeats message over Verstappen’s future as he stresses ‘we win and we lose together’

News Vasseur calls for Ferrari to be more ‘consistent’ as he highlights where team needs to improve

News Bayer admits Lawson left ‘sad and puzzled' by Red Bull seat swap as he predicts New Zealand driver 'will be back and he will be quick'